Share. Collaborate. Innovate. Building an Organisational Approach to Web 2.0

The National Library of Wales has recently published a new Strategy for the Web [1] which integrates Web 2.0 with the existing Web portfolio and seeks to provide an approach to Web 2.0 which is focused on the organisation. Rather than centring on technical developments, this paper outlines a strategic research approach and discusses some of the outcomes which may speak to others seeking to engage with emerging Web technologies and approaches.

But Why...?

If Web 2.0 is a grass roots, organic and personality-focused shift in technology and approaches – as it is so often touted – is it not it counter-intuitive to think about an 'organisational approach' or to consider trying to write a strategy for development in this area?

Over the past five or so years Libraries, Archives, Museums and other organisations both within and outside the cultural sector have begun to experiment with a wide range of approaches aimed at engaging or interacting with their users via the Web. Moreover, in expertly designed courses staff at all levels are shown how to create blogs, re-use Flickr images, upload video to YouTube and create a corporate presence on FaceBook.

In the course of researching for the Library's new Web Strategy we came across many organisations which had firmly sought out opportunities to use social networking and other tools to meet their users 'on their own terms' and which had become disenchanted with the level of commitment required, and the lack of interest from those users. At the same time, lots of individuals and cultural heritage bodies have involved new and existing audiences in lively and interesting discussions about their future, or provided free public reuse of their resources in innovative ways.

Whilst what distinguished success from failure in these instances was often not a paper document outlining what was to be achieved but a combination of organisational support, a willingness to experiment (and to fail) – and most importantly – a clear understanding of what was achievable. To be successful, both organisations and individuals had genuinely to believe in the potential of any new service and to follow through on that belief with support for staff and technological developments. A strategic approach allows us to scope and outline such 'beliefs' in order best to begin to realise – on an organisational scale – the full potential of Web 2.0, beyond the personal level. Furthermore, this strategic approach engages directly with the most important aspect of what might loosely be defined as 'Web 2.0' – philosophical, cultural or attitude change, rather than mere technological novelty.

The advantage of an organisational approach is that rather than simply exercising the potential and passion of individuals, the potential for long-term and widespread engagement can be harnessed through a cohesive network of individuals with a shared strategic aim. Whatever we come to understand by the term 'Web 2.0', it is clear now that it is not a single instance of change, to which we must re-tool and respond, but rather a signifier of an ongoing change in user expectations and a strategic approach which provides a platform for organisations to reflect and change in order to meet this need in the future.

Defining the Problem

The National Library of Wales is not an organisation unused to the Web, we have provided a wide range of services via the Web for over 10 years with a consistently growing range of resources available online, and a strong growth in user numbers. The Library is also committed to an ambitious digitisation programme which will result in large parts of the collections being available online, at no charge, to users.

Like many organisations our current Web portfolio is the result of extended organic growth, providing new and exciting content or applications to users in response to particular project requirements. In the course of the last 10 years the Library has also undertaken a number of extensive redesign/restructuring tasks – the last being in 2007 when the Library moved from a mostly static HTML infrastructure to the open source Typo3 Content Management System [2].

We also have a variety of experimental projects involving Web 2.0 technologies, particularly in relation to building presences on external Web sites. These individual pilots have provided us with a great deal of useful experience, and they have also raised many interesting questions: Why did our number of 'fans' grow whilst the number of daily views stayed level? Why do users not talk on our 'official' page but they do on community-generated ones? How come the 'same people' seem to sign up to all of our external pages? Why do Wikipedians seem to worry more about the copyright restrictions on the images we share with them than their quality or content?

We had begun to see that Web 2.0 would be a change which affected all aspects of our business – that we would have to grow our own understanding of what 'Web 2.0' was in order to respond appropriately. In response, the Library convened a task group in 2007 to bring together our understanding of all aspects of Web 2.0 – technological and non-technological – in order to inform the Library's general strategic planning.

