Institutional Repositories for Creative and Applied Arts Research: The Kultur Project

Those involved in Higher Education (HE) may have started to sense the approach of Institutional Repositories (IRs). Leaving aside the unfortunate nomenclature, IRs are becoming a fact of life in many educational institutions. The Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) has invested £14million in the Repositories and Preservation Programme [1] and the recent Repositories and Preservation Programme Meeting in Birmingham [2] celebrated the end of over 40 individual repository projects under the Start Up and Enhancement [3] strand. However this does not signify the end but really only the beginning for many institutions in managing their own IR.

In 2006 Sally Rumsey clearly pointed out the advantages and the purpose of IRs for HE [4]. One of the main drivers for any HE institution is the promise of a system that can manage and promote the research activity of their academics. Anyone who has experienced the recent Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) and trembles in anticipation of its replacement Research Evaluation Framework (REF) will concur with Harnard et al when in 2003 they stated:

'The RAE costs a great deal of time and energy to prepare and assess, for both universities and assessors (time and energy that could be better used to actually do research, rather than preparing and assessing RAE returns).' [5]

Yet any examination of this burgeoning IR landscape will not fail to identify the meagre showing of the arts and humanities disciplines. There are very few IRs for the arts but Daisy Abbott and Sheila Anderson [6] state that digital content for the arts and humanities is proportionally higher than its share of the education market. Daisy Abbott does go on to suggest that:

'the arts and humanities, whilst slow to grasp the e-prints open access agenda, instead prefer to embrace the digitisation and dissemination of primary sources, most particularly image collections and textual sources.' [7]

It is this conflict that the JISC Kultur Project has grappled with in creating a transferable model of an IR for the creative and applied arts.

The Partners

Kultur was a two-year project that finished in March 2009 and brought together the expertise and experience of University of Southampton (UoS), University for the Creative Arts (UCA), University for the Arts London (UAL) and the Visual Arts Data Service (VADS). UoS had not only supplied considerable experience of IRs but is responsible for the Eprints software we used and developed on the project; and in Winchester School of Art we had a research community that could contribute to the project. Further art communities were supplied by UCA and UAL. UCA has 5 five constituent art colleges situated at Canterbury, Epsom, Farnham, Maidstone and Rochester. UAL is comprised of Camberwell College of Arts, Central Saint Martins, Chelsea College of Art and Design, London College of Communication, London College of Fashion and Wimbledon College of Arts. Between them they cover all areas of art, design and the applied arts. In fact if it is not studied at these colleges 'it ain't art!'.

VADS is an online visual resource for the art community and has numerous digitised collections. It was an obvious choice in the formation of a partnership since it could supply a great deal of expertise and advice in many areas including metadata and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR). Such a collaborative project raised obvious but vital issues. The main issue was communication; each project officer was located at a different site with the project manager and Eprints developer again at a different location. Regular meetings were scheduled and full use was made of email, Google docs and belatedly Skype. Good working relationships were built up and served to illustrate the advantages of collaborating with staff from similar and different institutions.

The Process

Our first goal was to scope our individual institutions and produce an environmental assessment. We examined the academic and research structures of our institutions and tried to ascertain what research was produced. Part of this assessment was to discover what research was already available digitally and online. This was done by combing through our institutions' Web sites and staff profiles and looking for links to work or actual works that are already accessible over the Web. This allowed us to identify who to contact in order to collect work for the demonstrator repository that we had set up. The assessment also highlighted the fact that there was a large number of part-time staff that was also research-active. The research practices of this group would also need to be addressed as part of the project.

