Convergence of Electronic Entertainment and Information Systems

The past

Video games have been around for a lot longer than most people realise. Many people can remember playing games on their ZX Spectrum (1982), or even their cartridge-based Atari VCS (1978). However, before these systems came into being there had already been a decade of video game development, mostly based in the US and Japan.

The first recognised games console was the Magnavox Odyssey [1] in 1972. This US-produced machine sold around 100,000 units in three years, and at the time was considered to be revolutionary. Despite the lack of colour and sound, and the limitations of the system resulting in a maximum of three basic graphics on the screen at any one time, imaginative software led to the Magnavox being widely acknowledged as the first true games console.

As the seventies progressed, several games consoles were launched with varying degrees of success. A recurring factor in the success (or otherwise) of many of these consoles was the actual software support that they received. Many consoles, despite being superior in power and capability to others on the market at the same time, generated disappointing sales due to the lack of games. Surprisingly (or depressingly), this situation still occurs today, and has indirectly led to the Playstation becoming the clear market leader over the last two years.

In the late seventies, Atari launched the VCS system, which can be considered to be the first mass-market dedicated games console. As well as bringing in-home gaming to the masses, the console also caused the emergence of several games-related companies and enterprises that are still going strong today, most notably Namco.

Also in the late 70’s, (Sir) Clive Sinclair appeared on the scene. Fresh from producing some of the first digital watches and calculators, Sinclair moved into the small home computer market. The first mass-market Sinclair computer was the ZX80 (based around the ZX chip, which was named after…well, look at the two letters in the bottom left corner of your keyboard). The ZX80 possessed less than 1K of memory and extremely limited visuals, but still proved popular. Surprisingly, a close version of the same 8-bit chip was used inside the Nintendo Gameboy, the world’s most successful handheld games console, which still sells strongly today.

In 1981, the predictably named ZX81 was launched, to adverts claiming that the computer could run a nuclear power station. The machine, which resembled a rather fat door wedge, possessed 1K of memory, a membrane-based keyboard, and visuals that were still limited but could be manipulated into surprisingly good (black and white) graphics. Several companies produced software and hardware, thus enabling people to attach a keyboard and a memory expansion pack offering a “massive” 16K of memory. Consensus at the time in our school playground was that no-one was ever going to write something that would fill 16K of memory and thus the add-on was a waste of money.

In 1982 Sinclair launched the Spectrum [2], and home-based gaming was changed forever.

The machine came in two flavours, 16K and a “massive” 48K. The machine was a huge success, and is still many people’s first clear memory of video gaming at home. Despite the rubber keyboard, the basic “variations on a bee trapped in a jar” sounds available, the official printer consisting of a device which “burned” text onto a silver-coated paper, and the fact that games took up to five minutes to load from a tape recorder, the Spectrum was a runaway success.

It is notable that many of the top games designers and developers of the last half a decade from the UK and Europe first cut their teeth on a Spectrum. The format was supported by a wide range of established and new games producing companies. Perhaps the most celebrated of these was “Ultimate (Play the Game)” [3], who produced a string of hugely popular titles, including Jetpac, Manic Miner, Atic Atac [4], Lunar Jetman and UnderWurlde. Many thousands of children managed to persuade their parents that the Spectrum could help them with their schoolwork, whereas on purchase it was used almost exclusively as a games machine (this trend probably continues today). It is notable, in these days of games costing between 30 and 60 pounds, to remember the outrage when the price of games for the Spectrum “broke through” the 5 pound barrier.

There are many fan sites dedicated to the Spectrum out there on the Internet. One of the best is the Jasper ZX Spectrum Emulator site [5], which allows you easily to play faithful conversions of Spectrum games through your Web browser on your PC.

However, the Spectrum did not have it all its own way. The US company Commodore launched the VIC-20, followed by the C64. This had a “ridiculously excessive” 64K of memory and better, though far fewer, games than the Spectrum. However, with purists, some games developers, and people who wanted to use a proper keyboard, the C64 was the preferred option in the early eighties.

