Scientific, Industrial, and Cultural Heritage: A Shared Approach

The Information Society Technologies programme within the EU's Framework Programme Five supports access to, and preservation of, digital cultural content. This document describes some common concerns of libraries, archival institutions and museums as they work together to address the issues the Programme raises. This accounts for three major emphases in the document. First, discussion is very much about what brings these organisations together, rather than about what separates them. Second, it describes an area within which a research agenda can be identified; its purpose is not to propose a programme of work or actions, rather a framework within such a programme might be developed. Finally, although the main focus is on access to resources, this is placed in an overall life-cycle context.

Broad Goals

This document is based on the assumption that libraries, archives and museums have shared research interests. We can identify several broad goals which underpin these, and which encourage collaborative activity between libraries, museums and archival institutions. These include:

- To release the value of Europe's scientific, industrial and cultural heritage in creative use by its citizens.

- To engage with the cultural identities and aspirations of Europe and its peoples.

- To develop practices appropriate to upholding the values and purposes of the library, archival and museum traditions in a digital environment.

- To explore what it means to develop virtual civic presence.

- To explore sustainable economic models which support both development and continued equitable access to the cultural heritage.

A feature of change is that we have no settled vocabulary. Some terms may have partial or sectoral associations, which are not commonly shared. This might be within particular curatorial traditions (library, museum or archival), particular disciplines, or particular national or language contexts. We adopt the following terms, and explain them here to ensure shared understanding while acknowledging their imprecision.

|

The Vision

Archives, libraries and museums are memory institutions: they organise the European cultural and intellectual record. Their collections contain the memory of peoples, communities, institutions and individuals, the scientific and cultural heritage, and the products throughout time of our imagination, craft and learning. They join us to our ancestors and are our legacy to future generations. They are used by the child, the scholar, and the citizen, by the business person, the tourist and the learner. These in turn are creating the heritage of the future. Memory institutions contribute directly and indirectly to prosperity through support for learning, commerce, tourism, and personal fulfilment.

They are an important part of the civic fabric, woven into people's working and imaginative lives and into the public identity of communities, cities and nations. They are social assembly places, physical knowledge exchanges, whose use and civic presence acknowledge their social significance, and the public value accorded to them. They form a widely dispersed physical network of hospitable places, open to all. They will continue to fulfil these roles, as people wish to enjoy the physical experiences they and the use of their collections offer.

However, we are now seeing the creation of new places which offer a new type of experience, a global digital space based on the Internet and other digital networks. Memory institutions are actively connecting their collections to these emerging knowledge networks. They are creating innovative network services based on digital surrogates of their current collections in rich interactive digital environments. They are focusing their traditional curatorial values on the challenges of the rapidly changing and growing digital resource, and developing relevant practices to support its use and management over time.

The archive, library and museum communities are addressing these issues within their own curatorial traditions and organisational contexts, and within specific national or other administrative frameworks. They are exploring how to provide learning, research and cultural opportunities, and how to identify and grow new communities of users. They are developing strategies to manage the physical, the digitised, and the born-digital as complementary parts of a unified resource. They are developing strategies for the initial investment and managed intervention that is required to preserve the value of digital resources. They are ensuring that 'born-digital' documents and artifacts become integrated into the cultural record, by being organised and documented so that they will be accessible, and become a part of the memory of future generations.

At the same time, they recognise their convergent interests in a shared network space. This convergence is driven by the desire to release the value of their collections into this space in ways that support creative use by as many users as possible. They recognise their users' desire to refer to intellectual and cultural materials flexibly and transparently, without concern for institutional or national boundaries. To support this, they recognise the need for services which provide unified routes into their deep collective resources, which protect the value of their resources in an environment of easy access and reuse, and which ensure the authenticity and integrity of resources. They wish to enhance and personalise their offerings through the collection of data about use and users, while preserving privacy. These aims pose shared technical challenges, but also highlight the benefits of concerted attention to business and policy issues. There is advantage in working together to develop business models which recognise the long-term ownership costs of digital media while preserving the public interest in equitable access; to establish and promote best practice for content creators and others which reduce the long-term costs of data ownership and enhance its use; and to explore what it means to develop cultural institutions in a digital environment.

Finally, they are unified in the belief that without the rich cultural resources memory institutions offer, emerging network places will be impoverished, as will the lives of the people who assemble there.

The Challenge

The digital medium is radically new. Although there is continuity of purpose and value within cultural institutions, these exist alongside a fundamental examination of roles and practices. The costs of developing necessary roles and sustainable practices will be high, as will the social and organisational costs of change and institution building. However the costs of not doing so will be higher, as the cultural and intellectual legacy to future generations is entrusted to a house of cards built on a million web sites.

