Characterising and Preserving Digital Repositories: File Format Profiles

Preservation: The Effect of Going Digital

Preservation of scholarly content seemed more straightforward when it was only available in printed form. Production, dissemination and archiving of print are performed by distinctly separate, specialist organisations, from publishers to national libraries and archives. Preservation of publications established as having cultural significance - printed literature, books and, in the academic world, journals fall into this category - is self-selecting and systematic in a way that has not yet been fully established for digital content.Digital content brings other advantages: new voices and a proliferation of channels and, for scholarly research papers, open access, for example. Research typically builds on earlier work: it is not simply about reading papers on that work but about acting on results and data and making new connections. Efficient, modern research, especially in science, needs to access to all parts of the published corpus, quickly and without barriers [1].

We have an excellent way of providing open access, through institutional repositories (IRs) on the Web. Where content is freely accessible in repositories and journals it has been shown to be more visible, is downloaded more and cited more [2]. This enhanced impact is made possible by digital content, the Web and open access, so we can see that IRs have a critical role to play. While it is good to be able to access content easily, we may want to return and use it again, as will others for highly cited work. That is why, when we have a significant body of good content that is well used in a repository, we find ourselves concerned with preservation: preserving access. However much we might wish to retain a semblance of the system of print preservation for digital content, we can see already how the landscape has altered: expanded range of content, new forms of presentation, improved access and changing audiences, all leave us seeking to recalibrate cultural values against which to select digital content for preservation. This is why digital preservation should be rooted in access and usage.

We know this view of what IRs do must be broadly accepted because it is embedded in Wikipedia:

‘An Institutional Repository is an online locus for collecting, preserving, and disseminating – in digital form – the intellectual output of an institution, particularly a research institution.’

Notice how this unwittingly combines responsibilities that are separate for print publications. No self-respecting IR appears to be willing to deny these functions, despite the fact that most repository software in use has been designed primarily to support collection and dissemination and less so preservation [3], although that is changing through the embedding of preservation tools in repository interfaces, as we shall discover. Yet, in terms of preservation, any IR that brings institutional support and an organised management framework to the purpose of collecting and disseminating content is already ahead of most Web sites that perform these same functions, and in many cases a long way ahead. As we have alluded to with regard to repository software, it is not a complete preservation solution, however, for which the growing IR will need to develop policy and engage in some active planning and decision-making.

There’s another important difference between digital and print, from a preservation perspective: when it comes to digital content, there is a lot more of it. At a personal level, just compare how many digital photographs you produce compared with those from film cameras. For some repositories it might not seem so, but institutions produce a wide range of digital content in large volumes - from research papers to data and teaching materials, across science and the arts and humanities - and repositories that have recognised this are growing fast. When content grows as fast as we find with digital, the old means of curation and archiving break down. New rules, procedures and tools have been developed and applied for digital curation, and now we want to widen usage to non-specialists, including repository administrators.

While a common understanding of digital preservation is to ensure continuing access at some point in the future to the content we can access and use today, what is less obvious is that digital preservation is also about ensuring the same for content a repository might receive tomorrow or at some later date. In other words, it involves planning for content we do not yet have. Far from preservation being just a task for the end-of-life of a digital object, it thus spans the whole content lifecycle. The lens of digital preservation can provide the vision for shaping the repository context.

This anticipation of future content is important if we are to approach the management of digital content as systematically as with print. Another characteristic of digital content is that formats change and, driven by new applications and requirements, new formats keep emerging - from HTML of the original Web, for example, to Web 2.0 blogs, wikis and other forms of social content, not to mention that by definition digital is a computed environment where content can be transformed and interconnected for presentation. There may be hundreds of popular digital authoring applications at any given time, and thousands of formats. The repository has to produce its preservation plan against this background of ongoing change, because a plan that fails to anticipate change is not a good preservation plan.

Institutions: Growth of New Types of Repository

We have already indicated how the role of IRs has begun to evolve to encompass new and wider forms of digital content. More specifically, we now have open access repositories, data repositories, teaching and learning repositories, and arts repositories, each institutional in scope, at least prospectively in some cases. Now imagine that such repositories were to coalesce into a single, coordinated institutional repository. Caution might dictate decisions on the scope of IRs, but it would be an omission and a failure if an IR were not to include a major type of output from the institution simply by being unaware of it rather than assessing the full implications and making a conscious decision to include or exclude such content.