By this time, a large number of games companies were thriving in the UK, Japan, the US and to a lesser extent mainland Europe. Many of these companies would last less than two years, due to the constant need to produce and market large quantities of titles. Even with the limited capabilities of the machines of the day, games were taking an increasingly large amount of time to develop.

Throughout the first half of the eighties, games-based machines from a range of companies were launched to varying degrees of success. Some proved popular due to the quality of their graphics and key titles being emerged for them; others, most notably the Acorn BBC micro [6], proved popular due to their perceived educational capabilities. The BBC micro, despite being nearly 400 pounds, was extremely popular, largely as it was used widely in schools and actively supported by the BBC.

The BBC micro also spawned several well-known software titles, including possibly the first UK game that truly became part of a mass publicly-aware culture: Elite [7]. This was a fusion of outer space trading, “shoot ‘em up” and wandering, in an extremely non-linear fashion, through a beautifully rendered and vast 3D universe.

However, around 1984, the video games console market took a dramatic downturn, as machines more oriented to “practical work” became much more popular, especially in the US. Large numbers of people moved away from purchasing straight games-only consoles to machines on which they could use simple word processing, spreadsheet and other applications.

In the UK, Amstrad in particular started to produce machines that genuinely combined games playing with work and business applications. These machines possessed full and proper keyboards, and tape recorders or disc drives that were integrated into the machine to form a single piece of hardware. In addition, the early to mid eighties saw the marketing of machines by two Japanese companies in particular which were emerging in this field, namely Nintendo and Sega.

Throughout the latter half of the eighties, established console and computer manufacturers such as Atari, Sinclair and Amstrad launched new machines in order to try and gain a decisive market edge. Hardly any of these machines are in widespread use today, though some are still fondly remembered by many people; these include the Amiga, which is ferociously defended and supported by a small but passionate number of users and developers to this day, the Sega Mega Drive and the Nintendo SNES. In addition, by this time certain characters and brands were starting to become established and used across an “ancestry” of consoles; these included Sonic the Hedgehog, and Mario (as in Donkey Kong).

Into the nineties, still more consoles appeared. By this time, consoles were becoming increasingly complex, but most still achieved only limited success due to the lack of supporting software. Handheld machines also became widespread, most notably the Nintendo Gameboy which was sold with Tetris (to many games experts, arguably the most addictive game invented to date).

Around the mid-nineties, Sony released the Playstation [8], the machine that was to become the closest yet to an “industry standard games console” in the world. Nintendo followed towards the end of the nineties with a 64-bit machine, the unimaginatively named Nintendo 64, while the end of the decade saw the launch of Sega’s Dreamcast. Which brings us to the present…

The present

The computer and video games industry can be considered to be relatively mature, and comparable, in terms of trends, growth and turnover, to the music industry. In the UK, over 2 million games for consoles and the PC were sold in the week before Christmas last, generating some 50 million pounds in turnover. Console sales continue to rise, and characters from the gaming world, such as Lara Croft, have entered popular culture alongside pop and sports stars.

Games of today

People who have not played or seen computer and video games in the last few years are in for quite a surprise when they see the standard of graphics, detail, playability and speed in some of the leading games of last year and this. Each console has at least a handful of games that could be considered classic, or defining. These include a trio of shooting / stealth games, namely GoldenEye (Nintendo 64), Half Life (PC) and Metal Gear Solid (Playstation); and role playing games and fantasy adventures, most notably the Zelda series and Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time on the Nintendo, and the Final Fantasy series on the Playstation.

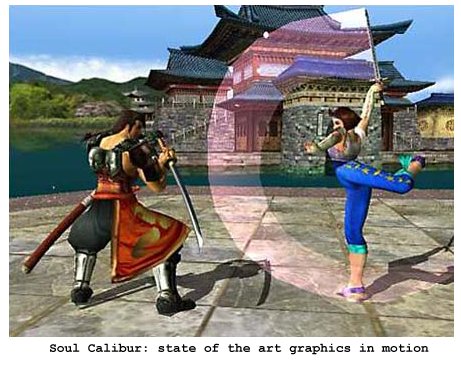

In addition there are fighting games, most notably the breathtakingly beautiful Soul Calibur [9], on the Dreamcast, and racing car games and simulators, of which Gran Turismo and Gran Turismo II on the Playstation are streets ahead of the rest (excusing the pun).