The Challenge of Serving the Active User

The focus of service delivery is becoming the active user in a shared network space. The user wants resources bundled in terms of their own interests and needs, not determined by the constraints of media, the capabilities of the supplier, or by arbitrary historical practices. The growth in the variety, volume and volatility of digital resources means that effective use depends not merely on pointing people to resources, but on supporting selection, aggregation and use. It may mean providing interpretive environments in which resources are situated in relation to wider contexts. It may mean supporting reuse and repackaging of materials.

Human attention is more valuable than computing resource, and it should not be wasted in unnecessary tasks. Access and use may be situational: the 'information landscape' will be adapted to the needs of users or groups of users, rather than to the constraints of particular media or systems. These factors shift the emphasis of automation from inward-looking collection management to outward-looking services to the user.

The Challenge of Living with the Radically New

What is a 'document', or a 'publication', or an 'exhibition'? We often cannot 'see' a digital resource, we cannot sense its scale or scope, or its internal organisation. Nor can we always think in terms of traditional analogues: for example, we cannot simply 'print out' meteorological data, which may occupy gigabytes on disc. Data and programs may be integrated in complex applications, difficult to disentangle. Occupying a network space shifts the emphasis from standalone services constructed for human visitors alone, to services designed also to be visited by automated services which provide aggregation, filtering, selection or other services to human users. Users may interact with resources through digital library services, learning environments, games or exhibitions. The issues involved in providing services in such distributed, multi-layered environments are poorly understood. Everywhere we are living with new ways of doing things.

A major feature of the new is that fluidity replaces fixity as a dominant characteristic of resource creation and use. Fluid because data flows: it can be shared, reused, analysed; can be adapted, reconfigured, copied, and newly combined in ways which were not possible before. A resource dissolves into multiple individually addressable resources, or can be aggregated in multiple combinations. Resources can carry information about themselves, can communicate to automate processes or deliver new services, and can yield up use or status data which can drive decisions and inform behaviour. The creation and use of flows in a digital medium offer unprecedented flexibility, enhancing and augmenting services. However, with fluidity also comes the challenge of managing a fugitive and fragile resource:

- Fluidity foregrounds the need to support control and trust relationships. Just as the accessibility of resources is potentially enhanced in a digital environment, so is the ability to control that access in fine-grained and subtle ways. However, techniques for control lag behind techniques for access. The authenticity and identity of users, service providers and resources needs to be established. Where an increasing amount of cultural and commercial activity is based on the flow of signs and symbols, where our identities and services are increasingly mediated by digital environments, the nature of the rights associated with personal identities and intellectual products have profound implications for the management of the cultural heritage. The management of rights becomes critical as models based on the granting of rights to use data for particular purposes or durations become common. Technologies for control are the subject of significant attention and are essential for building institutions in a digital environment. As they become infrastructural we will see major further growth in commercial and other activity, as users and providers acquire confidence in the security of transactions, and the cost of doing business goes down.

- Data may be fugitive in several ways. Resources may be generated from some underlying resource, or dynamically created in response to a particular combination of circumstances. Data may not be recorded when created, they may disappear without trace if an appropriate business or policy framework is not in place, or they may not have documentation which provides the context, provenance or identity necessary for appropriate use. Data may only be available subject to particular agreements, and disappear when rights lapse.

- Data is fragile because 'content' depends on multiple structures and contexts which are vulnerable to change or obsolescence, whether these are physical media, encodings, logical structures, operating systems, interpretive and analytic tools, and so on. The long term costs of digital content ownership are only now being recognised and the need to manage preservation strategies to minimise those costs and secure the cultural record for the future is critical.

The Challenge of Planning for the Radically Unpredictable

Not only is change rapid, it is unpredictable. The transforming influence of the Web was not predicted several years ago, nor was the rapid takeup of e-mail. However, this is not a technological issue alone. As networking becomes pervasive of more parts of our lives, the complex interdependencies of technology development, service provision, business models, and user behaviour make innovation, reconfiguration and unpredictability integral to practice.

As service, technology and business opportunities co-evolve, new service provider configurations or divisions of responsibility will emerge. These may include third party resource discovery, authentication, or ratings services; long-term archiving facilities; or a new class of 'broker' or 'mediator' service which provides a single point of access across distributed collections. User behaviour will be shaped by and will shape opportunity and development.