We decided to use an online survey [8] to help in the development of the demonstrator and the project. The address for this was distributed via staff email, posted on institutions' intranets and included in the weekly email newsletter. We were aware of the low number of responses such online surveys typically attracted. Add to that the fact that a lot of part-time research staff either did not have university email accounts or did not regularly check them, and we also resolved to post paper copies (with the online survey address) in staff pigeon holes and in the library. The response was still low but we felt we had enough responses to work with [9]. Using those responses, we asked certain researchers if we could conduct one-to-one interviews with them. In total we interviewed 15 researchers across all 3 institutions, making sure that we covered as many of the disciplines as we could [10]. All our findings fed back into the development of the demonstrator repository. The survey and interviews also doubled up as modes of advocacy for the project. Advocacy was also undertaken in various ways. We spoke formally and informally with a number of staff. Presentations were given to research centres, research offices, library staff and various management teams. Lots of coffee was consumed as we tried to identify members of staff who would be interested in the project and persuaded them to provide us with work for the demonstrator. Presentations were given at the Arlis (Art Libraries Society) Conference and OR08 (Open Repositories Conference). Various 'events' around the institutions were also attended such as private views, book launches and talks, which offered the advantages of having researchers present and more relaxed opportunities to find out about them and promote the repository. Once we had a more developed demonstrator repository we conducted some usability tests which again fed back into adding new features, removing old ones or tweaking others. Approximately four months before the end of the project, the demonstrator repository split and UAL and UCA each hosted their own repository. While we all still worked together on major issues such as copyright and IPR, we were also involved in embedding the repositories within our own institutions and tackling such matters as IT, institutional policies and branding.

What's the Problem?

The majority of IRs have handled and dealt with the traditional research output of articles which have often been in the standard pdf format. Art research also has a considerable amount of articles but the Kultur Project focused on multimedia and how to depict this in a coherent and valuable way. There is also considerable debate within art academia around the whole notion of art and research. Art research is often practice-based and it has been felt by certain sections of the community that the methods employed to measure its success as research, e.g. the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE), are really only suitable for more scientific disciplines [11][12]. Although the skills of the Kultur Project team were considerable, we did not seek to solve this debate, but rather, used it to understand and navigate our way through certain barriers to the project.

The best way to illustrate how we have tried to address and cater to the needs of our researchers is to examine our repository and explain how we reached such conclusions and why. Originally all 3 institutions shared a demonstrator repository which we populated with various pieces of work and pulled apart and put back together again in various guises with varying degrees of success. Since January 2009 UAL and UCA were given their own repositories and the work that was in the demonstrator was moved according to its provenance. Access to the demonstrator repository is no longer available so I will, in the main, be using images from, and referring to, UAL's repository UAL Research Online. However, I will also be using UCA's repository (currently unnamed). Work from Winchester School of Art has been returned to the University of Southampton repository, where they are in the process of implementing the enhancements developed as part of the project.

Does My 'Art' Look Good in This?

Bad pun aside, the visual aspect of the repository loomed large in all our minds during the project, especially in the early stages. We are dealing with an arts community which by definition has a highly 'tuned' sense of the visual aesthetic. Concerns about the design of the site were voiced in our survey and how such a design would reflect upon their actual work:

"Really worried that the interface (from a 'customer' perspective, NOT super-user) would poorly reflect the work within." Survey respondent 1 "... to be somehow more visual. Work to be represented by thumbnails" Survey respondent 2

If you compare Figure 1 with Figure 2 you can see that there is a considerable difference between the original version and that with which the project finished.

Figure 1: Original Kultur Demonstrator Home Page

Figure 2: UAL Research Online Home Page

The most striking difference is the use of images throughout the site. In many ways it resembles more a 'Web site' than a typical 'institutional repository'. The idea was to promote the range of work from the institution and this was best served by having a series of random images pulled from records and then displayed on the front page. The strip below the main image is the other images that will be displayed while on this page, with each image changing every 10 seconds and the whole series of images changing every 15 minutes. This visual aspect is continued in the right-hand column where we have thumbnails representing the 'latest items'.

