ECLAP 2013: Information Technologies for Performing Arts, Media Access and Entertainment

Marieke Guy reports on the second international conference held by ECLAP, the e-library for performing arts.

The beautiful city of Porto was the host location for ECLAP 2013 [1], the 2nd International Conference on Information Technologies for Performing Arts, Media Access and Entertainment. Porto is the second largest city in Portugal after Lisbon and home of the Instituto Politécnico do Porto (IPP), the largest polytechnic in the country, with over 18,500 students. IPP has 7 different faculties, the School of Music and Arts - Escola Superior de Música, Artes e Espectáculo (ESMAE) [2] - is one of the two original schools established when IPP was founded in 1985. The Teatro Helena Sá e Costa, ESMAE’s main theatre, provided a fitting location for a conference looking at IT innovation within the cultural heritage area, and the performing arts in particular.

As an outsider to the ECLAP scene and a relative newcomer to the area of IT and performing arts I was unsure of what to expect from the conference but keen to learn more about the opportunities and challenges facing those working in this area. The overview of the ECLAP Project, given by Paolo Nesi, Professor of Computer Science Department at the University of Florence, gave some useful insights into project work so far.

ECLAP [3] was co-funded by the European Union ICT Policy Support Programme, as part of the Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme, to create a social network and media access service for performing arts institutions across Europe. It has done this by establishing an e-library for performing arts and a best practice network of experts and services working in performing arts institutions in Europe.

The e-library currently contains more than 100,000 content objects (images, videos, documents, audio files, ebooks, ePub documents, animations, slides, playlists, collections, 3D objects, Braille music, annotations, etc) from more than 30 European institutions. It is powered by a large semantic model which collects content from over 35 providers and manages metadata in 13 different languages. The structure of this model was covered in more detail by Pierfrancesco Bellini, University of Florence, later on in the day during his talk on a linked open data service for performing arts. Bellini explained that they have been using RDF standards and making vocabularies available as linked open data whenever possible. The main vocabularies they have been working with are Dublin Core (DC), Friend of a Friend (FOAF), Creative Commons (CC) and basic geo vocabularies. They have found that providing linked open data improves the user experience by adding contextual information and allows the data to be seen in a more visual way. A specific vocabulary has been designed for the project and is available for reuse [4].

The ECLAP Project has also developed a number of tools to aggregate and enrich accepted content, such as MyStory player, an audiovisual annotation tool [5], which is also one of the tools that comprises Europeana Professional [6]. The eventual aim is to deliver over 400,000 objects that cover the ‘richness and value of the European performing arts heritage’ to Europeana [7], the European Digital Library.

The 2013 conference was primarily an attempt to pull together those with knowledge of ECLAP activities and performing arts research practitioners into one space. The focus was on how technologies and innovations produced for digital libraries, media entertainment and education can be exploited in the field of performing arts but also on new innovations developed specifically for the performing arts.

At times the 3-day event felt more like an ECLAP Project meeting than an international conference, there were relatively few participants and many of the delegates had obviously been working together recently. The informality of the event sometimes left me a little confused, the programme itself, which had only been shared online the week before, was fairly random, with talks within the same tracks ranging from highly technical to general. There were also some very long days and the event could have benefited from tighter scheduling and stricter chairing – we seemed to be permanently running 30 minutes late. However once I had accepted that this appeared to be customary, I really enjoyed the conference. There were some inspiring talks and the days were spiced up with amazing live performances from the ESMAE students and some really friendly, productive discussion.

Some of the key themes that I drew from the event relate to:

- Tensions between archiving old work and creating new work (that employs new ICT approaches). Much discussion in this area was around ‘where should the money go?’ Is it just about optimising what we already have or research for the future?

- How do we digitally preserve the visual arts - is just about reproducibility or is it about much more? How can we capture audience interaction? etc

- Issues around terminology – do we fully understand what is meant by performance art, performing arts, dance, movement? How can we use IT the better to describe the performing arts world? Can we use better metadata, more detailed ontologies, can we improve dance notation?

- Cross-discipline work – what can the performing arts learn from other disciplines? What innovation in this area can be applied to other areas?

Here are overviews of my choice presentations.

Culture and Creativity in the Digital Realm: A Boost from the Past

The opening plenary was delivered by Luis Ferrão from the Creativity Unit, a relatively new unit formed in July 2012 by the European Commission, DG Communications Networks, Content and Technology. Ferrão explained that the EU has competence in the area of culture and it has made a commitment (through documents like the Lisbon Treaty) to ‘support, co-ordinate or complement’ cultural heritage work. However what exactly is meant by culture is often a matter for discussion. Ferrão chose to define it using the well-known T.S. Eliot quote: ‘Culture…that which makes life worth living’.