Multiplayer games continue to be popular. Clones of games such as Doom proliferate on both PCs and games consoles, though only on PCs can such games be played either remotely, or (as is more often the case) across a university or business network. There is a school of thought that argues that remote playing of such games is a purer experience, as you cannot see what the other players can see, as you would if you were huddled around the same console and television. However, an opposing point of view argues for the increased enjoyment that can be derived from beating someone who is in the same room, or sitting next to you.

Games consoles of today

There are currently three main games consoles that dominate the market: in ascending order of processer power, these are the Sony Playstation, the Nintendo 64 and the Sega Dreamcast.

The Sony Playstation

The Sony Playstation has been in existence for roughly half a decade and is by far the most popular games console in the world. Sales of the Playstation have passed 6 million in the UK alone, which equates to roughly one in every four households. Despite lacking the power of the other two contemporary rivals, the Playstation still outsells them both. In 1999, it sold over half a million units in the UK, compared with just over 50,000 Nintendo 64 consoles and nearly 90,000 Dreamcast consoles (though the latter was not launched until October).

The Playstation is a CD-based machine, complete with a library of games numbering some several thousand. However, of these games, the vast majority are of a poor quality, or are sequels or clones of particular genres. Football manager simulations in particular are frequently launched on this platform.

The Nintendo 64

The Nintendo 64 [10], has been in existence for roughly three years. Sales of the console have paled in comparison to those of the Playstation, despite the 64 being a superior machine. This is mainly due to the lack of games produced by Nintendo and third party developers. Frequently during its lifespan, several months have elapsed between the release of software titles which could be considered to be “classic” or “very good”. Despite this lack of key titles, those that were released are often considered to be amongst some of the best games ever released. It is especially notable that Edge magazine (considered to be the UK gaming magazine of distinction), in its “Top 100 games of all time” listing in the January 2000 issue, selected Nintendo 64 games for all top three places. These were, in ascending order, GoldenEye, Mario 64 and Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time.

Despite a relatively poor uptake in the UK (the US being the only country with respectable N64 sales), the console has many fans, and classic titles are still being produced on an occasional basis. The “sequel” to GoldenEye, Perfect Dark, is especially awaited. The console itself is cartridge based, as opposed to CD based. This has several advantages, namely the elimination of game loading times and the need for memory cards to save game positions. However, it has several disadvantages, the most notable being the higher cost of development and the higher cost of the overall game to manufacture and purchase, as opposed to games for the Playstation and the Dreamcast.

The Sega Dreamcast

The Dreamcast [11] is the newest console, launched worldwide last year, with a UK launch taking place in the autumn of 1999. Many people, including the author of this article, saw Soul Calibur in action on the Dreamcast and immediately handed over 200 pounds. This bought a standard CD based console with one controller. The console generated wide excitement at the time of its launch, due to its capabilities and the visual splendour of some of the games being developed for it; however, an infrequent release of quality games for this console has resulted in a loss of some momentum in the last few months.

The Dreamcast comes complete with a built-in modem, though this offers a relatively slow rate of online access equivalent to two-thirds the speed of contemporary PC modems. Despite the launch of the Dreamcast being delayed in the UK for three weeks while the online service was optimised, users have still to see any games which can fully exploit the online capabilities by allowing people to play against someone else in the same country (or even abroad).

The Dreamcast has several interesting add-ons, including a keyboard (which is not essential, but makes using the in-house developed and supplied web browser much easier to use!) and VMUs. The VMU (visual memory unit) allows game positions to be saved, and also allows mini-games to be uploaded and downloaded from the console, or even from a select few arcade machines.

The Dreamcast is similar to the Nintendo 64 in that despite the lack of games releases, it boasts several titles that can be considered to be leading edge or classic. These include the previously mentioned Soul Calibur, Shenmue, and Crazy Taxi.

