From Passive to Active Preservation of Electronic Records

Heather Briston and Karen Estlund provide a narrative of the process adopted by the University of Oregon in order to integrate electronic records management into its staff's workflow.

Permanent records of the University of Oregon (UO) are archived by the Special Collections and University Archives located within the University Libraries. In the digital environment, a new model is being created to ingest, curate and preserve electronic records. This article discusses two case studies working with the Office of the President to preserve electronic records. The first scenario describes working with the outgoing president, receiving records in a manner very similar to print records, where the Archives acted as a recipient once the records were ready to be transferred. The second scenario describes actively working with the new president’s office as records are being created with the move to the Archives’ permanent records part of the planning. In both cases, relationship building was essential to success.

Organisation Background

The University of Oregon is a public university. As a public agency the University’s records are public records and their retention is scheduled by Oregon Administrative Rule [1]. The rules prescribe both the maximum and minimum retention period for the records created by the University. In the case of the records created by the Office of the President and the president himself, the vast majority of those records are required to be retained permanently and made accessible in due course by the University.

Although the University Archives had previously received some electronic records, the departure of the University President in 2009 marked the first large-scale transfer of electronic records to the University Archives. The Office of the President records, documenting the history of the institution, also represents one of the most important collections for an archives to receive.

Receiving the Records of the Outgoing President

In summer 2009, the UO President retired after fifteen years in office. During his presidency he was the first president to use email for communication extensively and create electronic records including Microsoft Office files, photographs, video files, and Web pages. At the same time he also sent and received correspondence on paper, and his office had a policy of printing and filing documents in a triplicate filing system based chronologically, alphabetically, and by topic. It is generally assumed that record collections are and will remain hybrid print and electronic collections for the foreseeable future. The outgoing president’s office turned everything into print; whereas, the next president’s office would adopt a policy to turn everything into electronic copies.

There was an established routine for transfer for paper records between the Office of the President and the University Archives; however, electronic records required a separate workflow that raised many new issues for the Office. No electronic records were transferred to the archives until the President had officially retired and they were organized by his former Executive Secretary. Within the Office of the President and across campus, it has taken time to understand that electronic communication is covered by records laws just as much as paper communication. Email was a particularly difficult problem as it is often -mistakenly- regarded as unofficial, with only selected important documents being printed for preservation.

There also arose a concern for security of the electronic records due to the sensitive nature of the materials. Although records may be public, many of the documents are subject to federal and state confidentiality laws, as well as exemptions from the state’s public records law [2]. Many records creators at the University are concerned about the ease of inadvertent disclosure of electronic records, especially when disclosed out of context. (In an earlier project, an outdated organisation chart was found in our institutional repository [3] through Google. As a floating PDF file, there was no way to let a user know it was outdated and the archives received complaints from University administration.) Building upon the relationship that had developed over the years between the President’s Executive Assistant and the University Archives, assurances were made that measures were within place in the preservation infrastructure that would avoid unauthorized access and limit inadvertent disclosure.

With these understandings in place, representatives of the University Libraries worked with the Executive Assistant to the President to prepare the records for transfer. The Executive Assistant went through the documents and email collections and filed many messages, discarded junk mail, and flagged confidential messages prior to transfer. In a collaborative meeting with campus IT and the President’s Office we ensured that everyone was comfortable with the transfer and arranged to have all of the electronic records transferred to the Library’s possession via a DVD.

Setting up a Flexible Infrastructure

When deciding how to handle records received, it became clear the Libraries would not be able to implement a new content management system due to lack of the necessary additional funds and extra systems support, a position aggravated by the lack of viable systems on the market. What we were seeking was a system:

- flexible enough to migrate easily to an e-records system if later implemented

- able to scale to handle more offices on campus

- able to accommodate appropriate security measures, and

- linked with the paper records.