This unpredictability emphasises the need for approaches which do not lock providers into inflexible or unresponsive offerings, and which support movement of data and services through changing environments. Without such approaches investment will be wasted and data will potentially be lost or difficult to use.

The Challenge of Institution Building

Over the last years, emphasis has shifted from technology development to serving users and managing content. However, procedures are still preliminary or provisional, awaiting agreements or technical developments which will provide routine and predictable services. They have often not become part of 'business as usual'.

This is part of a wider institutional flux. Institutions are relatively persistent embodiments of values and practices organised around particular goals, and we only beginning to sense how institutions will be built and modified in digital spaces. What is the institutional context of the library, of the museum, or of the archive, as they evolve and as the expectations and practices of their users evolve. And, importantly, as the institutions of learning and culture, of trade, of civic engagement, and of entertainment also evolve, altering patterns of relatedness and inclusion.

Development will depend on agreed business models, on an understanding of the role of public services in a digital environment, on emerging agreement about roles and responsibilities. These in turn will depend on more mature information infrastructure, including the ability to conduct commerce, to identify and authenticate users and content, to develop personalised services, to guarantee persistence and predictability. Institutions secure stable services.

The Way Forward

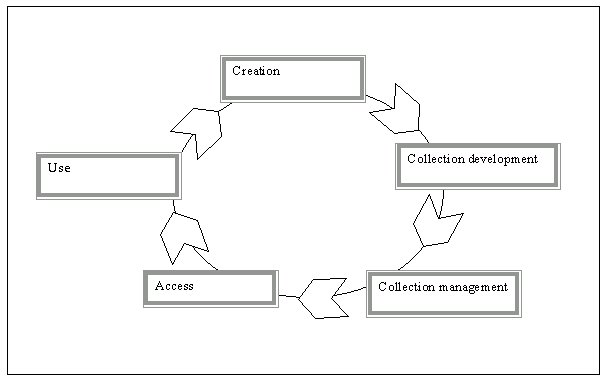

A life-cycle approach to the creation, management and use of resources emphasises the interdependence of choices in the life of cultural content. A choice made at any stage may ramify throughout the life of a resource, facilitating or impeding its appropriate flow through different custodial and use environments, and its ability to be an agile component of information and learning environments.

We discuss a research agenda based around the life-cycle presented in the accompanying figure. There has been a historical separation between the 'supply-side' interests of memory institutions, traditionally focused on the management of collections, and the interests of users and creators of cultural content. However, a significant feature of the digital environment is that memory institutions become centrally interested in supporting the creation and use of cultural content in more direct ways, as institutions and their users share the same digital space. For example, archival institutions wish to influence the format of the records transferred to them, so as to reduce the costs of management and ownership. Similarly, libraries, museums and archives are increasingly interested in serving up resources in such a way that their use is encouraged as active components of exhibitions, learning environments, and so on. Services which manipulate or analyse various types of data may be provided alongside the data itself. And of course, memory institutions are increasingly creating digital surrogates of items in their collections, or repackaging digital items in new offerings.

In what follows, different stages of the life-cycle are considered separately, with a concluding piece with gathers some organisational concerns. We consider the following life cycle stages, acknowledging that these are not definitive or exhaustive: collection development, collection management, access (including discovery and retrieval), use, and creation.

It is important to note that this document concerns itself with the life of cultural content in relation to the interests of memory institutions and their users, not in a wider context. A different perspective would yield different stages and emphases. Special attention is given to questions of access to cultural resources and network services, as increasingly, all operations will be carried out in the environment it describes where actors are supported by variously assembled network services to carry out their tasks.

Accessing Resources and Services

Memory institutions provide and use many network services to disclose and deliver their content. They are individually valuable, however they do not yet seamlessly work together or rely on each other for services. They do not communicate easily or share content. For example, it is not yet common to interact with more than one catalogue at a time. At the same time, as there is more development in a network environment additional network services are required, authentication for example.

This variety is potentially confusing and adds effort for the user or developer who has to discover what is available, cope with many different interfaces, negotiate different authentication systems, work out terms and conditions, manage different results, and move data between services. In the current environment, the collection of information about a particular topic - Darwin and finches, for example, as in the accompanying sidebar - is inhibitively labour-intensive. One has to know quite a bit, and do a lot of work, to get effective results. Some of this work is mechanical - it would benefit from being automated. The focus has been on the automation of individual tasks rather than on the automation of end-to-end processes, the sharing of content, or other examples of communication between tasks.