While cultural heritage has consistently been on the EC’s agenda, it has now become apparent that the move to a digital realm has been a game changer, with emphasis moving to interaction and social communities and away from traditional approaches. The new vision holds that: ‘culture and creation is an incremental, mutually enriching process’. The forthcoming strategy for Europe, Horizon 2020, sees digitisation as key, but also has an open data element. The main obstacles to this are (in no particular order):

- lack of investment (especially in the area of research and development);

- problems surrounding digital literacy;

- fragmented digital markets;

- interoperability issues; and

- cyber-criminality.

Despite these issues it is clear that digital access to cultural heritage breathes new life into material from the past and turns it in to a formidable asset: the digital economy is a virtuous circle. The core service behind current efforts is Europeana – launched in 2008 – into which ECLAP feeds.

Ferrão went on to highlight some other EC work being carried out in this area such as the 2011 New Renaissance report and the more recent report on orphan works. A new project called ARROW [8] is looking specifically at improving the obstacle of rights clearance to digital material.

After his talk, Ferrão answered some questions around how institutions can get access to more R&D funding in the area of performing arts. He explained that Horizon 2020 is offering around €80 billion (though this figure is likely to be slightly reduced) for ICT innovation. The best successes will come from pooling resources and using the instruments already there.

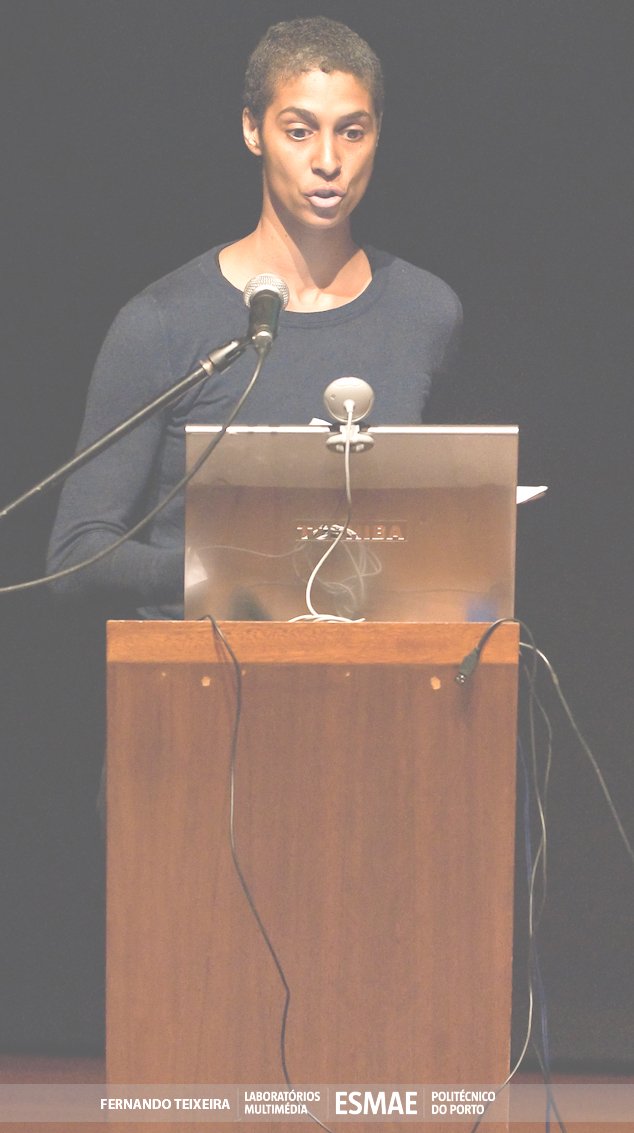

Figure 1: Bertha Bermudez, researcher, performer and project manager, education at ICK Amsterdam

Multimodal Glossaries: A New Entrance to Artistic Insights of Dance Praxis

Bertha Bermudez, researcher, performer and project manager at ICK Amsterdam, gave a really inspiring talk on multimodal representations of dance, ie ways to record the dance process. She asked us to consider the crossroad between dance and digital tools, and how we can move forward with developing these tools.