Planning for Preservation

In order to plan for preserving these records, The Libraries employed the PLATTER checklist developed to aid implementation of a preservation plan [4]. This tool was used to help guide decisions for ingest, migration schedules, institutional support, technical infrastructure, staffing and responsibilities, and access conditions. The PLATTER checklist was selected over more recent tools like the Trustworthy repositories audit & certification (TRAC): criteria and checklist [5], because it had immediate applicability and did not bear as large an administrative barrier to its completion. The OAIS model [6] was also consulted to identify areas of workflow and storage with our makeshift system.

Ingest

In order to mirror the process for paper records, the Libraries wanted record creators to be able to ‘deposit’ their records with the Archives. In the case of the retired president, they handed over a DVD, but this was never intended to become a regular transfer method. As was learned from the ingestion of materials into the Libraries’ Institutional Repository, self-submission Web forms can be a barrier to participation when working with many faculty and departments. In order to utilize procedures already familiar to Office of the President staff, a network shared drive was created, to which the staff could map deposit records on a regular basis. In this model, each department has its own folder on the Libraries’ network with permissions restricted to only those in that department and representatives of the University Archives. No new skills needed to be learned and each deposit is made with an inventory list similar to what is required for physical box deposits intended for the Archives.

The initial batch of records from the outgoing president’s office consisted of over 6,000 electronic files and additional embedded files in 24 formats. (The subsequent collection, consisting of 3 months of the new president’s records, encompasses approximately 2,000 files.) Once in University Archives, digital preservation strategies put in place by the Libraries were initiated and access provided through tools currently used by Libraries and Archives staff. During the initial evaluation of the files, file names were changed to standard forms without special characters or spaces and proper file extensions were applied for those missing them. The files were inventoried using DROID (Digital Record Object Identification) [7]. A text file was exported from DROID with the file list and saved alongside the native and converted files to be kept in a central location, where it acts as a store for all file format lists and is maintained for assessing any necessary future file migrations. The majority of office documents in the first batch were also converted to PDF files with a footer attached identifying the document as an access copy; however, this is an experimental procedure and the documents may be returned to read-only MS Office formats.

Email once again presented a special case. Since .pst file format has recently been released as an openly published standard [8], the Libraries opted to retain the email in its original format for preservation purposes. The rationale for this decision is that the Outlook format provides a much easier way to read and view files, especially with the extensive mark-up and categorization within the .pst file. With the published standard, the format can be converted to a myriad of text files or XML files in the future if necessary, but at this point another version is largely unusable.

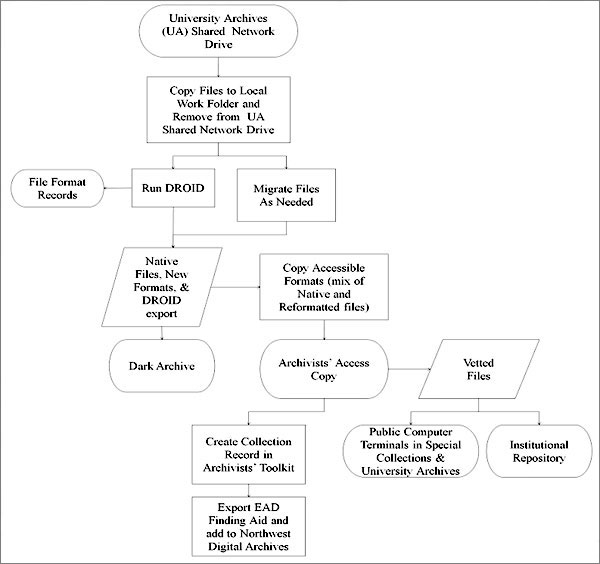

Archival Storage, Data Management and Access

Evaluation of the Libraries’ current content management systems, DSpace [9] and CONTENTdm [10], found that both systems were not ideal, as they were designed for item level cataloging, and there was concern that the burden of getting information into them was not worthwhile for closed records. The University Archives also uses the data management system Archivists’ Toolkit [11] to enter acquisition records, and all paper collections had records in that system. In order to accommodate all immediate needs and remain flexible, the traditional file system was used with additional workflow steps, and description residing in Archivists’ Toolkit along with the description of the paper records. There exist three distinct sections with varying access levels, content, and procedures for the collections:

- The preservation layer consists of the files in their native format and structure delivered by the President’s office along with migrated versions of the files. Records that were created in Archivists’ Toolkit to describe the files are exported into EAD XML and live on the server with the archival files. The files are backed up in multiple locations and check-sums are run to avoid bit rot. The log of the file types created during the inventorying process is kept to help monitor future migration needs if they arise. Because issues of confidentiality, privacy, and state and federal record laws apply, access to this section is restricted.