We do not have such broad repositories today, but could this be the IR of the future, representing all outputs of the functions of a research and educational institution?

To begin to answer this and other questions the JISC KeepIt Project, which recently completed its 18-month programme, worked with four exemplars, including one of each of type of repository:

- research papers repository (NECTAR, University of Northampton)

- science data repository (eCrystals, University of Southampton)

- arts repository (UAL Research Online, University of the Arts London)

- educational and teaching repository (EdShare, University of Southampton)

We will discover more about these repositories in this article as we profile them in a revealing new light. The focus of the project was on the preservation concerns of these different repositories, and what each would choose to do when aware of the methods and tools for preservation [4]. As well as for scope and content, repositories were selected for their willingness to engage in these issues, rather than to indicate any special status. It is also instructive to recognise the differences in approach, as these have implications for a possible institution-wide composite repository.

One way of anticipating new forms of content is by auditing the institution using tools such as the Digital Asset Framework (DAF) [5][6]. Another way is monitoring the profile of content deposited in a repository, and this will be our focus here.

Profiles can be based on various factors, but one that matters for digital preservation is file format. Most computer users will at some time have been passed files they are unable to open on their machines. While this is not usually insurmountable it demonstrates again the process of change in types of digital content and formats. To combat the problem of format obsolescence [7] an emerging preservation workflow combines format identification, preservation planning and, where necessary, transformative action such as format migration [8].

Formats are therefore monitored for the purposes of digital preservation, and tools have been developed for this. One tool that has been adopted by three of the four KeepIt exemplars is the EPrints preservation ‘apps’ [9]. This bundles a range of apps, including the open source DROID file format identification tool from the National Archives [10], to present a format profile within a repository interface. Another tool that performs format identification, also validation and characterization, is JHOVE [11]. Both DROID and JHOVE can be found in the File Information Tool Set (FITS) from Harvard [12] and, Russian doll-like, FITS itself has been spotted in a format management tool as developers seek to generalise usage through targeted interfaces [13].

Format profiles are the starting point for preservation plans and actions. Such profiles can be produced and viewed from a dry, technical perspective, but these format profiles in effect reveal the digital fingerprints of the types of repositories they measure. The article will show this graphically by comparing the profiles of the four exemplars.

Format Profiles Past and Present

Format profiles of repositories are not new and have been produced using earlier variants on the tools [14]. What we have now are more complete and distinctive profiles for different types of repositories.

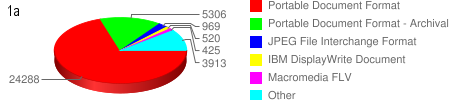

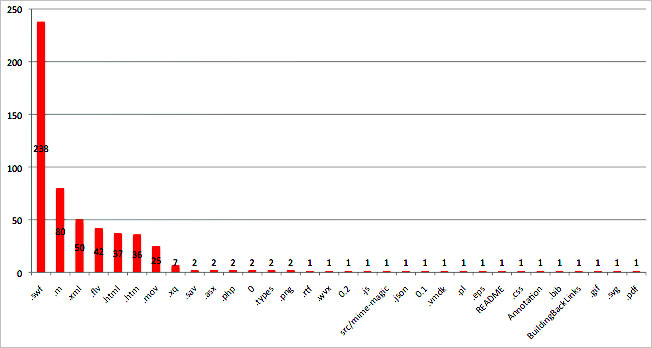

One obvious similarity we can note, however, between the KeepIt exemplars and earlier profiles, is the dominance in each profile of one format, that is, the total number of files in that format stored in the repository. This is followed by a power law decline in the number of files per format, the ‘long tail’. For open access research repositories the typical profile is dominated by PDF and its variants and versions (Figure 1a/1b). In the case of our KeepIt exemplars only one, the research papers repository, has this classic PDF-led profile. We can now reveal how the others differ, and thus begin to understand what preservation challenges they each face.