Bermudez explained that there is interest from artist and soci-cultural institutions around the relations between experience, embodiment and technology. This interest also expands to the relationship between dance and cognitive science, technology and other more established scientific disciplines. Dance is an expert field on human movement, yet in the past dancers haven’t revealed their methods or their tacit knowledge. It is almost like the body was a container of knowledge with copyright. More recently artists have begun to want to share their knowledge and there has also been a shift in paradigm around how artists go about it.

These ideas were explored further by a look at some recent projects. For example SynchronousObjects [9] examines the organisational structures found in William Forsythe's dance One Flat Thing. It does this by translating and transforming the dance into new objects, visualising dance using techniques from a variety of disciplines. The project asks: ‘what does physical thinking look like?’ Motion Bank [10] is another Forsythe-related project that looks into choreographic practice through the creation of online digital scores in collaboration with guest choreographers. Bermudez also mentioned the Whatever dance toolbox [11], a set of software tools designed for the analysis and development of dance and movement.

Bermudez finished by explaining that digital technologies offer the opportunity to explore new modes of representation. All layers of kinetics, oral transmission and experience can be shared. Dance has changed to become a body which can be enhanced through new media while the body itself can be a script from which other people can read.

Feature Matching of Simultaneous Signals for Multimodal Synchronisation

Dr Kia Ng from the School of Computing and the School of Music at the University of Leeds continued the exploration of how you can capture dance. At Leeds they are looking at capturing sensory data using multimodal analysis and gestural interfaces. One good example here is in the area of sport where the use of music can create a steady rhythm, improved mood and reduced fatigue. Ng has worked on a number of European and international projects such as iMaestro [12], which developed interactive multimedia environments for technology-enhanced music education. Some of the novel solutions for music training use tools like 3D augmented mirrors, kinect devices for hand gestures and the ability to ‘practise with yourself’ using interactive composition.

Digital Preservation for the Performing Arts

David Giaretta, Director of the Alliance for Permanent Access to the Records of Science in Europe Network and former co-director of the Digital Curation Centre (DCC) took me back to familiar ground by looking at ways that we can apply digital preservation methods to the performing arts. Giaretta admitted to having a science background, not an arts background, but explained that digital preservation has much to offer all disciplines. He stated, albeit with tongue in cheek, that digital preservation itself is easy as long as you can provide money forever, and that it was always possible to test claims about repositories as long as you live a long time. A more pragmatic approach would be to carry out the preparation now so that, in five to ten years, decisions can be made about what to keep. This was important because ‘things change’; for example, hardware and software change, the environment we work in changes (it is difficult to know what the dependencies are on the Internet) and tacit knowledge changes (people leave). The result is that things become unfamiliar. Unfortunately politicians are not keen to spend money on future generations (preservation included) because young people don’t vote or pay taxes! In the past claiming ‘this is being preserved’ was untestable.

Giaretta then gave an overview of the Open Archival Information System (OAIS) model. The model had originally been developed as a way of ‘testing’ preservation to ensure digitally encoded information was understandable and usable over the long term. OAIS introduces some fundamental concepts and ways of talking about digital preservation and suggests that you can test for preservation by ‘being able to do something’ with whatever you have preserved. At a basic level you can make sure you preserve the bits, but real preservation is about future use. Giaretta noted that we can’t command people to use particular formats, we have to be able to survive all types of encodings. Through work on the CASPAR Project [13] a better understanding has been achieved around the digital rights to preserved data. The project also found that digital preservation concerns arose across disciplines; there were common threats. Part of the project work was looking at services that could benefit different disciplines. In the performing arts there is a need for preservation, usability and re-performability (often another artist has to be able to recreate the performance). Many of the preservation tests had used re-performability as a marker, though discussions around this in the Q&A suggest that it isn’t always an appropriate indicator. For example, how do you preserve the performers’ interaction with the audience?

Figure 2: Panel: From left to right: Paolo Nesi (ECLAP coordinator, Firenze University), Carlos Ramos (Vice President of the Porto's Polytechnic Institute), Francisco Beja (President of ESMAE - Superior School of Music and Performing Arts - Porto)

The Challenge of the Inter in the Preservation of Cultural Heritage

Possibly my favourite presentation of the conference was presented by Sarah Whatley, Professor of Dance at Coventry University. Whatley continued the discussion stimulated by David Giaretta’s talk on ‘what can we preserve?’ and explained how many artists are creating work that defy digital modes of preservation, work that is hugely difficult to archive. In the past the physical dance has rarely survived beyond the moment, yet the event can be captured in ephemera such as flyers, invitations, posters, etc, and some of them may have been available for scholarly analysis. However at the end of the last century people began to worry about loss of dance and the politics of dance preservation and reconstruction. Recently there has been more interest in re-enactment and returning to old works. This has been described by André Lepecki in the journal article “The Body as Archive: Will to Re-Enact and the Afterlives of Dances” [14] as the ‘current will to archive’.

