Preserving Local Archival Heritage for Ongoing Accessibility

Digital preservation is an area which is pervasive and challenging for many sectors – it impinges on the landscape from high-level business and e-government to an individual's personal digital memories. One sector where the challenges of preservation and long-term access to resources are well rehearsed is within the archives sector. There has been innovative research within the archives community including the Paradigm [1] and the DARP [2] projects. The initiative described in this article focuses on the local authority archives sector and is an outcome of collaborative work from the authors, the Digital Preservation Coalition (DPC) [3] and The National Archives (TNA) [4]. We discuss the drivers for the survey, outline the survey findings, and highlight the main themes found from both the survey and a consultative meeting which took place with representatives from the sector as a follow-up. The article concludes with next steps to keep the momentum ongoing.

The Survey

The aim of the survey (available from the DPC Web site) was to collect a snapshot of current preparedness for digital preservation within the local authority archive sector. Local authority archive services collect, preserve and make available records relating to their geographical area, not only from their parent body, but also from other local organisations, families and individuals. Invitations to respond to the online questionnaire were issued via the Association of Chief Archivists in Local Government (ACALG) in England and Wales, the Archivists of Scottish Local Authorities Working Group (ASLAWG), and the Local Government group of the Records Management Society. ACALG and ASLAWG are the professional bodies for the heads of local authority archive services in England, Wales and Scotland respectively. The survey was available throughout September 2008.

Responses

38 responses to the survey were received. Regional analysis showed varied levels of uptake: no responses were received from two English regions, and only one from Wales. Response rate cannot of course be determined due to the wide distribution of the survey but responses were received from 36% of the ACALG membership polled. The majority of respondents were also archivists, or records managers working directly within an archive service organisational structure. 30 of the identifiable responses came from Archive Services in England and Wales, about 24% of the 126 services which National Advisory Services [5] supports, and six of the responses came from services in Scotland.

Digital Preservation Planning

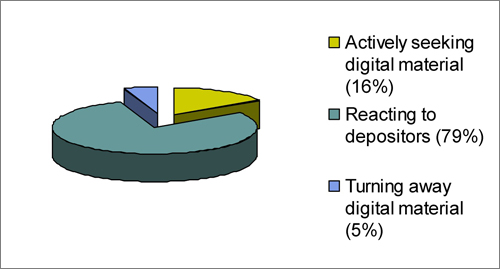

Most respondents (79%) chose to describe their service as 'reacting to depositors' when it came to digital preservation planning, although several services reported moving towards a more active position. Some respondents felt that it was inappropriate to encourage deposit until they had policy or procedures in place for handling digital material. However only two respondents (5%) actually claimed to be turning away digital material.

Figure 1: Digital Preservation Planning in Local Authority Archive Services

One respondent commented that 'digital curation is currently re-active, at an experimental stage with no resources allocated to a co-ordinated effort in this area', and this would seem to describe many services' present position. Significantly, very few services actually claimed to be turning away digital material.

Practical Digital Preservation

The survey revealed a lack of knowledge about the digital material that local authority archive services already hold. Respondents were asked to include digitised surrogate material, and in some cases this appears to be the only digital material the service holds. But many respondents had difficulty assessing quantities simply because digital material is often 'scattered through various accessions', and on different kinds of storage media – over four fifths of respondents use CDs or DVDs for at least some of their digital storage.

A wide variety of file formats were represented in the responses. Still image formats – jpeg and tiff (plus pdf) – are the most frequently held digital file types; presumably because many local authority archive services have invested heavily in recent years in digitisation initiatives. Office-type documents were also frequently reported, particularly Word, Excel and Access, with a fair smattering too of older, obsolete formats, including Lotus 1-2-3, Publisher 2, and Claris Filemaker. There was some evidence of niche proprietary formats, such as Kodak Photo CD and the family history software export format, Gedcom. Many services also held digital moving image and sound collections, and there were two reported instances of CAD/CAM (Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing) designs. This variety of reported file types comes as no surprise given the de facto mixed collecting remit of UK local authority archive services.