In a shared network space, a new way of working is required, one which recognises that network services do not stand alone as the sole focus of a user's attention but need to be part of a fabric of opportunity. Services need to be aggregated in support of business objectives and user needs. They need to be able to pass data between them - between a search service, a requesting service, and an accounting service, for example. This requirement is driving an interest in 'content infrastructure', which works towards 'plug and play' infrastructure for discovery, use and exploitation of content in managed environments. Monolithic applications are being broken down and reconfigured as systems of communicating services.

What services will be deployed by libraries, archives, and museums? Some they will provide themselves; some will be third-party services used by them to augment their own. They will also have to consider how these services are combined in helpful ways. We consider some network services here in very general terms in the next section, and issues arising from their combination in a following section.

Some Network Services

This is an indicative list, whose purpose is to illustrate the variety of activity; it is not exhaustive and adopts an inclusive view of 'service'. The services discussed are provided in various ways and are at different levels of granularity.

First and foremost, libraries, archives and museums disclose and deliver cultural content.

- Disclosure services. Memory organisations disclose their resources through catalogues, finding aids, and related tools. Effective disclosure is critical to discovery and effective use. The characteristics of digital information above introduce additional descriptive requirements. Resources, collections and services need to be characterised so that human and machine users can discover and make effective use of them.

- Content delivery services. They make cultural content available in different ways, as flat files, as databases of images or documents, and so on. As we have discussed elsewhere, content is increasingly presented within interpretive environments.

- Rights management services. The automated management of rights will be a critical service as organisations wish to protect the value of their resources and describe appropriate use.

Some areas of development are especially important as they can lever significant expertise and knowledge within the library, museum and archival traditions to provide new types of service:

- Resource discovery services. These support the discovery and selection of services and resources. Typically they might provide data about the content and context of collections, service profiles required to make use of them, and terms and conditions under which they are available. An example of a resource discovery service is the so called 'subject gateway'.

- Terminology and knowledge representation services. These may provide vocabulary support for query expansion or indexing. Translation and dictionary services are also appearing. Memory institutions have invested significantly in knowledge representation activities, which may increasingly appear as accessible resources in their own right, to support discovery or metadata creation.

- Ratings services. These may be used to associate values from some scheme with resources. For example, they might be used to indicate relevance to a course of study, or collection strength in a particular thematic area. Ratings data may be used to delimit or rank results in particular ways.

Some services will become 'infrastructural' in the sense that they become services which are predictably and consistently available in a shared way across providers, rather than being developed on a per-provider basis. General third party services might include:

- Authentication services. In the new shared space of the Internet, users and services may have no prior knowledge of each other. Users, services and resources may need to be authenticated to provide assurance that they are what they purport to be. Currently authentication tends to be service specific, and hence fragmented. Multiple challenges are one of the main inhibitors to current network use, while the absence of a common approach inhibits suppliers. A robust approach to distributed authentication is a major requirement for future services.

- E-commerce services. Memory institutions will increasingly provide charged for services, and common approaches will be needed.

- Caching and mirroring services. These services will become more common within particular communities of use to assist economic use of network resources.

Some services might begin to be shared within the memory domain, perhaps using generally available infrastructural services (such as directory services for example). Examples might include:

- Schema registry services. A schema describes the structure (attributes and relationships) of a data item such as a resource description. Schema registries are central repositories which can provide human- or machine-readable schema descriptions, and will provide infrastructure for support of distributed access, use and preservation of resources.

- Location services. We use this phrase for the resolution of identifiers into locations. These may be concise identifiers, where there is ongoing research into the design and deployment of persistent identifiers. Such deployment will depend on technical and business solutions, which are still being investigated. Persistent identifiers will be valuable in a range of application contexts. Or they may be less concise, in the form of a citation which requires matching against holdings data to determine location. This scenario is one which is being explored in a library context where multiple copies of items may exist. The development and deployment of identifiers, and their interworking, present significant R&D challenges.

Memory institutions will develop particular services to enhance access to their resources, individually or collectively:

- User profile services. These may be necessary for personalisation services, and store data about user permissions, profiles, and behaviour. Currently they tend to be service specific and redundant. Third party services may emerge, and there are clear links to authentication and other services. How to characterise user preferences, behaviour and privileges in acceptable and useful ways is an open question.

Some basic services may be used to support other activities, for example:

- Search services. These may have to iron out differences in underlying metadata or indexing schemes. Searching across domains presents particular challenges given their different underlying content models and descriptive standards. Search services may provide support for query routing, to avoid unnecessary use of resources. Different search services may be provided: for textual material, for image content, and so on.