Handhelds

The handheld game console market is still dominated by the Nintendo Game Boy, which has been gradually upgraded over time. The newest incarnation is a version with a colour display [12]. The Gameboy has been recently joined in the marketplace by the Neo-Geo, a handheld console with more detailed and faster graphics. However, the large library of games already available for the Gameboy ensures that it remains the market leader in this particular sub-division.

In addition, Nintendo hold the rights to Pokemon [13], a game that combines the fun of collecting football cards (except that you collect pocket monsters) with the combat scenario of games such as Top Trumps (in that your monster has to beat your opponent’s monster for you to capture it). The Gameboy hosts two Pokemon games, Blue and Red; to complete the game, users need either to buy both versions, or compete with someone holding a different version through a connector cable that attaches Gameboy units for multiuser playing.

Not surprisingly, Pokemon is, to the average six to twelve year old, an incredibly addictive game, and with marketing tie-ins such as clothing, songs, movies, collector cards and other ephemera, the income generated from Pokemon and Gameboy alone should ensure that Nintendo is active in the games console and software market for several years to come, irrelevant of other circumstances.

The PC

Conspicuous by its absence from this article so far has been the PC. This is not to say that the PC has not been used for gaming purposes: indeed, it has been a major games machine for the past decade and more.

However, the PC has one extremely major flaw which has meant that many of the top games software houses in the world have shied away from it as the platform of choice: instability. The PC can come in many flavours, with many different levels of graphics capability, memory capability, hard drive capacity, and other variables. Producing games for the PC requires a difficult balance between producing a game that will work on as wide a variety of machine permutations (and therefore a wide target market) as possible, while still being “cutting edge” enough to look impressive against other contemporary releases.

Therefore, the PC loses out to games consoles with regard to stability and the homogenous nature of said console for developing software. For example, with the Nintendo 64, there is one console with two options for the memory; either normal, or with an expansion pack. The games developer knows that developing a game that will work on one Nintendo 64 will work on any other.

In addition, a games console is ridiculously easy to use, compared to a PC:

- Put game into console

- Turn console on

- Play game

Compare this to a PC, where there is often an installation procedure, as well as patches to cover bugs and to ensure that the game operates on a wider permutation of machines. For ease of use, the console wins hands down.

But…

The PC has several advantages over the games console. These include:

- a hard drive, on which large amounts of information can be exchanged. Compare to a games console, which usually has no hard drive, and memory cards are bought and used to hold “saved positions” (apart from the Nintendo 64, which stores saved positions within the games cartridge).

- non-games software, which can exploit the hard drive and enable people to carry out tasks in addition to playing games, such as word processing, spreadsheet work, and programming.

- a keyboard! Simple, but very relevant. As the PC has a keyboard, large numbers of strategy games which require text or other complex commands have been produced for it. These include flight simulators (the Microsoft series in particular being well known), battle simulators, business and political simulators (most notably Sim City) and similar games.

- nowadays, PCs are usually either attached to a network or to the Internet via a modem. Within Higher Education, this has been the case for several decades, hence the use of PCs for online gaming of varying complexity and popularity, from within Higher Education institutions, for several years. Until the Dreamcast was launched, games consoles were usually “stand alone” devices, being unable to connect to each other or the Internet.

The future

In this final section, we examine some of the hardware that will be available in the next year or two, and identify a few topics of relevance to UK Higher Education.

Playstation II

The Playstation II was recently launched in Japan to a fanatical reception [14]. Despite heavy production of the console in preceeding months, many shops and stores received insufficient supply. The number of units sold is still unknown, though Sony were hoping to sell over a million in the first weekend of launch.

The console contains a DVD player, as opposed to the CD player of conventional consoles. Therefore, people can play DVD’s and CD’s on the console, as well as play games. Previews and demonstrations of games in development hint strongly at effects, graphics and (hopefully) gameplay as yet unexperienced on any games console or arcade platform. For example, the effect of ripples through water has been detailed to such a degree that it nearly impossible to distinguish from video footage of real water.