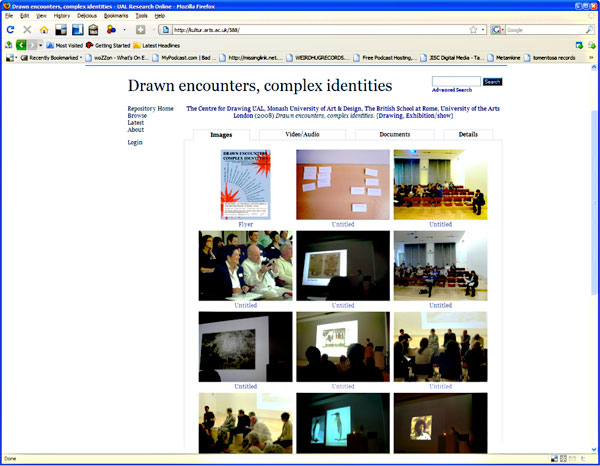

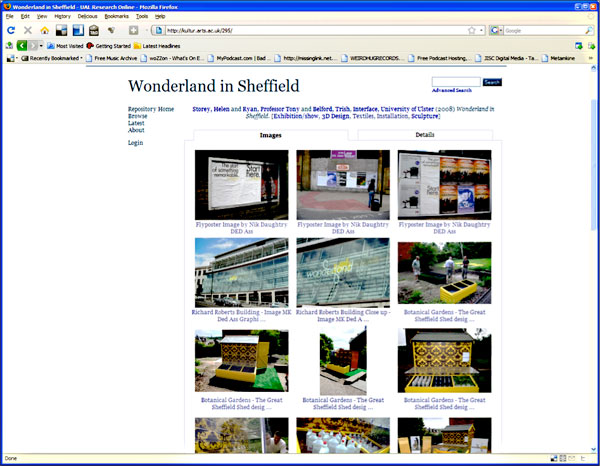

In the actual record of the work the visual aspect is emphasised above other information including the metadata (what we have called 'details'). What became very clear from our survey and interviews, as well as our own personal knowledge, was that records for arts research would often have multiple items. Documentation of a particular piece of arts research could often involve digital images, audio or video, posters, articles or text. All would relate directly to the piece of research and illustrate a different aspect. Documentation of such research becomes extremely important, particularly where the work may be temporary, such as an exhibition. In Figure 3 we have a record for a conference which held a number of different items.

Figure 3: Item Record With Tabs

The item record presents a maximum of 4 tabs with the 'images' tab as lead. This is then followed by the tabs 'video/audio', 'documents' and finally 'details'. There are in fact 19 'images' in this record which does involve scrolling down to view them all. The size and number of images to be displayed on a line was a source of continual debate once we discovered that particular research outputs could have over 100 images associated with them. Our ideal when having a large number of images was to have a maximum of five on a line, but of a size that would still be meaningful. When using the site, one of our interviewees stated that scrolling was preferable to viewing tiny images. At UAL this 'debate' was curtailed by the UAL Web site template which would only allow a maximum of three before the images became too small to view.

Another issue that this particular record raised was that of copyright. It arose in respect of the conference jointly held by UAL, Monash University of Art & Design and The British School at Rome. The delegates and contributors were all from these institutions. Before the conference actually began, I got in touch with the organisers at UAL and asked them to gain clearance from each of the contributors to include their images, presentations and articles, as well as obtaining their permission to use their 'likeness' online. This was achieved in the majority of cases. However, I was contacted by the organisers after they had sent me video of the conference to ask me not to include it since they were concerned that there might be footage of a sensitive nature or permissions that they had not cleared, and that they would need to edit it first. For the project this pointed out that the repository would need to be involved or at least provide consistent and clear advice at the outset of such a conference. We had been lucky to speak to them beforehand, but a lot of the work that we handled over the development period of the project had obviously been completed retrospectively and there had been little or no notion of rights clearance.