The resulting discussions greatly enhanced our understanding of the different interpretations of the term, and the potential for misunderstanding in seeking to change our approach. It also highlighted the need for us to develop further in this area – and quickly – in order to avoid a significant gulf between our Web presence and our users requirements emerging over the coming years. As a result, when the Library published its 2008-9 to 2010-11 strategy Shaping the Future a clear commitment to renewing our approach was made, stating that we will:

[Take] advantage of new online technology, including the construction of Web 2.0 services, to develop progressive ways of interacting with users. It is expected that the Library itself will provide only some specific services on its website. Instead, the intention is to promote and facilitate the use of the collections by external users, in accordance with specific guidelines. [3]

Researching the Strategy

With this commitment in place, the Library appointed a Senior Research Officer for six months to undertake the research, planning and writing of a new strategic document which would underpin our work in this area. As anyone who has tried to write such a document knows, there are two essential requirements for creating any effective, and achievable, strategy: knowing where you are and knowing where you want to be. Without a clear and collectively recognised view of these requirements, no organisation can ever hope to do more than wander in the interesting but ineffective wilderness of experimentation. With this in mind, our strategic research began by taking the time to look internally at our current activity and to discern our potential for development before looking at examples of success and from other similar and markedly different organisations in the public, private and third sectors.

This approach defined the nature of our eventual strategy. Rather than following the route of detailing our existing infrastructure we were able to confidently outline the strategic objectives which would move us from our current approach to one in which we could continue to meet user expectations into the medium and long term.

Ready for Web 2.0?

It might seem self-indulgent, and even restrictive, to begin the process through introversion. However, by asking the question 'Are we ready for Web 2.0?' we were able to both answer the concerns of those who felt that our organisational culture would not support attempts to engage effectively in these new ways and to look outwards with a realistic view of what might be achieved within the three-year life of the strategy.

This portion of the research fell into four key areas: a re-analysis of the statistical data we were already collecting; a skills analysis of staff involved in working with the Web at the Library; a review of what content sources we already had, and how they were used; and more open discussions and surveys with staff across the organisation. In the sections below I give examples of the kind of insights which arose from this portion of the research.

Statistics

It would be rare to find an organisation which does not keep and monitor its Web statistics; providing headline figures to relevant committees, funders and other interested bodies. However, rather than looking at the constant positive growth within our access data, we sought instead to look for significant patterns which might indicate either problems or potential within the content currently available to users.

One of the first issues which arose through this was that much of the detailed information simply was not there, or could not be relied upon to provide consistent – deep – data about user activity. Although we were using the same reporting software for all of our locally run sites, it was not easy to track users across 'microsites,' and harder still to see if any of the external presences we operated were effectively linked to our centrally managed content. At the same time, it was difficult to separate headline usage figures from the areas of Web content we were seeking to push at any time – we 'knew' that a link from the BBC News Web site to one of our digitised manuscripts brought many more visitors, and could relatively easily tell that they visited that specific content, but knowing whether they explored the rest of our Web offering, or 'bounced' (left almost immediately), took hours of painstaking analysis.

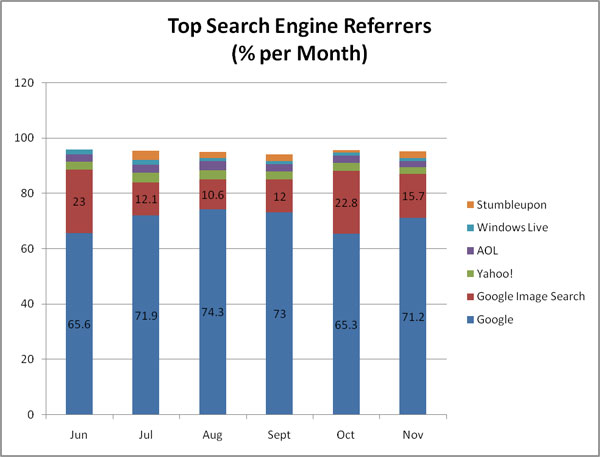

However, we were able to find some interesting trends in our data – ones which drove home the impact which Web 2.0 approaches and technologies were having on the way our site was found, accessed and navigated. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of users of our Web site came to us direct from search engines. However, whilst Google made up around 85% of our search engine referrals the remaining visitors were split across other well-known search engines and the social bookmarking site 'StumbleUpon' (See Figure 1) – which on the basis of only a few user-added links provided the same level of visits as Yahoo! or Windows Live Search.