However, the line-up of games at the launch of the console has received mixed reviews, with the main game (Ridge Racer V) being a “safe” sequel to an established family of games, as opposed to being especially innovative or original. In addition, the launch of the console did not go without incident, as playing certain games on the console can lead to it not being able to play DVD’s, a problem currently being addressed by Sony.

The strategy for the Playstation II is heavily centred on online capabilities and opportunities. In 2001, Sony intends launching its own broadband network, through which Playstation II owners will be able to download games, movies and music. The extent to which this will occur is difficult to judge at the moment, as will be the time when it takes off in the UK. This is because the console manufacturers, and many of the overseas games manufacturers, tend to launch their hardware and software in Japan, then the US, then several months later in Europe. The current estimated date for the launch of the Playstation II in the UK is the end of September 2000.

Dreamcast

The Dreamcast looks likely to gain steady but unspectacular support over the next year. With conversions of several key arcade games taking place, and the US and European launch of Shenmue at some point in 2000, there are some positive things to look forward to. However, the online capabilities of the Dreamcast are currently disappointingly underused; in the UK, it is not yet possible to play a Dreamcast game against someone (remotely) elsewhere via the modem.

During 2000, several additional hardware devices, including a ZIP drive, digital camera and a microphone will be launched for the Dreamcast, thus increasing the non-gaming use of the console. In addition, Sega plan to allow games to be downloaded directly to the console, which theoretically will make games more affordable for the Dreamcast.

Several key games for the Dreamcast will emerge throughout the year, thus enabling it to have a viable future for at least 18 months to 2 years. However, competition from the Playstation II my prove particularly tough for the Dreamcast, and there is an increasing view that it will take a combination of several more classic arcade conversions and the full potential of the online capabilities being realised if the Dreamcast will survive well into the new century.

Dolphin

The Dolphin will be the next console to be launched by Nintendo. Various dates for its launch have been mentioned or rumoured, but it looks most likely to be launched at some point in 2001. With the continual problem of the lack of games for the Nintendo 64, there are some doubts as to how much of an impact the Dolphin can make on the games market, especially as the Playstation II will probably be an established platform at the time of the launch. There is no firm news on what, if any, online capabilities the Dolphin will possess.

However, Rare, producers of many of the top games for the Nintendo 64, are already hiring people to work on Dolphin related games. The involvement of Rare alone, developers of GoldenEye and Banjo Kazooie, will be a significant boost to the credibility and anticipation surrounding this particular console.

The X-Box

Microsoft has recently distributed press releases about its own entry into the games console arena, named the X-Box [15]. The X-Box is due to appear in the autumn of 2001 [16].

Details of the console or PC are currently still sketchy, though a brief technical specification has been released. The X-Box will try and combine the best of both worlds, in that it will provide a stable and homogenous environment for games developers to work on, while offering some of the practical non-game features of a PC, such as a hard drive.

With the backing of the wealth and marketing acumen of Microsoft, and the widespread interest shown in the gaming industry, the X-Box can be viewed as a potentially significant machine. Interestingly, Microsoft already have some experience in the games console market, as they produce Windows CE, the operating system installed on the Sega Dreamcast.

The PC

As the years move on, so the PC becomes more powerful and cheaper. Despite the problems about the lack of standardisation within PCs mentioned earlier in this article, the platform is still used heavily, and developed for, as a games machine.

An ad in the newspaper today from a well-known own-brand PC supplier gives details of a PC for sale for 1300 pounds. The package contains the usual peripherals, such as a colour scanner, printer and joystick. In addition, it includes a DVD drive, a 19 inch colour monitor, a TV tuner with teletext, decent loudspeakers for playing music and a video camera. Software allows you to watch TV programmes on the monitor, and record them onto the hard drive or a disc through an optional CD re-writer. In addition, there is a modem which, of course, allows you to download music, multimedia and other files…

Convergence

In the hardware described in the last section, we have an example of where the PC has converged with the television programme delivery and recording mechanism (making the video recorder partially redundant), and doubling as a CD and DVD player (also making those pieces of equipment redundant). While most of these features have some drawbacks as opposed to their stand-alone equivalents e.g. the DVD player in most PCs is not as high quality as most DVD players bought purely for that purpose, the “bundling” of this hardware is of some interest.