Figure 1a/1b: Example research repository format profiles dominated by PDF, from Registry of Open Access Repositories (ROAR), charts captured 22 December 2010: a, Hispana, aggregates Spanish repositories and other national resources; b, institutional repository, RepositoriUM, Universidade do Minho, Portugal

Producing Format Profiles

Before we do this, bear in mind how the profiles were produced. For the scale of repositories with which we have been working, this is now a substantial processing task that can take hours to complete.

For three repositories the counts include only accepted objects and do not include ‘volatile’ objects. The fourth (University of the Arts London) includes all objects, including those in the editorial buffer and volatiles. Repositories use editorial buffers to moderate submissions. Depending on the repository policy, there may be a delay between submission, acceptance and public availability. Volatiles are objects that are generated when required by the repository – an example would be thumbnail previews used to provide an instant but sizeably reduced view of the object.

These are growing repositories, so the profiles must be viewed as temporary snapshots for the dates specified. They are provided here for illustration. For those repositories that have installed the EPrints preservation apps, the repository manager is provided with regular internal reports including an updated profile, and will need to track the changes between profiles as well as review each subsequent profile.

Understanding and Responding to Format Profiles

We also need to understand some features of the tools when reviewing the results. In these results we have ‘unknown’ formats and ‘unclassified’ formats. Unclassified may be new files that have been added since a profile scan began (scans can take some time) or since the last full scan.

More critical for preservation purposes are files with unknown formats. To identify a file format a tool such as DROID looks for a specified signature within the object [15]. If it cannot match a file with a signature in its database it is classified as ‘unknown’. In such cases it may be possible to identify the format simply by examining the file extension (.pdf .htm .gif, etc.). In most cases a file format will be exactly what it purports to be according to this extension. The merits of each approach, by format signature or filename extension, can be debated; neither is infallible, nor has the degree of error been rigorously quantified for the different tools used. It is up to the individual repositories how they interpret and resolve these results.

The number of unknowns will be a major factor in assessing the preservation risk faced by a repository and is likely to be the area requiring most attention by its manager, at least initially until the risk has been assessed. We believe that in future it will be possible to quantify the risk of known formats [16], and to build preservation plans to act on these risks within repositories [17].

For formats known to specialists but not to the general preservation tools, it will be important to enable these to be added to the tools. When this happens it will be possible for the community to begin to accumulate the factors that might contribute to the risk scores for these formats. As long as formats remain outside this general domain, it will be for specialists to assess the risk for themselves. We will see examples of this in the cases below.

Producing format profiles is becoming an intensive process, and subsequent analysis is likely to be no less intensive.

Science Data Repository (eCrystals, University of Southampton)

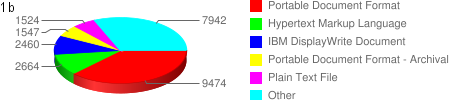

A specialised science data repository is likely to have file types that a general format tool will fail to recognise. For this repository of crystal structures we anticipated two such formats – Crystallographic Information File (CIF) and Chemical Markup Language (CML) – and signatures for these formats were added to the identification tool. What we can see in this profile is how successful, or not, these signatures were. That is, successful for CIF, but only partially successful for CML.

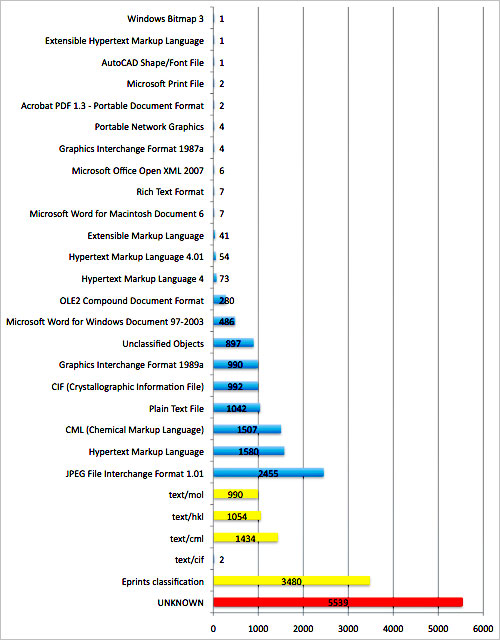

For this repository, which uses a customised version of EPrints and therefore has not so far installed the preservation apps, we ran the tool over a copy of the content temporarily stored in the cloud. Figure 2 shows the full profile for this repository, including unknowns (in red, 5000+), those formats not identified by DROID but known to EPrints (showing both the total and the breakdown in yellow (see text/* files)), as well as the long tail of identified formats. All but two CIF files were identified by DROID. Had all the instances of CML been recognised it would have been the largest format with most files (adding the yellow and blue CML bars), but almost half were not recognised by DROID.

