Cultural Heritage Online: The Challenge of Accessibility and Preservation

Hosting a conference next to Florence's Uffizi Gallery and the sculpture-studded Piazza dei Signori is not a bad place for a conference on preservation and access to digital cultural heritage. And the condition of the courtyards, palaces, frescoes around the city show that someone has done a pretty good job at old-style preservation - give or take the occasional flood. But could the same be said of the preservation of digital culture being created in the present?

Such were the questions being debated in Florence at Cultural Heritage online: the challenges of accessibility and preservation, held over 14-15 December 2006, and supported by both UNESCO and the European Commission [1].

As with many European conferences, the number of initiatives, projects, Web sites and outcomes on show was both impressive and overwhelming. Pat Manson, Head of Unit 'Learning and cultural heritage' within the EU's Information Society Technologies division, partially explained why this was the case. The EU has recognised the value of digitised culture; indeed the past Framework Programme 6 and the forthcoming Framework Programme 7 both call for preservation issues to be tackled within the digital library and content strand. Moreover, broader EU targets for digitisation are creating more and more digital content, and with each silent click of the digital camera, the related preservation issues become more pressing.

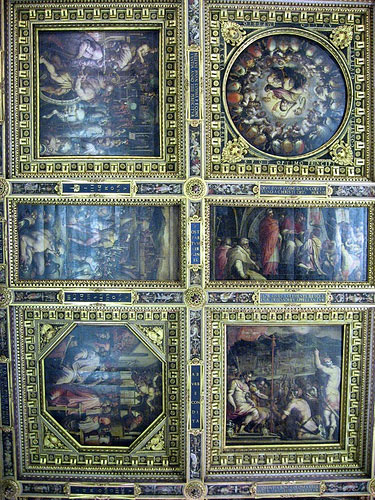

Figure 1: Dinner was held in the splendid Palazzo Medici-Riccardi.

This is a seventeenth-century ceiling by Luca Giordano.

So we heard, amongst many others, Catherine Lupovici speaking on Web archiving at the Bibliothèque nationale de France; Vito Capellini on new advances in invisible watermarking; Philippe Poncin on the colossal audio-video collection at the Institut National de l'Audioviseul and Rowena Loverance on the dilemmas museums face when deciding whether to preserve user-generated content.

A couple of speakers went into more technical detail. The presentation of Giovanni Bergamin, from the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale of Florence, was particularly interesting. He outlined the Digital Stacks Project, and the hardware solutions chosen for its data management. Taking the lead from Google and the Internet Archive, the Florence team eschewed vendor-specific servers and instead used a rack of desktop PCs for their file store. Being able to incorporate around 2TB per PC, the team just needed a few computers to provide preservation, access and back-up services, all without being tied to a specific seller. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, changing hardware in case of failure was a reasonably straightforward task.

Borje Justrell, of the Riksarkivet (National Archives), Stockholm, relayed results of a Swedish survey into costs of digital preservation. The point was forcefully made that the future will see falling hardware costs; rather it is support and service costs for digital preservation that will begin to bite into libraries' and archives' budgets.

Figure 2: The opening presentations were held in the Salone del Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio.

This is a detail of the ceiling, with paintings by Giorgio Vasari.

But the general tenor of the presentations was less about the technical issues than the broader strategic ones. The understanding is quickly growing that just as the Web is distributed, so are the expertise, approaches and practices that manage cultural material on the Web. Building shared networks of collaboration between different venues is an essential part of developing successful infrastructures. Elizabeth Dulabahan's case study on Library of Congress work, and in particular its development of the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program, showed such infrastructures were just as essential on the other side of the Atlantic. Not only could such a programme allow for planned content building, but it could also experiment with models for sharing preservation tasks and costs, as well as sharing expertise in developing tools and technologies. Other national perspectives were introduced - Ute Schwens reviewed three years of Germany's nestor Project, while Paolo Buonora spoke of the need for greater thinking at a national level in Italy. EU-wide projects such as Caspar, Planets and Kopal were also introduced.

Despite the title of the conference, preservation was more of a buzzword than accessibility, but there were two forceful presentations related to access and user experience. Opening speaker Paolo Galluzzi pointed to the development of Web 2.0 technologies and how many digitisation programmes are ignoring its potential; much more needs to be done to provide meaningful connections between different collections, certainly something much more effective than collections of hyperlinks.

One of the other keynote speakers, Seamus Ross, pointed out the need for far greater understanding of user needs and user behaviour. Far too often thinking on online digital culture is based on poorly-handled user surveys, the exaggerated importance of quantitative statistics and anecdotal 'evidence'. In general, he continued, there is a lack of clear methodologies for understanding user needs. Only once more robust methodologies are developed will we have a much better understanding of users' needs, and how that will affect long-term preservation.

References

- Conference abstracts are available from http://www.rinascimento-digitale.it/index.php?SEZ=412