- Request/order services. These manage the request transaction from placing a request to its successful completion. They need to interwork at technical and business levels, and communicate with accounting, billing, authentication and other services. There is some standardisation in the libraries area, but approaches tend to be fragmented by service.

- User interface services. Services may be presented in different environments: web-based, immersive, or through some form of visualisation.

Combining Network Services

Increasingly, such services will be built from other communicating services. Services may share some basic services and infrastructure within agreed frameworks for communication.

For example, resource discovery services may report on the availability of services, may use location services to identify instances of resources (mirror sites for example), may be combined with user profile or ratings services to refine selections, and so on. A service which mediates access to the holdings of several memory organisations might provide support for discovery and selection of services, manage service requests, translate formats, aggregate services, consolidate results, manage authentication and financial transactions, and so on.

Such 'mediator' or 'broker' services, which provide consistent access over other services and which allow them to communicate, will become more important. These may be implemented in various ways, for example as bespoke applications or as networks of reusable components (e.g. software agents). Communication will benefit from agreed APIs (application programming interfaces) and data exchange formats. Increasingly, applications will be built within a distributed object framework.

In order for a client or broker service to access a network service it must know: the location of that service and details of how to communicate with it. We call such details a 'service profile'. For example, in a particular case, such a profile might include the access protocol (which may be the simple web protocol HTTP, a search and retrieve protocol, a directory protocol or other form of protocol depending on the service being accessed); the request format (which may be defined by a query language); and the schema(s) relevant to the service (for example the metadata format in use).

Interworking across services will not be achieved by enforcing uniformity. It is not desirable, nor would it be possible, to suggest that network services converge on a single service profile, although agreement over profiles for classes of service would facilitate interworking, as would a mechanism for sharing service profile descriptions. A variety of service profiles will be in use across cultural domains, reflecting the variety of services they make available and the different curatorial traditions and professional practices in operation.

There are significant research and development challenges in the development of distributed content infrastructure. Some areas which require attentions are:

- Architectures and models. Work on how component services might be assembled to support particular business needs, and on interworking requirements will be necessary. An architectural approach helps identify interoperability points and provides a shared framework for development.

- APIs (Application programming interfaces) and exchange formats. Agreed interfaces and exchange formats support communication between services. For some services, such agreements do not yet exist.

A project team wants to find out more about Darwin's finches: they want some information about how they contributed to his theory of evolution. They are doing a part-time course, and are exploring the leads provided in the course pack.

|

- Metadata. Metadata is increasingly pervasive of network environments. It is data which characterises objects and their relationships in order to support effective use and behaviours. The design and deployment of metadata is now central to much network activity, both within particular domains and to support working across them.

- Demonstrators and services. Examples of broker services exist within the libraries, archives and museums area, some funded by previous European programmes. There are few examples of cross domain brokers, and we have limited experience of technical and organisational issues of assembling them. It is clear that services increasingly rely on each other and brokers will support relevant communication between them to create higher level services which meet particular business needs or quality of service objectives in distributed object environments. We need experience of developing such services.

Use

Memory institutions will support use in ways which reflect new opportunity, and the changing behaviour and needs of active users. There is clearly a close relationship between resource use and adjoining operations in the chain: resource access and resource creation. Areas for investigation include:

- User behaviour. Our understanding of user behaviour and requirements is often limited by expectations based on current services or soon-to-be-superseded practices. Service development needs to engage with the aspirations of users over time as possibilities change. We know very little, for example, about what users might expect from cross-domain services. How ought library, archive and museum resources sit together? How do we support services through monitoring of user behaviour, with consequent privacy issues?

- Service contexts. As services and resources appear as components in different contexts, issues of presentation and interaction occur.

- Cultural institutions increasingly embed resources in wider interpretive contexts, whether these are exhibitions, curricular materials, or other guiding material. These might be realised through structured, searchable, sharable documents which provide instructional, learning, navigational or other interpretive narratives for services. Some standardisation would support the sharing of such narratives, the use of common contextual knowledge (personal and institutional histories for example), and the structured collection of audience evaluation.

- Interfacing to other environments. Many users will interact with cultural services through some other mediating or broker service. Learning environments, digital library services and games are important examples, which will become increasingly important. It is important that cultural network services can be made available through these environments, and that appropriate interfaces exist which allow the effective sharing and communication of content.

- User input. Increasingly service providers are interested in receiving user input, commentary, or contributions which may be incorporated alongside other materials. Are there shared issues surrounding such interaction? In some cases there is value in collecting user analyses or interpretations of data for wider sharing. A data archive may have an interest in providing access to analyses of data alongside the data itself, for example.