- The archivists’ layer consists of the preservation format of the files and is organized and tagged according to the system devised by the University Historian and Archivist. Records in Archivists’ Toolkit are used to describe the content and point to the server location of these files along with the paper records. This area is also subject to additional organization by the Archivist for ease of use.

- The public access layer is a redacted copy of the archives of files that have been determined not to breach confidentiality or contradict any laws guiding access. These files are available on a file server that allows for designated public terminals and staff computers to access read-only versions of the files. Future plans include providing access to files online, as risk is assessed, alongside existing online collections of University Records [12].

Figure 1: Preservation System

Actively Working with Current Office

The arrival of President Richard Lariviere in July 2009 signalled a new era for records creation and management not only in the Office of the President, but across campus. The new president brought with him an emphasis on information stewardship as a means of efficiency and cost-effectiveness. (Prior to his arrival at UO, Richard Lariviere was the Provost at the University of Kansas (Lawrence). While Provost he oversaw the start of a campus-wide, comprehensive information management programme, which brought together digital information security, electronic records management and archives, as well as digital asset management and preservation [13]. Most notably this meant an immediate shift to a ‘paperless’ office in the Office of the President where even print documents were scanned and made available in electronic form. With a change in many of the President’s staff, there also came a wider use of technology in both records creation and management.

The change in presidencies provided the Libraries with an exciting opportunity to move forward with latent programs for ingest, preservation, and access to permanent electronic records. The first step was to build relationships with the new staff in the Office of the President, especially those directly responsible for the records management in the office. They were very focused on managing their electronic records, and understood the importance of the records the office creates. To that end they have hired a person who has as one of their express duties the management and preparation of the records for transfer to the University Archives.

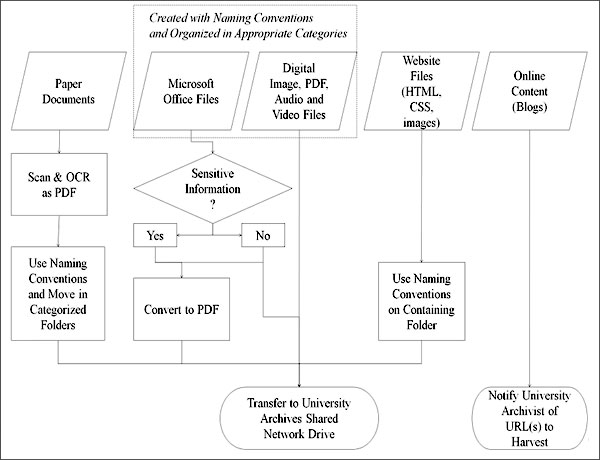

The Digital Collections Coordinator and the University Archivist have also worked with the Office to develop a workflow and provide training for managing electronic records. The three main areas for training are file migration, file naming conventions, and tagging files for retrieval.

Figure 2: Workflow of records to archives

As part of a transition to a paperless office, the current Office of the President necessarily used some processes from the previous presidency. For example electronic documents were printed out and rescanned to PDF for storage on networked file shares. By using tools already at their disposal and creating brief instructions, the Libraries were able to train the staff to create full text-searchable PDF files from Word and other documents using Adobe Acrobat Pro. Because the Office is not paperless, training was also given on Adobe Acrobat Pro’s native Optical Character Recognition (OCR) engine for documents that were scanned, so that they may be full text-searchable, as well.

The environment of the Office of the President demands that staff be able to quickly retrieve items as needed and the staff already understood the general principles of uniqueness and easily recognisable file names. Existing file names, however, had many special characters and spaces which the staff easily understood may cause problems. The Libraries showed the staff how to use a simple Freeware tool, ReNamer [14], to mass apply file naming changes and strip out unwanted characters.