Access to Digital Archives

The mission of local archives services is to provide ongoing accessibility to the preserved content for current and future users. Very few services appear to have set about addressing this issue for digital archives; at present, 68% have to rely on ad hoc arrangements involving CDs or memory sticks accessed on site in the searchroom. Although a few services are able to provide online access from server storage or a tape library, they too still expect users to visit the service in person to view records. Eight respondents (26%) claimed to be providing access via the Internet, although in practice this appears to refer to galleries of digitised images rather than a comprehensive storage and access architecture for all digital material.

Storage and Handling

Asked how digital records are handled when they first come in to the archive service, 42% of respondents admitted they take no action and digital records are simply stored on their original transfer media in the archive service strongroom. On a more positive note, half of respondents would at least check to see that they could open the files, and 45% copy the files onto different media, usually to server storage. It was clear that several services aspire to implement more managed procedures in the near future, although many also have a backlog of older material to work through. Some services are beginning to implement procedural documentation for digital ingest, and some are already using automated tools, such as DROID [6]. Generally, the impression was that obtaining dedicated server storage for digital preservation was often the hardest challenge, particularly for digital archives received from external private depositors, which raises security concerns for IT departments. Sometimes digital storage capacity is chargeable.

Several services saw a need for guidelines or discussions with depositors to collect metadata about the digital records being deposited. Four services have documentation in the shape of digital accessions forms which they ask depositors to complete, although generally this kind of manual metadata collection was low. One respondent commented that depositors themselves often lack the technical knowledge which is required to complete such a form, and favoured the use of automated metadata collection tools to circumvent this problem.

At a high policy level, 18 respondents (47%) reported that they have some kind of digital preservation policy in place, and several more claimed work was in progress or included in business plans for 2008 or 2009. Evidently there is documentation already available which could usefully be shared across the sector.

Digital Preservation Awareness

Awareness of digital preservation R&D activity was generally low. Several respondents commented along the lines that 'a lot of the work on digital preservation is very high level and difficult to place in a "normal" archival setting' and felt that as such this 'obstructed learning, awareness and progress'. This may simply reflect the fact that few services have yet to prioritise work on digital preservation – at least beyond sketching out a high-level policy – although the lack of knowledge of existing 'wins' within the sector was also significant.

The Digital Preservation Coalition, was well known – by 74% of respondents, but this contrasts markedly with awareness of digital preservation research projects – even The National Archives' initiatives, Seamless Flow [7] and the Digital Continuity Project [8] were recognised by fewer than half of respondents, and beyond these two projects only the UK Web Archiving Consortium [9] scored recognition levels above 40%. Disappointingly, the East of England Digital Archive Regional Pilot (DARP) [2] and Paradigm projects [1], also registered low levels of awareness, at 37% (14 respondents) and 34% (13 respondents) respectively. Both these projects challenge the perception that current digital preservation research is poorly aligned to the local archives context.

Gaps and Barriers to Digital Preservation

Given the low levels of awareness of current digital preservation work, it is unsurprising if some respondents struggled to conceptualise what a digital preservation programme might 'look like' within their archive service. Some respondents appeared to be muddling up digitisation – the creation of digital surrogates – with digital preservation – the curation of those digital objects.

The main barriers that were articulated can be broadly grouped into three areas:

- Cultural (organisation, political issues, awareness, external partnerships/relations and motivation)

- Resource (time, costs, funding, storage)

- Skills gap (training, competencies, IT)

Funding was identified as the key barrier which will have an adverse effect on the other problematic issues down the line. These findings were similar to a survey that was conducted by the DPC earlier in 2008 as a follow-up study to the 2006 Mind the Gap report [10].

Professional Relationships

87% of respondents reported having a records manager within the authority. Most services have good working relationships with their records managers, although only about half (47%, 18 out of 31) of archive services are involved in the implementation of EDRMS (Electronic Document and Records Management System) within their authority. There was no obvious correlation between archive service involvement in EDRMS roll-out and progress in digital preservation, although in several cases digital preservation has been included within the remit of the records manager.

In contrast to the generally good relations between archivists and records managers, working relationships with ICT support services were sometimes characterised as poor, even antagonistic. Whilst 71% claimed to have access to ICT project management expertise, and 52% to software developer expertise, in many cases ICT development time is subject to a competitive bidding process, or is outsourced or otherwise chargeable. Few services have been able to include funding for digital preservation activities in the archive service budget, and even fewer have experience of large-scale ICT infrastructure development projects of the kind which might be required to meet the digital collecting aspirations outlined in responses to the survey.