Figure 2: eCrystals: full format profile including formats ‘unknown’ to DROID and the repository (in red), the breakdown of those classified by the repository (yellow bars), as well as the long tail of formats classified by DROID. Chart generated from spreadsheet of results (profile date 1 October 2010).

As it stands, the format with the largest number of files known to DROID was an image format (JPEG 1.01). We will see this is a recurring theme of emerging repository types exemplified by our project repositories. Also with reference to the other exemplar profiles to follow, it will be noticeable that this profile appears to have a shorter long tail than others. However, in this case we can see that ‘unknown’ (to DROID and EPrints) is the largest single category, and when this is broken down it too presents a long tail (Figure 3) that is effectively additive to the tail in Figure 2. These include more specialised formats, which might be recognised by file extension.

Figure 3: eCrystals ‘unknown’ formats by file extension (profile date 1 October 2010).

As explained, clearly these unknowns will need to be a focus for the repository managers, although in preliminary feedback they say that many of these files are “all very familiar, standard crystallography files of varying extent of data handling that often get uploaded to ecrystals for completeness.” This is reassuring because file formats unknown to system or manager or scientists could be a serious problem for the repository. Even so, as long as such formats remain outside the scope of the general format identification tools, the managers will need to use their own assessments and judgement to assure the longer-term viability and accessibility of these files.

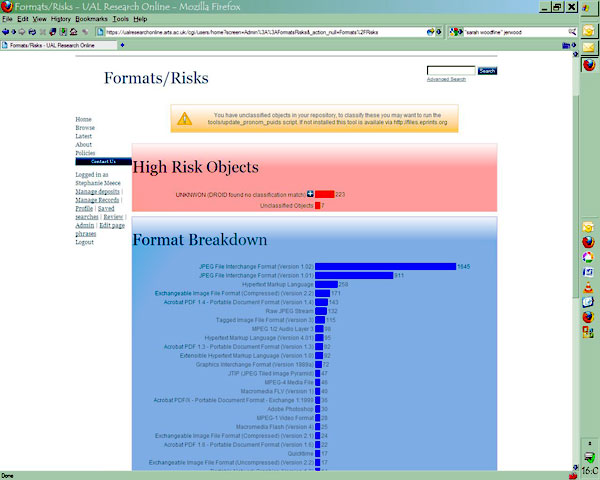

Arts Repository (University of the Arts London)

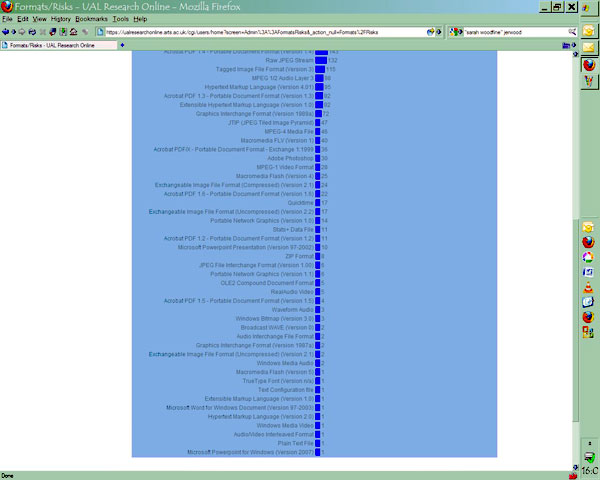

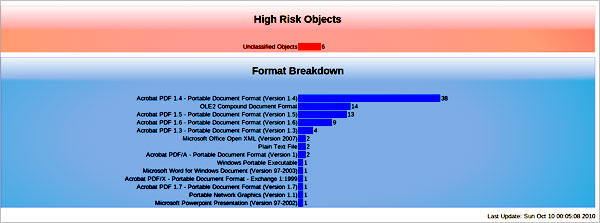

What is the largest file type in an arts repository? Perhaps unsurprisingly it is an image format, in this case led by JPEGs of different versions. As can be seen in Figure 4a (or Figure 4a large format), the number of unknowns, highlighted among the High Risk Objects, is the fourth largest single category in this profile and so requires further investigation. Once again there is a long tail (Figure 4b or Figure 4b large format ).