Figure 1: Search Engine Data for June - November 2008

It was clear from the data that what users were doing in relation to our site was as important as any search engine optimisation we might have undertaken in-house. Gone are the days of encouraging users to bookmark our sites in their browsers, now a digg mention, tweet or delicious entry brings in the visitors.

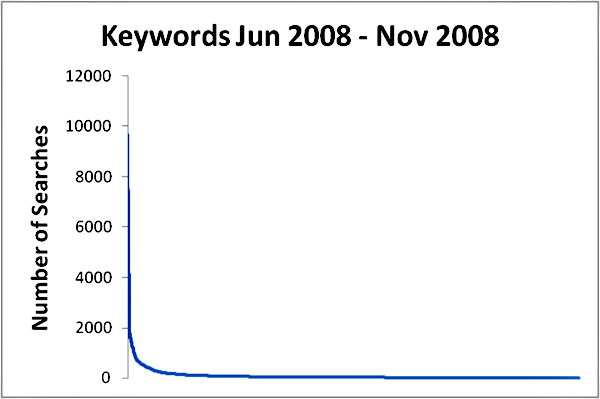

With search engines being such a key element of our visitor sourcing we also sought to understand more about what those users were seeking from our site. Unsurprisingly we found that key relevant terms (library, archive, family history, and so on) made up around 18% of our search engine visitors. However, the remaining 82% came from a long tail [4] of place and personal names and other weird and wonderful search terms. The overwhelming majority of our users were viewing our site for reasons we had never anticipated – and these users represent an audience which can be attracted to visit the catalogue, digital exhibitions or online shop.

Figure 2: The 'Long Tail' of Referring Keywords

One point which became clear was that high-level visit and hits numbers are not really useful in managing and developing Web content. Positive growth of these figures will probably indicate that a Web site is expanding, but cannot tell you whether those visitors get 'value' from the content, and cannot tell you where you should position new content types to give the best user experience or whether your users take the time to visit more of the site than the page which the search engine suggested to them.

Finding real and important trends within statistical data is not an easy task, however tools such as Google Analytics [5] provide much more interpretation than traditional Web statistics software and can be helpful for anyone looking to see the impact of their Web portfolio.

Skills

Perhaps one of the most difficult elements of the research was understanding which skills were already present within staff both working with the Web and in other, less directly related, positions. Only by reviewing both formal training and informal self-development were we able to understand the breadth of skills within staff, and the potential gaps which might require further development. We were able divide our skills into three key areas: technical, content management and content producers. In simple terms the technical skills allowed us to 'build' services, the content producers gave us the raw material to populate and run the services, and the staff with content management skills allowed us to shape, manage and grow them.

What was clear was that our technical staff were well equipped to develop rich and innovative Web applications. However, this in itself required an increased focus on content production and management. To avoid being purely technically led would require us to develop and maintain the 'softer' skills of content scoping and development. However, within the organisation we already have a growing community of bloggers, twitterers and social networkers – alongside experienced writers. Key to our future development of content creation would be the channelling of these skills into improving our online services to users.

Finally, in order to sustain this focus – and indeed to develop the potential into the future – we would need to improve the skills of staff across the organisation. However, our experiences with the Library's own Content Management System had shown that merely running training sessions would not deliver real skills development. Instead a more innovative approach, such as the 23 things model [6], is required to support the personal digital development of staff – enabling them to see these skills as useful within their own work.

Sources

What arose from both evaluating our current Web offering, and discussions with staff responsible for managing and providing access to the collections, was that we had a huge potential for offering more, and more effective, content and services via the Web. Whilst we had a mature and diverse range of digital content available through both the Library's catalogue and Web-based digital exhibitions, there was a significant proportion of material which was not being exposed to the extent that it might be. We were able to define four distinct 'source types' which would make up our Web content into the future:

- Information: Resources which describe the Library and its provision of services (Opening Hours, News and Events, Promotional Images or Video), professional information (including staff presentations and papers) and the products of events held at the Library (such as videos of invited speakers).