For example, a student may be watching an Open University programme on a window in the corner of their monitor. As the presenter explains the migratory wanderings of whales, the student could be manipulating a model of said whale, in a 3D visualisation plug-in, through a web browser. The student could record the programme onto disc and watch it later, pausing and rewinding at important moments.

A web search [17] then reveals new web sites and resources concerning the particular type of whale; the student could also listen to a CD of whale songs through the console CD player, and integrate some of the music, along with stills from the recorded TV programme, into a web-based report that she is writing. Finally, after the page is mounted on a web server running from the console, for light relief the student relaxes by downloading and playing a game of “Whale Attack”.

How much of the aforementioned scenario will become reality in the next few years, and how much of this reality will be caused by the push of the games console industry, is impossible to say. As well as the inevitable technical problems, there are also major problems regarding copyright and licencing, which may hinder “true” convergence (where material supplied in one format e.g. music on a DVD, can be converted and integrated into some other format or resource e.g. a web page or a programme).

While convergence will mean a reduction in the number of “gadgets” and pieces of hardware in the house, there could also be conflicts of interest. For example, in a typical household, young Johnny may want to play the latest Prodigy DVD, while Dad Bob wants to look for Web-based information on Rock Climbing. Meanwhile, Ruth may want to play Soul Calibur online against a friend in Barbados, while Jane may want to find and book a holiday in Norway. Clearly there is a situation where the ideal of one piece of hardware covering all of the “infotainment” options in the house is not enough; every person really needs their own converged system.

Issues for Higher Education

There are several issues directly or indirectly relating to the convergence of electronic information and gaming systems that UK Higher Education needs to consider. Three of these of particular relevance in the next year or two are briefly described below.

Use of the networks

The first and the most serious implication of the convergence of games consoles and contemporary electronic information service access “consoles” i.e. the PC, is that of the use of the networks. The use of the networks for online gaming is in no way new; to various extents, online gaming has been in existence in UK academia for some twenty years.

One UK University Librarian recently disclosed that 40 per cent of the internal university network traffic is suspected of being accountable to online and other games playing. Add to this potentially unethical uses e.g. online pornography, the large increase in down and up-loading mp3 music files (especially since Napster was created) and there is a situation where only a minority of the network traffic within a typical university could be either indirectly or directly work related!

One UK University Librarian recently disclosed that 40 per cent of the internal university network traffic is suspected of being accountable to online and other games playing. Add to this potentially unethical uses e.g. online pornography, the large increase in down and up-loading mp3 music files (especially since Napster was created) and there is a situation where only a minority of the network traffic within a typical university could be either indirectly or directly work related!

As online gaming becomes both more sophisticated in terms of the games (thus impacting on the amount of bandwidth used), and more popular in terms of the number of people who are aware and participate in this genre, so the amount of bandwidth eaten up by gaming will increase. How this will impact on JANET as a whole is difficult to predict over even the short term; however, several key online games releases this year, most notably Black and White by the Lionhead games house, will put the capabilities of the academic network to the test.

The use of esoteric browsers

Rightly or wrongly, the interfaces of many electronic information services are based around what looks acceptable through both Internet Explorer and Netscape. However, if large numbers of people start accessing and using these services and resources through new and alternative browsers, such as those available with newer online compliant consoles like the Dreamcast and the Playstation II, then problems may occur. For example, the Dreamcast browser, while adequate for email and basic web browsing, is not able to support (or absorb) some of the newer multimedia viewers and applications, thus rendering some web sites and web based resources either illegible or not at all.