Figure 4. Format/Risks screen for UAL Research Online Repository: a, top level; b, long tail. These screenshots of the profile were generated by the repository staff from the live repository using the installed tools. (Date 13 September 2010).

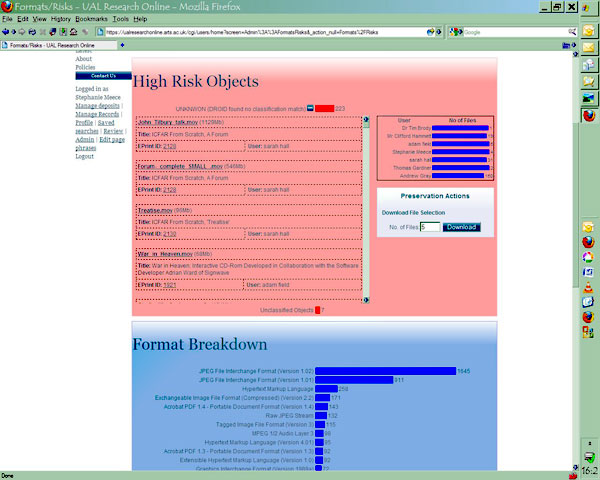

First indications in Figure 5, showing the expansion of the high risk category, suggest many of them will turn out to be known formats but which have not been recognised by DROID. It may be possible to resolve and classify many of them by manual inspection, the last resort of the repository manager to ensure that files can be opened and used effectively.

Figure 5: High-risk objects (top level examples) in UAL Research Online Repository. This profile was generated by the repository staff from the live repository using the installed tools. (Date 13 September 2010.)

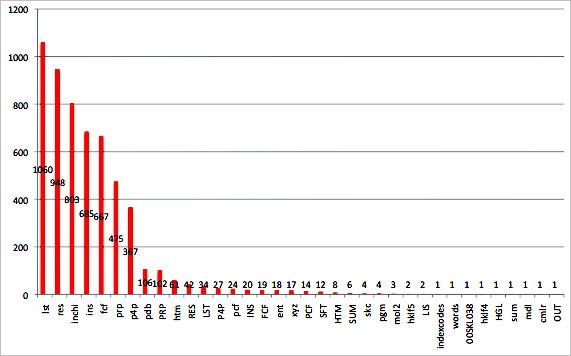

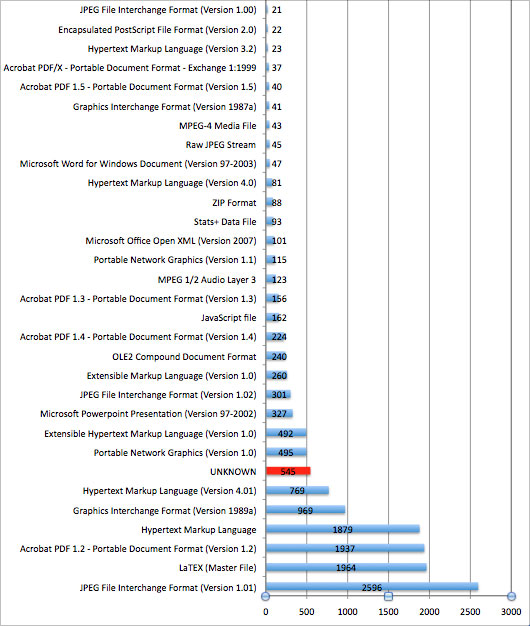

Teaching Repository (EdShare, University of Southampton)

The first notable feature of the EdShare profile (Figure 6) is that the largest format is, again, an image format. Evidently, like an arts repository (perhaps predictably) and like a science data repository (less predictably), it seems the emphasis of a repository of teaching resources may be visual rather than textual.

Figure 6. EdShare: Largest formats by file count (top half of long tail). Chart generated from spreadsheet of results (profile date 14 October 2010).