- Information and cultural landscapes. We have little experience of the distributed service scenarios which are emerging. Interactions may be based on multiple communicating services, in ways which are opaque to users, or in which sets of layered services have to be presented meaningfully to users, and in environments which are increasingly personalised or adaptive. For service providers they may have to consider issues of how their data might be presented in environments over which they have no control.

- The user interface. Services, or such 'landscapes', will be presented at different user interfaces. Immersive environments, visualisation, and other approaches will benefit from structured approaches at relevant levels, which allow such different user interfaces to be written to the same underlying services.

- Adaptive services based on knowledge of use and users.

- Promotion and marketing. It is usual to modify services based on data derived from use and users. The techniques for gathering such data, and the type of data which can be collected, are changing. As are the techniques for immediately modifying service based on such feedback.

- Personalisation. The use of personal profiles (which record such data as privileges, preferences, and past behaviour), and other techniques are increasingly used to personalise services.

- Reuse and exploitation.

Creation

Memory organisations create digital cultural content themselves. They can influence the creation activity of others, whose outputs they collect or are transferred into their holding. They can provide resource creation services to their users. In each case, they have a shared interest in promoting future use and in minimising the costs of accessioning and management, by working to develop good practice and the tools to support it.

- Best practice guidelines. Authoritative guidelines based on emerging best practice will achieve scale economies by accelerating the learning curve for resource creators, and support effective use and reuse. They will also assist more effective use of funding, reducing redundancy of local investigation. An indicative list of what such guidelines might cover include: digitisation of existing resources (e.g. selection criteria, applicability of particular techniques against resource type and anticipated use, advice in relation to particular resource types); documentation and metadata (e.g. use of particular schema, vocabulary and authorities guidance); processing (scanning, etc); control (e.g. techniques for ensuring authenticity and integrity); preservation issues; presentation (e.g. image formats and resolutions); conventions for recording (volume ranges). Many guidelines currently exist, and there is no shared understanding of the issues to be addressed. An overall life-cycle model is a heuristic tool in establishing needs. Such guidelines will be useful in supporting the development of shared approaches to the creation of the intellectual and cultural record.

- Access to techniques, tools and services. Users will occupy different environments. In some cases, memory institutions may provide them with creation, editing and other tools.

Developing Collections

Libraries, archival institutions and museums have developed their collections in line with specific missions and according to different curatorial traditions. A national library may benefit from legal deposit arrangements, for example. Component collections may be built up to meet some particular interests, or may be transferred into memory institutions as complete entities. Collections may be unified by theme, by medium, by ownership, by provenance, by administration. Some large cultural organisations may have contained a combination of library, archival and museum collections, managed by staff from appropriate professional domains. Memory institutions exert different levels of control over the materials they accession. How can we expect the nature and composition of collections to change in the digital environment?

- What is a collection?

- Collections have been unified by collocation. What does it mean to develop a collection in an environment where collocation is not a requirement? What criteria govern its assembly? How is it managed? Where resources are brought together from different locations to create a collection, what framework needs to be put in place to ensure its continuity?

| The Science Museum is in the process of creating a series of narrative-based digital documents, 'Exhiblets'. These are intended to perform a number of functions, including acting as online resources for some of the thousands of collections-related enquiries the Museum receives each year. They are valuable learning resources and provide audience-friendly access to the vast range of collections held by the Museum. Exhiblets draw on information held in various forms, managed by a number of domains across the Museum and beyond. Comprising information drawn from the Museum collections, the Museum's Library, its Archive and existing publications, Exhiblets depend on information being made accessible from these domains at item and collection level, and place this content in a narrative context. The narrative provides a means of leading the user into the subject area and adds meaning to the structured information, making links between resources from the three domains, and building a story around the associations which can be made. For example, an Exhiblet on the Portsmouth Blockmaking Machinery tells the story of the evolution of the first ever suite of machinery used for mass production. Descriptions and images of the objects themselves, held at the Science Museum and also at other museums across the country, are placed in the context of the early stages of the industrial revolution. Reference is made to the holdings of the Science Museum Library, providing a technological and historical background. Letters between the inventors and manufacturers are drawn from archival sources and biographical information tells the story of how designers and manufacturers worked together to produce the machinery. The potential for this type of format is great, providing as it does a jumping-off point for a user to follow the trails which lead off from this narrative. Implementations of these Exhiblets will also provide users with the opportunity to provide their own knowledge which the Museum may be able to incorporate into the resource store for use in developing other resources. Curators as 'knowledge providers' work with researcher-editors to make the production process as simple as possible. However there are a number of issues which have yet to be resolved if this type of resource is to fulfill its potential. |

- How do we begin to build cross-domain collections, which assemble resources historically curated within different traditions? What are the benefits to users of such collections?