In our survey, 48% of respondents had rated their knowledge of copyright as moderate to high; more respondents had rated their knowledge as very high than those who had rated it as low. Though this may correspond more closely with another result of our survey: copyright and how their work could be appropriated proved to be the chief concern of respondents regarding the placement of their work online. It is hard to draw a definite conclusion from this, but arguably researchers are very aware of their own copyright when they themselves have produced the work, but become increasingly unsure and uneasy once others are involved or have collaborated with them.

Not only does collaborative work figure highly in the majority of our researchers' practice but also other accreditation needs to be taken into account. A researcher may often employ the skills of others in the documentation of their work. We found that a certain amount of work provided to us would often contain images taken by a photographer not the specific researcher. So, while not strictly a collaboration, there is a need at the least to credit such photographers in this example and, where necessary, clear the rights to use their photos. Again our survey indicated that respondents who already had their work online tended to possess a better knowledge of copyright than those who did not. This was often borne out by our initial populating of the demonstrator repository where we looked for staff who had their own Web sites in order to identify work for the demonstrator. Staff who had maintained their own site for a while would be precise in crediting all who had been involved in their work.

To depict and represent a possible situation of multiple rights holders or even multiple accreditations, the demonstrator allowed us to place information regarding each image or item alongside that item (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Record displaying different photographer accreditation

Video/Audio:

Moving image and audio is a widely used medium within the arts community. It may be used simply as documentation of a specific event such as a conference or a performance, or it may be the actual research practice itself, such as a video work. Each has its own, though not mutually exclusive, requirements. As discussed earlier, film of events such as conferences will need the permission of those involved; this can also be the case with film of theatre performances which may well involve multiple rights holders. This can range from the author of the work performed, to the music used, to each of the actors in the performance. There also arises within such documentation the 'unsatisfactoriness of reproduction' where the video or film cannot truly convey what happened in a 'live' performance. However documentation is still needed, and some researchers overcome this by providing extra pieces of documentary evidence to create a more 'rounded' picture of the work. Another issue for practitioners working with video or sound art relates to the viewing context - how and where the work is experienced - as remarked upon with 'performance' work.

'... I am sometimes uncomfortable about the fact that the resultant work may only be heard on lower-resolution PC speakers and about the fact that to listen to/engage with work on a PC that is also used for a whole host of other activities may rob that work of a certain specialness.' Respondent 3 (Kultur Survey)

Such reservations also apply where the work was originally part of a multi-screen installation or relies on physical size to produce the intended effect. We are also faced with the reality of work that is being produced that is at a much higher resolution, for researchers now working with HD (High Definition) film. Researchers may then be reluctant to provide us with their actual video work. One researcher from UCA decided to provide us with only a sample of the work in a smaller resolution, but enough to give a flavour of that work. This alongside textual information or documentation could help to overcome this reticence.

File Formats

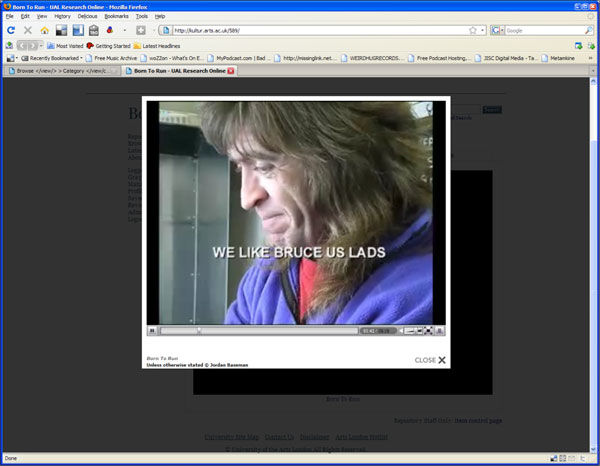

File formats and file size was a concern throughout the project and one that we opted to leave to the individual institutions since it fell to them to define the limits of what they could accept. As a project we wanted to encourage as much work into our demonstrator as we could, and also subsequently discover what limits and stresses applied to the Eprints software. The actual range of formats provided was not enormous and tended to correspond with our expectations. We dealt with such common formats as mov, jpeg, tiff, ping, photoshop, quicktime, avi, flash, windows media, mp3, wav. We were eventually able to deal with and represent them all. In order to stream videos, we converted to flash for our video player (Figure 5). However the actual format itself is preserved, so if the researcher permits, the original format can be downloaded. As to file size, there were some problems with uploading large video files to the demonstrator, though this difficulty was resolved with a larger server.