With the advent of mobile phones and WAP (Wireless Application Protocol) based technologies, there may therefore be issues regarding what browsers are used to access resources and services. The conventional approach, of nearly all accesses being through variations of Netscape and Internet Explorer, may have to be revisited and re-examined, possibly in the next year and certainly within the next two. In addition, some browsers may encounter problems with authentication systems, such as those used to provide access to various bibliographic databases supported by the JISC. Having said that, there is a counter-argument that questions whether games consoles without the addition of large scale storage devices such as hard drives can be taken seriously as electronic information access points.

Location of access points

Four factors in particular are currently creating a rapid shift from networked access mostly occuring in a place of work such as an office, or a university computing laboratory, to the home or study room. It is possible that the use of WAP through mobile phones may soon produce a fifth factor, but this is unlikely in the next year or two. The four factors are:

- the advent of low-cost consoles that can provide online access (although only one, and with some limitations, does so at the moment). There is strong evidence that a substantial number of people who have bought the Dreamcast, especially those in the over 50’s age range, did so as it is by far the cheapest piece of hardware that can provide online access.

- the continuing fall in price of the PC.

- the continuing fall in the cost of online access, to the extent that several companies now offer free online access and phone charges, albeit usually with some conditions attached.

- the networking of the halls of residence in many Universities, thus offering students the ability to connect to the network in the privacy of their own room (essential for some non-work pursuits) with their own PC or console.

How this factors will affect the design of electronic information services and the networks through which these services will operate is unclear. What is clear is that the concept of the “Desktop PC at work” being by far the predominant method of accessing electronic information is becoming rapidly outdated; instead, the concept of “The user will access resources from the physical environment, such as the home, that is most comfortable and convenient for them” is fast becoming significant.

Here in the newly-formed Centre for Digital Library Research [18] in the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, the majority of staff own (and use) a games console or machine, be it a PC, Dreamcast, Playstation or Nintendo 64. We are quite keen to experiment with this technology, especially those consoles providing networked access such as the Dreamcast and the Playstation II, to see how they can impact on the use of electronic library services, resources and information. Through representation on the JISC Technology Change Group, we look forward to contributing our experiences to the JISC Strategy Working Group, and working with other stakeholders in this rapidly developing area; contact us if you are interested.

References

- Magnavox Odyssey information page

http://www.iaw.on.ca/~kaos/systems/Odyssey/ - The World of Spectrum

http://www.void.demon.nl/links.html - Ultimate

http://www.rare.co.uk/retro/ultimate/ - Atic Atac

http://www.rare.co.uk/retro/ultimate/aticatac/ - Jasper emulator, enabling people to play Spectrum games on their PC through their web browser

http://www.spectrum.lovely.net/ - BBC Micro retro page

http://www.arrgh.co.uk/hardware/bbc/index.html - Elite web site maintained by one of the original game authors

http://www.iancgbell.clara.net/clara.net/i/a/n/iancgbell/webspace/elite/ - Sony Playstation

http://www.playstation.com/ - Soul Calibur web site, including mpeg clips of some of the characters in exhibition mode

http://www.soulcalibur.com/ - Nintendo European Web site

http://www.nintendo.de/ - Sega Europe

http://194.176.201.21/english/se_frameset.htm - Game Boy Colour official Web site

http://www.nintendo.com/gb/ - Pokemon Web page

http://pokemon.com/games/redblue.html - BBC news item regarding the launch of the Playstation

http://news2.thls.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/world/asia%2Dpacific/newsid%5F665000/665765.stm - Microsoft X-box

http://www.xbox.com/ - BBC news item regarding the release of the X-box

http://news2.thls.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/business/newsid%5F671000/671973.stm - A successful search for quality Internet-based resources concerning whales

http://link.bubl.ac.uk/ISC8041/ - CDLR: Centre for Digital Library Research

http://cdlr.strath.ac.uk/

Author Details

| John Kirriemuir, Funding and Public Relations Co-ordinator, Centre for Digital Library Research, Andersonian Library, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow Email: john.kirriemuir@strath.ac.uk |

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Jane Barton, Abdul Jabbar, Bob Kemp and Ruth Wilson from the Centre for Digital Library Research, University of Strathclyde, as well as Martin Hamilton from the University of Loughborough, for useful comments that helped to shape and direct this article.