- Interpretation: Resources which make use of staff knowledge and experience to provide added value to users of the collections (Family History Information, Enquiry Responses, Research Support).

- Metadata: Data which is explicitly about the collections, most commonly held in the Library Catalogue but also as additional finding aids.

- Digital Content: Products of the Library's digitisation programmes or, in the future, content collected in digital form, including full text automatically extracted from scans.

It is these sources that fuel, and will continue to fuel, our Web portfolio into the future and we were quickly able to see how the information which was currently available online did not necessarily reflect the true extent of useful information at our disposal.

Culture

Initially the research had hoped to simply appraise staff experiences of the current Web operations, and to try and explore whether our current infrastructure and approach was delivering on the potential that each part of the organisation had recognised. However, throughout a series of group discussions with key teams of content gatekeepers and front-line service providers, a wider theme of 'cultural capacity' began to be identified.

Staff at all levels were actively interested in engaging with new ways of providing user services and with sharing the Library's collections, metadata, professional activity and events through new ways of working. However, they felt disenabled and unconfident in undertaking this work themselves, without formalised approval from groups or committees. This 'cultural' element has become an integral thread in how the Library's approach is defined, and will be central in future implementation tasks and actively reinforcing organisational support for this work, at all levels, and is a significant benefit from the strategy itself.

Future Directions

The second half of the research involved working alongside organisations from around the world to explore how different technologies and approaches had been successful in engaging new and existing users. Rather than spelling out in detail the various positive and negative outcomes of different approaches and technologies, in this section I will draw together some of the more interesting themes which supported successful Web 2.0 services.

Community Understanding

By far the most important success factor for any Web service, most especially those which focus on interaction, is an understanding of the community which it serves. This, of course, is also true of physical services however it is common for people to consider Web 2.0 functionality as 'added value' without fully understanding how it might be used. User-created metadata, for example, is often held up as a triumph for both the 'crowd' and the content owners; but the reality of such projects is that unless a community of taggers can be built around the service, the result is little more than a few disparate, generalised, tags.

Although some projects had been surprised by the communities which used their services (expecting, for example, family history researchers, but instead getting young people looking for homework help), those who respond and engage with these new communities are rewarded with interaction. Projects which do not re-evaluate their expectations of the community feel, instead, disappointed by engagement of 'the wrong type' of users.

Agility

One of the reasons that Web 2.0 is looked to as a potential benefit to organisations is the way in which innovative services can be delivered quickly and cheaply. In fact, with most Web 2.0 applications a large number of staff, significant budget or extended timescale can be a considerable disadvantage. Instead, effective Web 2.0 services normally rely on a small committed group to deliver an initial product quickly, often a beta, and then to continue to develop new services or to engage actively with the community of users.

This agility comes from a level of personal commitment from the staff involved. Because of the lack of long-term experience with many Web 2.0 approaches, it is difficult to see how this agility can be retained in the longer term, given staff turnover and loss of interest (see Sustainability and Risk below).

Appropriate Content in Appropriate Environments

Anyone who has responsibility, knowledge or often just an interest in Web 2.0 will tend to be regularly asked questions along the lines of 'Shouldn't we have a presence on Twitter/FaceBook/MySpace?' However the most effective Web presences, and particularly those that use Web 2.0 elements, are notable by their focus on one particular category of type of service.

Selecting the right type of content for the right kind of environment is essential to success. It is important to understand that whilst organisations might wish to share detailed information on their activity, FaceBook or Twitter may not be the right place to do so. Organisations often feel that we must 'go to where the users are' but to do this successfully we must understand what they are doing there. Adding an organisational presence on a space which users regard as 'social' or 'relaxation- focused' may be seen as invasive or inappropriate.

Similarly, organisations need to be prepared to tailor or select content in a way which fits the environment. The hardest question for those evaluating whether they should invest resources in a Twitter stream, blog or social networking profile is whether they add value to the users' experience. Too much or too little relevant content can cause more damage than simply accepting that your voice is best heard elsewhere.