One request from a group of researchers was to have the ability to use FTP to upload large files; unfortunately we did not have enough time to explore this in depth as part of the project, although at UAL it is an issue that will be investigated.

Figure 5: Streaming video player

The quality of the images and video which we were permitted to 'grab' from researchers sites was variable. Much depended on researchers' attitudes towards protecting their 'copyright'. While all researchers wanted to promote their own research and raise their own profile, they were also anxious that the repository did not interfere with any commercial opportunities that could arise from their own practice. This was particularly evident from photographers and video artists. One researcher had sold his video work and part of the agreement was that the work would not be available elsewhere. There were also concerns that if high-quality files were available for download, then they could be used to print out high-quality prints of the work. On the other hand, researchers were encouraged by the fact that high-quality images could be stored in the repository and yet be restricted to those whom the researcher elected. This type of control is allowed in the repository through the Eprints 'request a copy' button (Figure 6). This option was an advantage for researchers when promoting work to galleries since it allowed galleries in different cities to access high-quality images and thus could help in gaining exhibition opportunities. This practical approach was appreciated by a research team which welcomed the access to its own high-quality images when working away from its base, while secure in the knowledge that access was not extended to others outside the team.

Figure 6: Request a copy button

Metadata

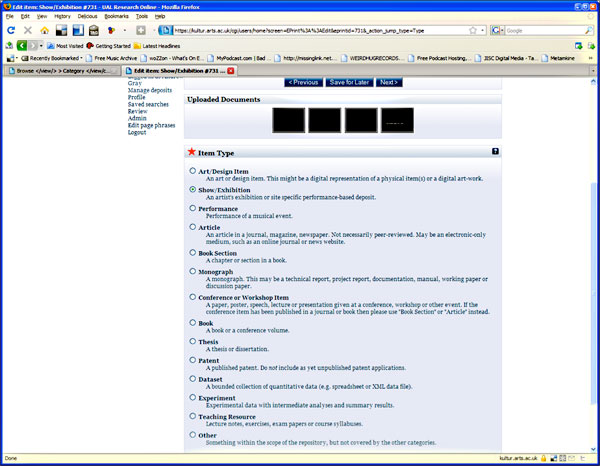

One of the significant differences between art research, as remarked earlier, is that of multiple items, multiple rights and multimedia. As we worked through the project the metadata were reworked on numerous occasions. Trying to produce a deposit form that was consistent, clear and which took into account the varying disciplines proved quite a task. After much to-ing and fro-ing we decided on the set of 'item types' which determined which metadata fields were presented (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Item types

The two specific additions to the item types we produced were 'exhibitions' and 'performance', alongside 'art/design item' (Figure 7). This allowed us to identify 'exhibitions' and 'performances' as mediums of research dissemination. The whole process of tackling the metadata was to try and adapt them to the arts. This not only involved adding or removing certain metadata fields, but also adapting the language used for metadata fields as well as for the help text. For example, 'abstract' was changed to 'description' since 'abstract' referred specifically to text. Originally 'art/design item' was 'artefact' and this particular change was influenced not only by our own opinions but also by our interviews and usability studies; it was apparent that the majority of researchers not only did not use 'artefact' but were sometimes unsure as to what it actually referred, especially since they would only be depositing the digital representation itself and not the actual 'artefact' itself.