The most exciting part of electronic records for the Office staff was the ability to tag and categorise files without having to make triplicate print copies. This was especially useful in the area of email, where the use of the tags and flags in Microsoft Outlook could help easily retrieve relevant emails. The staff has begun to make lists of desired categories with consultation help from the University Archivist and Digital Collections Coordinator, with the goal of creating a standard list of category names. Examples of these categories include: Correspondence, Reports, Speeches, Athletics, College of Arts and Sciences, etc.

Future of Electronic Records and the Archives

The effect of the arrival of the new President and his emphasis on electronic records has not taken long to spread across campus. Increasingly offices and departments understand that they can and must begin to responsibly manage the electronic records that they create. They now look to harnessing technology to create more efficiency in their work, and using it as a tool to their advantage. Some examples of this are the Office of Development that is migrating its donors’ visits and tracking documents to electronic form and managing it in a document library that development officers can access in their office all over campus, or on the road. The University Senate, in order to encourage wider participation and interest in campus governance, is filming their meetings so that they can be streamed online. As the minutes and other documents capturing the activities and decisions of the senate are considered permanent records, the recorded senate meetings will be retained and preserved by the University Archives. There is increasing use of Web 2.0 tools for collaborative student learning on campus; most of it is ad hoc, driven by faculty staff and the demands of pedagogy, or in some rare cases, student influence. One result is the creation of blogs for e-portfolios, particularly in business and architecture classes, and the potential for campus wide multi-user blogs for students and faculty. These campus departments are seeking advice from the Libraries on how to preserve these records.

Conclusion

By transitioning from a passive receivership role for University Archives to actively working with offices before records are created, we are able to have a more streamlined and efficient process for ingesting electronic records into the Archives. With the flexible infrastructure in place, we can easily adapt to the needs of more departments on campus and eventually implement a large-scale content management system if selected. The key to success in these cases is the relationships developed with the departmental staff and building upon familiar and efficient practices that also aid their daily work in addition to preparing the records for the Archives.

References

- Oregon Administrative Rule, Secretary of State, Archives Division, Oregon University System Records

http://arcweb.sos.state.or.us/rules/OARS_100/OAR_166/166_475.html - Oregon Revised Statutes, Chapter 192, Records, Public Reports and Meetings (Public Records Law),

http://www.leg.state.or.us/ors/192.html - Scholars’ Bank Home http://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/

- DigitalPreservationEurope, (April 2008), “DPE Repository Planning Checklist and Guidance DPED3.2”

http://www.digitalpreservationeurope.eu/publications/reports/Repository_Planning_Checklist_and_Guidance.pdf - RLG-NARA Digital Repository Certification Task Force. (2007.) Trustworthy repositories audit & certification: Criteria and checklist

http://www.crl.edu/sites/default/files/attachments/pages/trac_0.pdf - Reference Model for an Open Archival Information System (OAIS) CCSDS 650.0-B-1 Blue Book (January 2002)

http://public.ccsds.org/publications/archive/650x0b1.pdf - DROID from the National Archives of the United Kingdom, PRONOM http://sourceforge.net/projects/droid/

- Microsoft Corporation. (2010). “[MS-PST]: Outlook Personal Folders (.pst) File Format.”

http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ff385210.aspx - DSpace: http://www.dspace.org/ ; University of Oregon’s installation:http://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/

- CONTENTdm: http://www.contentdm.org/ ; University of Oregon’s installation: http://oregondigital.org/

- Archivists’ Toolkit http://www.archiviststoolkit.org/

- Electronic Records of the University of Oregon: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/151;

Office of the President records selected by UO Honors College students: http://oregondigital.org/digcol/uopres/ - Information Management: University of Kansas (KU): Office of the Provost & Executive Vice Chancellor

http://www.provost.ku.edu/infomanagement/index.shtml - [den4b] Denis Kozlov http://www.den4b.com/downloads.php?project=ReNamer