- Mapping collections.

- The different curatorial traditions have different content models which direct documentation practices. Libraries have tended to describe individual items - journals or books - but not the collections which contain them. Archives and museums have developed multi-level approaches to description of collections and their parts. Emerging distributed approaches have highlighted the importance of high level collection description to assist in navigation, discovery and selection of cultural content. Agreed metadata and other approaches need to be developed, which work across the domains.

- Managing collection development.

- Digital collections depend for their usefulness on critical mass. This in turn depends on a strategic approach to collection development, which encompasses a view of user needs and the wider availability of resources.

Management

Libraries, archival institutions and museums deploy long-standing procedures and professional practices in the management of their collections. These have been adapted as they move to 'hybrid' collections, collections which contain physical materials and newer digital material. New procedures and professional practice are preliminary, are often exploratory or experimental, and may be confined to limited, highly labour-intensive operations. Routine approaches will benefit from down-cycle technical and business agreement, but practice is still ahead of standards. This will be increasingly unsustainable as memory institutions have to manage large-scale digital repositories, accession large volumes of heterogeneous digital materials, and organise them for immediate use and long-term access. Such digital materials may be internally complex, multiply linked, and created in different computing environments. Fine-grained rights management frameworks will need to be deployed. Effective management of the radically new, and the radically unpredictable, poses many challenges.

- Protocol support. Protocol support for sharing and managing content is very limited. Resource management depends on bespoke development, which is expensive. Similarly, customised approaches have to be developed to track the life events of a resource.

- Rights management. In a network environment the assignment and assertion of rights becomes central. Memory organisations will wish to assert the conditions under which users of different sorts can access or exploit their collections and parts of their collections. Fine-grained control will be required to cover the ways in which resources will be used.

- Developing new practices to manage large digital repositories. Systems support for routine practices which can be automated will be essential. For example, procedures for accessioning material which involve establishing the authenticity and integrity of a resource, determining its format, validating and managing associated metadata and control data, assigning identifiers if necessary, and so on, are needed. Addition to a collection may involve many operations, across different data stores, with many associated checks and changes. We have little experience of managing large digital repositories of complex objects. There are points of contact and comparison here with general knowledge and document management approaches.

- Serving current users. Resources need to be made available through network services. Current network services are often limited when compared to local services. There is limited externalisation of structure or content, it is hidden behind web gateways, and not accessible to users or clients. Network services are preliminary and partial; fuller services need investigation.

- Serving future users. The viability of digital information over the long-term needs to be secured. Strategies for migration, emulation and technology upkeep are all being explored within experimental contexts. Many issues are outstanding: preserving content, context and structure; keeping metadata and control data valid and in appropriate relation with content; dealing with encrypted data; IPR issues; approaches to dynamic or externally linked materials; event histories; and so on. Early experience points to the lack of consensus as to best approaches; the significant ownership costs over time of digital materials and the need to reduce them through routine, automated practice; the technical complexity of some proposed approaches; the continuing development of formats and resource types.

- Monitoring use. As resources and users live in a digital space, the opportunities for capturing data increase. Common frameworks for management information systems and decision support systems have been developed; these need to be extended across domains.

- Managing hybrid collections. Memory institutions are interested in the cultural record in its historical continuity and full current breadth. They are concerned to manage the physical, the digitised, and the born digital as complementary parts of the fabric of knowledge. To achieve this they will have to manage hybrid physical and digital environments, ensuring seamless transition between them.

Organisational Frameworks

We have suggested that technology, service and business contexts are coevolving to shape opportunities and obligations in a new, shared network space. This has some implications. There are greater opportunities for scale economies as the level of infrastructure rises, in the form of technology or utility services. A distributed service environment requires levels of agreement about how services and organisations relate to each other, as services are recognised as part of a fabric of provision rather than as standalone offerings. New roles and divisions of responsibilities are emerging. And finally, new practices must be institutionalised to secure their stability.

- Rising level of infrastructure.

- We are moving from a phase of monolithic applications, where services were provided on an application by application basis, to one where common services are increasingly split out into infrastructure. It is the scale economies and interoperability which this delivers which is driving much current web development, as greater support for structured documents, for security and encryption, and for other common services is being worked on. We are likely to see infrastructural support for distributed authentication, for e-commerce, for distributed authoring, for ratings, and for metadata management, which will all impact on how cultural content is served up.