The key differences between the metadata schema for item types are obviously between those that are text-based and those that are not, i.e. art/design, show/exhibition and performance. Our schema reflected the many instances of collaborative work and where there had been contributors to that work. It was necessary to have fields where you could list the venues of a particular exhibition and if a specific piece of work had been part of other exhibitions, e.g. group exhibition, solo exhibition. We also included fields to allow description via the media of the object itself. For example, we may have digital photos of a piece of hand-built glazed earthenware:it is the earthenware that we want to describe in the 'material' field (Figure 8),

Figure 8: Material metadata field

but the digital photo format will also be detailed in the image description (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Image format

The further details section allows more information about the work or the researcher to be included. The field for 'additional URLs', provides us with the opportunity to link to the Web sites of the researcher or gallery. This helps to align the repository to researchers' desire to promote themselves and their own research.

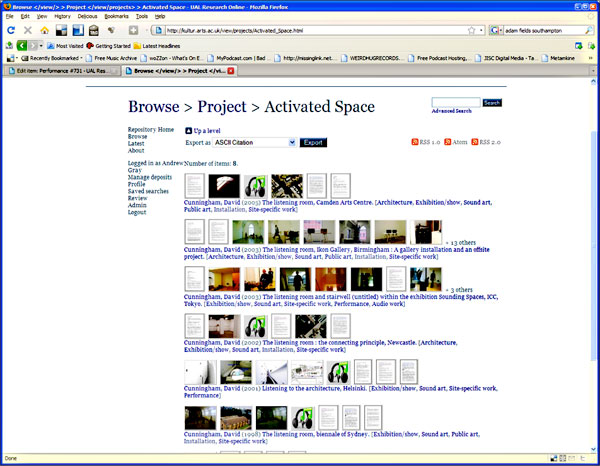

The linking of different records was a specific issue when dealing with researchers who produced different but related research outputs. One researcher produced and installed a different sound installation in a number of cities; each time the installation was different and had different documentation, but it was all part of the same project. To enable this linking we added a 'project' field to the metadata. This field was 'hotlinked' so that clicking on the project title would draw up all the related records within the repository (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Records by 'project'

While this is an effective way of showing what has been done within the project, it still relies on the depositor entering the information. This also presupposes previous knowledge of earlier work by the researcher on this project. If researchers are depositing it themselves this would not really be a problem, since they would have such fore-knowledge; when it is mediated deposit and if more than one person is depositing work over a period of time, such linking could break down. One possible solution would be to request such detailed information from researchers when they supply work to be deposited.

Support

What is clear from the project, and from the embedding of the institutional repositories within our institutions, is the need of specific and clear support together with guidelines for our researchers and people working with the repository. The gathering of material and eliciting of information about that material is of prime importance. To do this, we need to also allay fears, misconceptions and ignorance in respect of copyright and IPR. Because of the complexity surrounding copyright and IPR in the creative arts, VADS produced a series of guidelines and 'scenarios' for us to use as part of the promotion of our individual repositories. At UAL the repository has revealed a great demand for information about copyright and IPR from our staff in order to gather work for the repository and to protect and educate staff about their rights and relationships with other rights holders.

A Future

While institutional repositories have been around for a while it is still a young concept. Institutional repositories for the creative arts are even younger and there will be constant development needed to integrate such a system fully within arts research. There were a few areas of development that we had hoped to work upon in the project timescale but time worked against us. One area was the development of research profiles. This was an area that continually arose in our meetings with researchers and in the course of our interviews. Researchers used research profiles as a means of promotion; when passing us their work, they would often also attach their research profile as a means of highlighting their practice and to provide contextual background to their research. Another area that we were not really able to solve in any meaningful way was critical commentary on particular pieces of research. Reviews of exhibitions in magazines and blogs are important in judging the influence and impact of certain areas of research. Our problem was that we could only supply a link to a piece online with no guarantee that it would be there in a year's time. The issues of copyright loomed large over this. We found that staff would often scan newspapers or magazines that had commented, or conducted interviews, on their work and as such we could not put them into the repository. The actual way that art research is valued is often outside the traditional academic structure and these sites of critical exploration can often be transitory.