Another feature of the profile is the classification of LaTEX (Master File), the second largest format in this profile. Until now this format was unknown to DROID, but a new signature was created and added to our project version of DROID, in the same way as for CIF/CML (and was submitted to The National Archives (TNA) for inclusion in the official format registry). The effect of this was to reduce the number of unknowns from nearly 2,500 to c. 550, and thus instantly both to clarify and reduce the scale of the challenge.

As usual with the long tail, preservation planning decisions have to be made about the impact and viability of even infrequent formats. For reference, Table 1 shows the formats not included among the largest formats by file count in Figure 6.

| Plain Text File | 20 |

| Rich Text Format (Version 1.7) | 17 |

| Windows Bitmap (Version 3.0) | 15 |

| Acrobat PDF 1.6 - Portable Document Format (Version 1.6) | 15 |

| Waveform Audio | 12 |

| Document Type Definition | 11 |

| Macromedia FLV (Version 1) | 11 |

| MPEG-1 Video Format | 9 |

| Icon file format | 9 |

| LaTEX (Sub File) | 9 |

| XML Schema Definition | 8 |

| Macromedia Flash (Version 7) | 8 |

| Windows Media Video | 6 |

| Extensible Hypertext Markup Language (Version 1.1) | 5 |

| Rich Text Format (Version 1.5) | 3 |

| TeX Binary File | 3 |

| Acrobat PDF 1.1 - Portable Document Format (Version 1.1) | 3 |

| Java Compiled Object Code | 2 |

| Encapsulated PostScript File Format (Version 3.0) | 2 |

| Exchangeable Image File Format (Compressed) (Version 2.2) | 2 |

| Scalable Vector Graphics (Version 1.0) | 2 |

| Adobe Photoshop | 2 |

| Microsoft Web Archive | 2 |

| Audio/Video Interleaved Format | 2 |

| JTIP (JPEG Tiled Image Pyramid) | 1 |

| Comma Separated Values | 1 |

| OS/2 Bitmap (Version 1.0) | 1 |

| Acrobat PDF 1.7 - Portable Document Format (Version 1.7) | 1 |

| PHP Script Page | 1 |

| Microsoft Word for Windows Document (Version 6.0/95) | 1 |

| Quicktime | 1 |

| Hypertext Markup Language (Version 2.0) | 1 |

| Applixware Spreadsheet | 1 |

| PostScript (Version 3.0) | 1 |

Table 1: Long tail of formats by file count in EdShare

Again, the unknowns present a potent challenge. Figure 7 is a breakdown of what we think we can tell from file extensions. Unlike the case of unknowns in eCrystals, here there was less anticipation of specialised formats that were unlikely to be found in a general format registry, so this list is a something of a revelation. In many of these cases an error in the file may be preventing recognition of an otherwise familiar format. Here we can see extensions such as Flash files, various text-based formats such as HTML, CSS, etc., which may be malformed, and possibly some images. In such cases the relevant file should be identified and an attempt made to open it with a suitable application. In this way it may be possible to begin to assess the reasons for non-recognition, to confirm the likely format, and take any action to repair or convert the file if necessary. Files with unfamiliar extensions (.m) will need particular attention.

Figure 7: EdShare: Unknown formats (profile date 14 October 2010).

Another feature of this repository’s format profile not illustrated here is the difference when the profile is based on file size (the amount of storage space consumed) rather than file count. In this case the largest format by file size remains JPEG 1.01, but the next largest file types are all MPEG video formats, which is not so evident from Figure 6 and Table 1. It is not hard to understand why this might be: video files tend to be larger than text files or other format types. At first sight the profile by file count might have the stronger influence on preservation plans, but this further evidence on file size might be used strategically as well.

Research Papers Repository (University of Northampton)

Figure 8 (or Figure 8 large format) is a classic, PDF-dominated profile of a repository of research papers. Although an apparently small repository, what this shows is a repository that has so far focused on records-keeping rather than on collecting full digital objects. We have seen already how investigations to expand the scope of this repository have begun [6]. There is nothing in this profile that would surprise the repository manager. It acts as confirmation, a snapshot of the repository and can be viewed as a platform for deciding where the repository should head in future. The tools will help the repository manager to monitor growth and the implementation of future plans.