How Does the Sector See the Future?

There was little consensus here, either as regards potential organisational models, or future collection patterns. In-house and regional repositories were the most popular choices for the organisational model, but as many people voted against in-house repositories as were in favour of them. Only outsourcing to a private supplier was truly unpopular, with 11 of 38 respondents considering it not viable and a further eight marking it as the least preferred option.

As regards future collecting, it would seem most respondents favour continuity of the existing mixed public/private collecting pattern. Unsurprisingly, 89% of respondents felt that preserving the digital records of local authorities is very important. However 71% also gave top priority ('very important') to the records of small local 'official' organisations, such as schools and parish councils, and 63% to the records of religious organisations. At least four fifths of respondents also regarded it as relatively or very important that local authority archive services continue to collect material created by external organisations, such as businesses, charities, local societies and private individuals. There was some awareness that this may be problematic, given the lack of control over record creation that an external depositor relationship implies.

Skills and Training

This question was completed by 89% of respondents and all agreed that there was a skills gap which needed addressing. The suggestions ranged from softer, more generic skills, such as project management and negotiation, through to basic generic ICT skills, as well as more detailed courses addressing specific issues, for example, advice on file formats, migration strategies and digital accessioning. From some respondents there was an acknowledgment that an array of skills was required depending on the role and responsibilities of the specific staff within the archives.

Suggestions about the mode and type of delivery varied from formal education, to customised in–house training, or online learning, through to placements and job shadowing.

A recurrent theme was the alignment of traditional and emerging competencies and skills – to support people's confidence and to address the skills shortage. There was a call for practical training addressing specific curation processes, and for the sharing of expertise collaboratively across the community. It is important that staff currently in post have the opportunity to address the acquisition of skills while the same is true in the case of archives professionals in training. In future, all local authority archive staff should feel comfortable dealing with digital material. However, there will be a need for some specialists who are able to resolve more complex issues. There are some local specialists emerging already, as practitioners with an interest in this area develop skills and expertise. The sharing of that expertise was highlighted at the open consultation day mentioned below.

All of the above is predicated on the assumption that there is funding for any of this activity. From the responses received there is certainly no budget at the level of individual local authorities.

The Open Consultation Day

In mid-November 2008 the National Archives invited heads of archive services in England and Wales to a consultative event designed to: promote awareness of digital preservation in general; highlight the survey and other recent initiatives in England and Wales, and; help local archives make progress with practical measures to achieve digital preservation. Over 40 invitees attended and the day provided presentations from a range of stakeholders together with planned discussions. The afternoon session focused on the outcomes of the survey and the delegates were divided into four syndicate groups to address some high-level questions.

The topics which the groups were asked to consider were the major themes which emerged from the survey, namely: organisational models, funding, partnerships and advocacy. There was lively debate among all groups and at the end of the session the facilitators reported on their groups' deliberations. Two groups were asked to consider organisational models and professional partnerships. The remaining two groups looked at funding and advocacy issues. This provided some level of validation and identified areas of consensus between the groups.

Feedback from the Syndicate Groups

Not unexpectedly there was overlap between the issues raised amongst the groups. For those groups considering organisational models and partnerships, the recurrent message was that local authorities' archives would work more happily in partnership with a national body rather than with an outsourced commercial player. To progress digital preservation within the sector there would need to be joint ownership and 'buy-in' from the authority at all levels i.e. from the Chief Executive to the IT department. It was felt that authorities need to address these issues urgently or they will fail to meet their legal compliance responsibilities.

Advocacy was a key issue both within and external to the authority. It was acknowledged that there was a complex set of relationships amongst the stakeholders, many of whom talked in different languages and had various expectations and drivers. The core issues needed to be defined and articulated in an accessible manner for all players.

Reflecting on the optimum organisational model, a local in-house solution was attractive with a strengthening of shared expertise and knowledge. The risks though were of under-achieving due to local constraints, inequalities across services and differences in the positioning of archive services within the organisational structure. The sharing of expertise was picked up in the suggestion of a 'community of the willing'. Another suggestion was for a collaborative approach to the development and implementation of a digital preservation framework, inspired by the Australasian Digital Recordkeeping Initiative [12]. Individual archive services could then choose to work on specific projects matching this overall strategy, incorporating the work into their own corporate business planning but sharing the results with the wider archives community.