One need that became apparent, as we advocated the repository and sought material for our demonstrator, was a digitisation service. Many times I contacted research centres, introduced myself and the Kultur Project and asked if they would be documenting a conference or research project, only to be told that they would be very happy for me to come along and video/record their 'conference' 'project'. A lot of research activity is happening across the university but with no systematic digital documentation. If as an institution we were able to offer this in some form, we would be offering a definite service and would gain not only material for the repository but also 'friends' within the research community.

In a community that is as so diverse as the arts, with its varying disciplines, cultures and outputs, a real advantage was to bring the evidence of their research together. For many of the researchers to whom we spoke and demonstrated the repository, it was of great interest that the work we held was from a number of different institutions. The fact that you could see work from Winchester School of Art alongside work from Maidstone College of Art as well as Chelsea School of Art was a impressive. Therefore some surprise and notes of regret were expressed that, at the end of the project, the three institutions involved would be gaining separate repositories. Maybe there is scope for future development that would link up different arts repositories and increase the availability of arts research to all, and so encourage even more collaboration.

Conclusion

The Kultur Project tried to address a neglected area within institutional repositories. The arts community is as diverse as it is similar, yet there is a growing and pressing need to gather, sustain and promote the research within this valuable discipline. A repository is also a way to add value to such research by demonstrating that it is research. There are still significant developments to pursue, and there are art practices to convince that such a system as IRs can help provide an arena for dissemination. The success of the project will partly depend on the success of each institution's use of its IR and how its researchers engage with it.

References

- JISC Repositories and Preservation Programme

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/reppres.aspx - JISC Repositories and Preservation Programme Meeting

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/reppres/reppresprogconf.aspx - JISC Repositories Start-up and Enhancement projects

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/reppres/sue - Rumsey, Sally (2006). The purpose of institutional repositories in UK higher education : a repository manager's view. International journal of information management, 26 (3). pp. 181-186. ISSN 0268-4012

http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000800 - Stevan Harnad, Les Carr, Tim Brody, Charles Oppenheim, "Mandated online RAE CVs Linked to University Eprint Archives", April 2003, Ariadne, Issue 35

http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue35/harnad/ - Daisy Abbott, Sheila Anderson, Digital Repositories and Archives Inventory: Conclusions and Recommendations, April 2009

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/reppres/draireport_concl_final.pdf - Daisy Abbott, JISC Final Report – Digital Repositories and Archives Inventory Project, July 2008

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitalrepositories/drai-end-project-report.doc - Questionnaire: Putting Creative Arts Material Online: Your Views

http://kultur.eprints.org/docs/Questionnaire%20WEB%20VERSION.pdf - Victoria Sheppard, Kultur Project User Survey Report, August 2008

http://kultur.eprints.org/docs/Survey%20report%20final%20Aug%2008.pdf - Victoria Sheppard, Andrew Gray, Dominic Persad, Kultur Project User Analysis: Interviews Report, November 2008

http://kultur.eprints.org/docs/Interview%20analysis%20final%20Nov%2008.pdf - Dally, K. et al (2004) Assessing the exhibition and the exegesis in visual arts higher degrees: perspectives of examiners. Working Papers in Art and Design 3. ISSN 1466-4917. Retrieved 15 April 2009 from

http://www.herts.ac.uk/artdes/research/papers/wpades/vol3/kdfull.html - Marshall, T. & S. Newton (2000) Scholarly design as a paradigm for practice-based research. Working Papers in Art and Design 1, ISSN 1466-4917 Retrieved 31 July 2009 from

http://www.herts.ac.uk/artdes/research/papers/wpades/vol1/marshall2.html