Figure 8: NECTAR format profile from live repository screenshot

Format Profiling: Not Just Preservation, But Knowing What You Have

Much of the impetus for format profiling and management has been to serve a preservation workflow based on the recognition that digital formats can become obsolete. Rosenthal has challenged this approach on the basis that format obsolescence is the exception rather than the norm, at least since the mid-1990s and the wide use of networked services such as the Web [18]. If correct, this view has implications in particular for the economics of preservation based on a format workflow, and the case is made for a more efficient re-allocation of resources to other preservation activities.

Would this make format profiling redundant? It looks unlikely for large digital repositories of heterogeneous digital formats or those that acquire content by author self-archiving, such as some we have just profiled. The starting point for preservation is to know what content you have, not just in terms of bibliographic metadata such as title, author, etc., but also in terms of technical metadata, including file formats. The methods we have demonstrated are currently the best means of extracting, updating and monitoring this information efficiently.

The economic question about implementing a full preservation workflow suggests that resources should initially be weighted to the earlier stages such as format identification, while the questions on what to do with identified formats – e.g. migrate or not – will have to be answered by preservation planning. This has typically been the missing link in preservation workflows that pre-emptively migrate formats. A preservation planning tool such as Plato has been integrated into repository software [17], and provides a more flexible approach to format acquisition than has been proposed, for example, for the Wellcome Library [19]. When preservation planning is supported by comprehensive, open format registries [20], then it should be possible for a repository with a clear policy or mandate and costing plan to specify the preservation workflow that suits its requirements.

Conclusion

Digital and institutional repositories are changing, and rapidly growing repositories targetting new types of digital content, including data and teaching materials, from science to the arts, now complement the established research papers repository. For the first time we have been able to compare and contrast these different repository types using tools designed to assist digital preservation analysis by identifying file formats and producing profiles of the distribution of formats in each repository.

While past format profiles of repositories collecting open access research papers tended to produce uniform results differing in scale rather than range, the new profiles reveal potentially characteristic fingerprints for the emerging repository types. What this also shows more clearly, by emphasising the differences, are the real preservation implications for these repositories based on these profiles, which could be masked when all profiles looked the same. Each exemplar profile gives the respective managers a new insight into their repositories and careful assessment will lead them to an agenda for managing the repository content effectively and ensuring continued access, an agenda that will be the more clearly marked for recognising how the same process produced different results for other types of repository.

This agenda will initially be led by the need to investigate digital objects for which the format could not be identified by the general tools, the ‘unknowns’. We have seen that science data repositories, and even less obviously specialised examples, can produce large numbers of unknowns. These are high-risk objects in any repository by virtue of their internal format being unknown, even though on inspection many may turn out to be easily identified and/or corrected. For the known formats, especially the largest formats by file count, these profiles show where effort is worth expending on producing preservation plans that will automate the maintenance of these files. Based on these exemplars, all repositories with substantial content are likely to produce format profiles displaying a long tail. An intriguing finding of this work is that the emerging repository types, rather than open access institutional repositories founded on research papers, are dominated by visual rather than textual formats.

All these exemplars either are, or plan to become, institutional in scope even though limited to a specified type of content. One original idea that motivated the KeepIt Project was that truly institutional repositories are, one day, likely to collect and store digital outputs from all research and academic activities, such as those represented by these exemplars. Thus, combined, the exemplars might represent the institutional repository of the future. It is worth bearing in mind how the combined format profiles might look, and the consequent implications for preservation, when contemplating the prospect.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the exemplar repositories for allowing us to reproduce these profiles. The KeepIt Project was funded by JISC under the Preservation strand of its Information Environment programme 2009-2011.