It is not possible simply to recycle existing content in multiple environments without making it clear to users that you see one or many of the outlets as merely a passive broadcast. Finally, any organisation or project must accept that, without enough relevant things to say, any form of social networking or interaction will be unsuccessful. In short, each of us must ask the question for every social content stream – are you really as interesting as you think you are?

Sustainability and Risk

One of the most common concerns expressed about using Web 2.0 services, particularly in relation to those provided for free by Web companies such as Google, is the long- – or even medium-term - sustainability of the service. It is true that organisations and individuals invest significant amounts of time in such services with little or no guarantee that they will continue to be supported, or even available, in the future [7]. The same is also true of services (such as blogging) which can become personality-centred – staff move on, become uninterested or refocused, and this can severely undermine such services.

The simple answer to this problem is that Web 2.0 is not an environment which can be 'moved to' but is, rather, the next step on the service provision journey. At some point all of these services will change, become ineffective, or unused, regardless of the sustainability of the project. This is not a risk that can be mitigated but instead represents a fundamental understanding that the Web is temporary by its nature, and that all content should have a clear lifespan. Truly persistent services can only reliably be provided through locally run or managed sites, but this does not undermine the potential of external services and points of presence.

Even if FaceBook could guarantee its survival for the next 20 years it is unlikely that those of us running profiles will want to communicate through the service in 2029 – the community we are seeking to engage with will have moved on far before then. Effective planning involves balancing the resources spent on a service (Web 2.0 or otherwise) with the likely lifespan and moving on to more appropriate environments when required – not maintaining a portfolio of unmaintained and underused 'digital curios'.

Services and Content Spaces

It was clear from the research that the nature of service and content delivery on the Web is still undergoing a fundamental shift. Web 2.0 had provided 'new places' and 'new ways' for us to reach users but it was also a symptom a wider change in the way in which we will understand and experience these services into the future. The traditional view of the Web was that each new service required its own content space, so the development of a new element of user provision would require its own attractive URL, brand and interface. More recently this approach has broken down and, whilst services which are regarded as 'important' are often still treated as separate entities, many additional features are merely added to existing content spaces – improving the experience of existing users by upgrading the existing service provision.

The most innovative services are now developed in the clear knowledge that they do not require their own content space, that there may never be a 'primary' point of access, but instead that the service might be accessed from other Web sites, Virtual Learning Environments, social networking sites, iGoogle or from a mobile phone application. Rather than focusing on the superficiality of an attractive interface – and creating yet another content space – these services leverage the potential of other content spaces to provide the framework for their interface, and the ready crop of users.

The drive to produce a standalone Web site is still very strong, particularly outside the rapidly developing digital media industry. What is obvious, however, is that users are spending more time in 'their' spaces and less in 'ours' and that time and resources spent on delivering a 'content silo' are wasted from the point of view of a user who 'dips in' to sites from other destination Web sites, or from search engines.

An Organisational Approach

The final strategy itself takes the Library's existing resources, skills and, most importantly, potential, and outlines how this might be applied as a foundation for short- and longer-term development. Rather than creating a separate strategy for 'Web 2.0' activity, and running the risk of disassociating the significant resources already deployed, the final document refers to all of our Web activity – regardless of environment.

This will, through the life of the strategy, provide the underlying support for current and future activity in all online spaces as well as acting as the catalyst for innovation in new areas which we cannot as yet identify. The strategy itself details five strategic objectives which are broken down into 24 individual goals; however below I will discuss three groups of activities which could be considered 'transferable' by other organisations seeking to make the most of Web 2.0 opportunities.

Consolidation and Configuration

Rather than seeing Web 2.0 as a 'bolt-on' technology which will enhance existing user experience, we have identified the need to look in depth at both our content and technology in order to move towards a fully integrated Web 2.0 platform. In its simplest terms this involves identifying key platform-pages and content areas for delivering interactive services – allowing us to roll out different approaches across our existing content or to reconfigure that content better to fit the needs of our users.

Defining a content structure based on general user types (physical visitors, external users and fellow professionals) allows us to focus the content so as to ensure that users can navigate across relevant and attractive services. This will increase the number of pages visited by each user and treat each search engine referral as an opportunity to 'convert' users, to encourage them to look around the site.