An outsourced solution would necessitate standards and guidance in selecting contractors. The concept of a trusted digital repository would be welcomed using tools such as DRAMBORA [13] and PLATTER [14]. Delegates were more comfortable with the notion of outsourcing to a public sector organisation, for example TNA or the British Library, rather than a commercial organisation. It was felt that other public bodies would have the same value system and sense of intellectual control as the archivists.

In the opinion of the groups looking at advocacy and funding, the essential issue was to ensure that any initiatives were mapped onto the business drivers of the authority. If information is recognised as a key asset by the Audit Commission it was felt this would have leverage with the major local players. With regard to funding, successful pilot projects within the local authority archives sector would act as exemplars of good practice, help to contextualise the issues, and demonstrate the value of investment in the digital preservation area.

Both groups also felt that there was potential in working with archive colleagues from other sectors, particularly those from Higher Education and Museums. Another strategy which might have leverage was to try and source funding from the wider local authority budget e.g. the EDRM, pursuing the compliance and Information Assurance angle.

There was speculation about the possibility of establishing a funding pot from grant-giving organisations, as has been established by The National Archives and various organisations in order to tackle cataloguing backlogs.

There was some concern expressed about what the future role of the local authority archivists would be if digital preservation was outsourced. Would this affect their relationships with local depositors? It was felt that their future role within the outsourcing scenario would be to act as gatekeepers to the material; selection, appraisal and rights management expertise and skills would still be needed.

A plenary session at the end of the day rounded up these ideas and the day ended on a positive note. The challenge now would be to keep the momentum going and to follow up on the day's actions.

Next Steps

The next steps which were supported by those at the consultation event are summarised below:

- To hold regular meetings to maintain momentum. It was agreed that the agenda of the next meeting would include showcasing some concrete developments and practical projects for delegates.

- There was an appetite to continue to work with the DPC and TNA to promote wider co-operation across the archives sector.

- There was a need for continued advocacy at a local level, particularly drawing on continuity from records management work in local government.

- Scalability was seen as a crucial issue to be addressed – starting with small, prototype projects and building upwards.

- To attempt to establish grant funding for digital preservation work in the local government sector.

Conclusion

The work to date has not perhaps uncovered any great surprises. However the big win has been that the conversations are happening and the sector is motivated. The key issues to emerge from the survey results: funding, organisational models, partnerships and advocacy, were echoed by the delegates of the consultation day. So the community has a clear message, from its own constituents, where effort and resources should be concentrated in the first instance.

The response rate also indicates that the sector needs to engage with the unengaged, and ensure that future work includes those who did not respond to the survey or attend the consultation event. There are many other competing pressures on archive services' time and resources, and part of the advocacy strand needs to be about defining compelling arguments and business cases for prioritising digital preservation. In the reality of competing priorities in a sector with limited resources, lack of engagement with digital preservation is not necessarily a sign of uninterest. It is perhaps a consequence of the crowded busy landscape in which archivists are operating as they juggle an ever-increasing number of demands.

There are already exemplars of good practice within the local authority archives sector, and the beginnings of a 'community of the willing'. So it is now up to the community to maintain this momentum as well as the confidence to take these initial steps forward with all stakeholders; in this way they can assure ongoing accessibility to local archival heritage for future users of such resources.

References

- Paradigm Web site http://www.paradigm.ac.uk/

- DARP2 Report http://www.mlaeastofengland.org.uk/_uploads/documents/DARP2Report.pdf

- DPC Web site http://www.dpconline.org

- The National Archives (TNA) Web site http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

- TNA: Services for professionals | National Advisory Services Web site http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/archives/

- DROID Web site http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/aboutapps/fileformat/pdf/automatic_format_identification.pdf

- Seamless Flow Web site http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/electronicrecords/seamless_flow/default.htm

- Digital Continuity Web site http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/electronicrecords/digitalcontinuity/default.htm

- UKWAC Web site http://www.webarchive.org.uk/

- Mind the Gap report Web site http://www.dpconline.org/graphics/reports/mindthegap.html

- Australasian Digital Recordkeeping Initiative Web site http://www.adri.gov.au

- DRAMBORA Web site http://www.repositoryaudit.eu/

- PLATTER Web site http://www.digitalpreservationeurope.eu/platter/