- In a related trend, third party suppliers are emerging to supply these and other services as utilities. Business models for such services are immature.

- A fabric of provision.

- It is important that services interwork. This will not happen without agreement. Such agreement requires management, and a range of consensus making bodies exist. These need to be reviewed in the light of emerging cross-domain agendas and new distributed environments. Agreements will increasingly depend on infrastructural services which support communication as and when required without the need for prior knowledge. Such services include registry and directory services, which may disclose information about the technical characteristics or content of resources. Particular areas where agreement would support the emergence of services which address the full range of cultural heritage include user profiles, collection description, document type definitions, and search and retrieve protocols. We are seeing a convergence of interests emerging through practice as new services develop; this needs to be supported through top down activity also.

- Efficient use of network information will increasingly depend on effective use of mirroring, caching, query routing and other techniques, and their interaction with discovery and other services. Such activity would benefit from attention. We still have much to learn about sensible distribution of storage and processing. For example, the library community is assessing the benefits of distribution of access in comparison to the distribution of collections (e.g. use of distributed techniques to keep union catalogue up to date compared to use of distributed techniques to search across individual catalogues).

- Roles and responsibilities.

- Memory institutions are exploring new roles. New organisations are emerging to fill new niches in the developing service environment. Who will be responsible for long-term archiving of commercial publications? Who will administer identifier schemes? Who will provide cross domain resource discovery or rating services? Explorations are taking place against uncertain business models, and a shifting environment. Memory institutions will have to consider these issues and migrate project or exploratory activity to sustainable services based on developing experience.

- Such change creates special challenges for professional and organisational development. Staff may develop new roles (editors, producers), may have to deal with new business challenges, and may have to acquire new skills. Organisations have to decide what their business is, may have to reprioritise or refocus, may have to enter into new collaborative or business liaisons. The requirements for development and training need to be established.

- User involvement. Memory institutions are developing interactive services, are inviting contribution and selection, are entering into collaboration with their users. In what way should these activities develop? How will they be managed?

- Institution building

- Economic and business models. Digital provision is changing the cost structure of creation, supply and use. The nature of value added in new creation and demand chains is still being assessed. Service may be experimental or supported by development funding. Market making mechanisms - billing and charging, trust mechanisms - are still immature, which inhibits some types of activity. These and other factors make the development of valid economic models difficult. There are important issues to be addressed where concerted action is important. These include the development of common positions on the reuse of cultural content, on what it means to provide equitable access, on commercial partnership. Many of these will need to be developed on a per case basis, but there is also merit in developing shared public sector views which establish guiding patterns of expectation in future provision. Memory institutions may have different responses, and there are important domain differences arising from the nature of the collections involved and the historical roles of organisations.

- Services and practices need to become institutionalised. Institutions secure stable services, but take time and experience to establish. They need to reflect need and support emerging practice. It is important that effective international, cross-domain fora emerge in which consensus can be reached about preferred future directions, and in which memory organisations can reduce the uncertainty of change, and any potential perceived threats to the status quo.

- Institutions will increasingly depend on technical infrastructure which support the development of predictable, trust relationships. The authenticity of providers, resources and users needs to be established. A framework for rights management and commerce needs to be in place. Much of this activity will be outside the specific responsibility of memory institutions: it will be a part of wider provision. However, memory organisations need to be alert to the ramifications of wider development for the construction of their own services, and work together to pursue shared interests.

- A developing lexicon. Individual curatorial traditions have developed their own ways of talking about concepts and objects. In several cases, words may be used across traditions with difference emphasis or sense. A shared glossary would usefully support the development of shared interests.

- Interaction with other institutional contexts. The institutions which support learning and research, commerce, entertainment, and government are changing, which will in turn impact on how memory institutions develop. These changes need to be understood, if memory institutions are to develop in ways which ensure their contrinued relevance.

- Civic presence. The digital information environment is still 'under construction'. Memory institutions have been instruments of civilisation, of engagement, of communication and community building. They are a part of the civic fabric of our lives. How will such presence be achieved in digital information spaces? Do we even yet know what questions to ask?

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Pat Manson, DGXIII, for her support during the preparation of this document. We are also grateful to the several people who have commented on the document in draft. Prepared for DGXIII in the programme area: COLLABORATION BETWEEN ARCHIVES, LIBRARIES AND MUSEUMS UNDER KEY ACTION 3 (MULTIMEDIA CONTENT AND TOOLS) OF THE INFORMATION SOCIETY TECHNOLOGIES PROGRAMME UNDER FP5 (November 1999)

Author Details

Lorcan Dempsey |