At the same time, a clearly defined technical infrastructure – built around core components – will help to make better use of our development resources as well as building skills around a focused framework. Using technologies, design and layout to ensure that our various different platforms (including the catalogue) feel comfortable to users is also an essential part of this work.

Moving from an environment where each project, output and group can be directly involved in defining its own distinct Web identity (specifically tailored to their own view of the future users of their content) to a single 'family' of brands is a difficult decision for any organisation. It takes a strong 'brand manager' to sell the benefits of an umbrella organisational approach over bespoke environments, balancing the requirements of funding bodies with the needs of users, and we have yet to see how this approach might be fully realised over the next three years at the National Library of Wales.

Collaboration and Sharing

Part of our move towards a more forward-facing Web environment has involved accepting that in many cases we may have a role providing resources but not necessarily services based on them. As an organisation, indeed as a sector, we have traditionally been open to sharing; however, the modern user is increasingly requiring (or assuming) the right to reuse our content on a personal level. The first step towards this approach will be determining which Library-produced content (such as interpretive text) can be made freely reusable under a Creative Commons [8] licence. However we will be going beyond this by reviewing the potential (where possible) of relaxing the rights over our digital content and metadata – so encouraging the open and free reuse of this content by end-users.

These important changes will begin to shift our relationship with external users fundamentally, and we will build on such changes by adding more content – particularly in the form of events, alternative content outlets (such as blogs), professional documents and presentations – to our Web offering. Looking further ahead we will also be looking for partnerships in order to exploit the semantic markup of our data and to explore ways of exposing our content in increasingly machine-readable ways.

Measuring Our Success

Fundamental to supporting our continuing development, outside and beyond the life of this strategy, will be our re-evaluation of how we determine a 'sucsessful' Web presence. Rather than just counting visits and hits, we will be looking at key trends for content, evaluating 'micro-feedback' in the form of page ratings, reducing the bounce rates of our key entry pages, and counting the number of Active Interactions. We define Active Interactions as being activities above and beyond simple viewing – such as a user making the effort to 'friend' the Library on a social networking site, playing an online game, tagging content or leaving a comment.

These elements themselves will allow us to judge the success of all of our Web 2.0 activities and reduce the risk of developing underused or undervalued services.

Conclusion

As we step forward into a three-year implementation phase, we can begin to see the value of this organisational approach. Staff from across the Library are now becoming more involved in the design, delivery and construction of our online Web presence. We have also taken some significant decisions in terms of how we will resource and support this work within the organisation – combining distributed roles into a single Digital Media Unit, tasked with supporting the wide variety of work required across the organisation.

However we will only really begin to judge the benefits when we can see developments for new ways of delivering content and services coming from within the wider organisation. By spending time and resources undertaking a significant research and planning exercise, we have been afforded the opportunity to place ourselves as a sharing, collaborative innovator in the eyes of our colleagues, funders and – most importantly – our users. For the Library, the next challenge is to realise this opportunity.

References

- Share. Collaborate. Innovate. A Strategy for the Web 2009-11

http://www.llgc.org.uk/fileadmin/documents/pdf/2009_Web_Strategy.pdf - Typo3 CMS http://typo3.com/

- Shaping the Future: The Library's Strategy 2008-9 to 2010-11

http://www.llgc.org.uk/fileadmin/documents/pdf/nlw_strategy_s.pdf - Anderson, C. (2005) The Long Tail: How Endless Choice is Creating Unlimited Demand

- Google Analytics http://www.google.com/analytics/

- 23 Things Model http://stephenslighthouse.sirsidynix.com/archives/2008/02/the_23_things_l.html

- Kelly, B., Bevan, P., Akerman, R., Alcock, J., Fraser, J., 2009. Library 2.0: Balancing the Risks and Benefits to Maximise the Dividends.

Program Electronic Library and Information Systems, 2009, 43 (3), pp. 311-327 (and also a range of other excellent work in this area by Brian Kelly) - Creative Commons http://creativecommons.org/