References

- Roberts, R. J., et al., “Building A ‘GenBank’ of the Published Literature”, Science, Vol. 291, No. 5512, 23rd March 2001, 2318-2319

http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/291/5512/2318a - Hitchcock, S., “The effect of open access and downloads (‘hits’) on citation impact: a bibliography of studies”, Last updated 6 December 2010; first posted 15 September 2004

http://opcit.eprints.org/oacitation-biblio.html - Salo, D., “Preservation and institutional repositories for the digital arts and humanities”, Summer Institute for Data Curation, University of Illinois, 21 May 2009, slides

http://www.slideshare.net/cavlec/digital-preservation-and-institutional-repositories - Pickton, M., et al., “Preserving repository content: practical steps for repository managers”, Open Repositories 2010, Madrid, July 2010

http://or2010.fecyt.es/Resources/documentos/GSabstracts/PreservingRepositoryContent.pdf

See also KeepIt preservation exemplar repositories: the final countdown, Diary of a Repository Preservation Project, November 30, 2010,

http://blogs.ecs.soton.ac.uk/keepit/2010/11/30/keepit-preservation-exemplar-repositories-the-final-countdown/ - Data Asset Framework Implementation Guide, October 2009 http://www.data-audit.eu/docs/DAF_Implementation_Guide.pdf

- Alexogiannopoulos, E., McKenney, S., Pickton, M., “Research Data Management Project: a DAF investigation of research data management practices at The University of Northampton”, University of Northampton, September 2010

http://nectar.northampton.ac.uk/2736/ - Pearson, D., Webb, C., “Defining File Format Obsolescence: A Risky Journey”, International Journal of Digital Curation, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2008

- Brown, A., “Developing Practical Approaches to Active Preservation”, International Journal of Digital Curation, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2007

http://www.ijdc.net/index.php/ijdc/article/view/37 - EPrints preservation apps: from PRONOM-ROAR to Amazon and a Bazaar, Diary of a Repository Preservation Project, 15 November 2010

http://blogs.ecs.soton.ac.uk/keepit/2010/11/15/eprints-preservation-apps-from-pronom-roar-to-amazon-and-a-bazaar/ - Using DROID to profile your file formats, The National Archives, undated

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/using-droid-to-profile-your-file-formats.pdf - Abrams, S., Morrissey, S., Cramer, T., “ “What? So What”: The Next Generation JHOVE2 Architecture for Format-Aware Characterization”, International Journal of Digital Curation, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2009

http://www.ijdc.net/index.php/ijdc/article/view/139 - File Information Tool Set (FITS), Google code http://code.google.com/p/fits/

- Thomas, S., scat @ Gloucestershire archives, futureArch blog, 11 March 2010

http://futurearchives.blogspot.com/2010/03/scat-gloucestershire-archives.html - Brody, T., Carr, L., Hey, J.M.N., Brown, A., Hitchcock, S., “PRONOM-ROAR: Adding Format Profiles to a Repository Registry to Inform Preservation Services”, International Journal of Digital Curation, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2007

http://www.ijdc.net/index.php/ijdc/article/view/53/ - Brown, A., “Automatic Format Identification Using PRONOM and DROID”, Digital Preservation Technical Paper 1, The National Archives, 7 March 2006 http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/aboutapps/fileformat/pdf/automatic_format_identification.pdf

- Tarrant, D., Hitchcock, S., Carr, L., “Where the Semantic Web and Web 2.0 meet format risk management: P2 registry”, International Journal of Digital Curation, accepted for publication, 2011, also in iPres2009: The Sixth International Conference on Preservation of Digital Objects, October 5-6, 2009, San Francisco http://eprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/17556/

- Tarrant, D., Hitchcock, S., Carr, L., Kulovits, H., Rauber, A., “Connecting preservation planning and Plato with digital repository interfaces”, in 7th International Conference on Preservation of Digital Objects (iPRES2010), 19-24 September 2010, Vienna

http://eprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/21289/ - Rosenthal, D., “Format Obsolescence: Assessing the Threat and the Defenses” Library Hi Tech, 28 (2), 195-210, 2010 http://lockss.stanford.edu/locksswiki/files/LibraryHighTech2010.pdf, see also “The Half-Life of Digital Formats”, dshr’s blog, November 24, 2010

http://blog.dshr.org/2010/11/half-life-of-digital-formats.html - Thompson, D., “A Pragmatic Approach to Preferred File Formats for Acquisition”, Ariadne, No. 63, 30 Apr 2010

http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue63/thompson/ - Thomas, D., “Linked data and PRONOM”, The National Archives Labs, October 2010

http://labs.nationalarchives.gov.uk/wordpress/index.php/2010/10/linked-data-and-pronom/