Over the last decades dance has been engaging with the digital environment, but performance events have often evaded capture in traditional ways, primarily because people are unsure of how exactly they can be archived. These events are always in a state of ‘becoming’, the artist is largely invisible and they offer many difficulties for archivists. The Gateway to Archives of Media Art (GAMA) [15] has embraced some of these challenges. They have felt that using film as a means of capturing work may be a poor representation and that technology is more than just a tool for humans. The archive attempts to interact with work. Some believe that for a dance work to exist it should be performable and not just one moment in time – that is, you need to capture how the dance is done; it needs to be repeatable. This means that the conditions need to be recorded too, yet the audience is an active part of the work, this can’t be recorded. Whatley explained that it is not just archivists who are looking at this area, performers are too. She gave some examples of performing artists who are responding to new IT, for example using Mocap (motion capture). Whatley concluded by noting that technical advancements haven’t fully grappled with problems of how we capture dance, yet some documentation is better than none. However it is important to see that artists can help with this process. She ended with a quote from Christopher Salter: ‘Performances do things to the world, conjuring forth environments that emerge simultaneously with the individuation of the technical or living being.’

The TKB Project: Creative Technologies for Performance Composition, Analysis and Documentation

Carla Fernandes from the University of Lisbon gave a presentation on linguistic annotation and the relationships between gestures and language. Fernandes has been working on the TKB Project [16], an extensive and trans-disciplinary project aiming at the design and construction of an open-ended multimodal knowledge-base to document, annotate and support the creation of contemporary dance pieces. The project is looking at the interstices between linguistics and performing arts studies by considering three different moments of analysis: pre-rehearsal, the rehearsal period (oral transmission, interaction between performers) and the première of a piece. At each of these stages multi-modal activity takes place: body movement, language, visuals, multimedia resources, sound and haptics (non-verbal communication involving touch).

Dance in the World of Data and Objects

Also considering the art of dance, Katerina El Raheb from the University of Athens asked the question how can we make data on dance searchable? Her work has involved looking at various digital information systems used for indexing and analysing, and at available ontologies. Much current practice involves the building upon Labanotation (LN) or Kinetography Laban, a notation system for recording and analysing human movement. However ‘meaning is more than words and deeper than concepts’ and so El Raheb is exploring other approaches. She has found that the W3C OWL-2 [17] ontology, although it is not a dance analysis model or a new notation system, could work well as DanceOwl. Its main advantages surround reasoning and expression of rules; it is also extensible, searchable, uses understandable terms and considers temporal modelling and human body representation. However, as El Raheb explained, a score is only a script and remains open to different interpretations, it is just one part of the documentation. There is a difference between motion capture (capturing a moment in time) and dance script (creating a script so someone can carry out the dance). El Raheb’s work considers questions like ‘What is a dance? What is movement? What characterises it? How can this be segmented into moves and steps?’ One interesting area of work is where she has tried to apply cultural heritage models to dance, for example work > expression > manifestation > item (whereby a work might be Hamlet, an expression might be a Portugese version, a manifestation might be a particular version and an item might be the DVD copy).

To conclude, El Raheb explained that dance is not an object, nor a concept. We can annotate objects related to it and we can use concepts related to dance analysis to prescribe and describe its movement. These approaches could allow dance knowledge to become more accessible to many more.

There followed some really honest discussion on the point of research and whether researchers complete their work decide that it is ‘useless’ (note this discussion wasn’t directly related to El Raheb’s research). The discussion brought home the need to avoid technology for technologies case and for researchers to bear in mind who they are addressing with their research and what they are providing for the performers.

MultiStage: Acting across Distance

Fei Su of the University of Tromsø, Norway gave a presentation on creating multistages. He and his team have been looking at ways of enabling actors in different locations to act and interact together and so appear as if on one stage. Supporting acting across distance can make for interesting new performances but it can also make it possible for actors to rehearse together when not physically in the same place. However multistage acting is not straight-forward: it requires hardware and software systems, radio and wired networks, sensors to capture the actors, and computers to receive and analyse the data. The main hardware used are kinect motion sensing input devices designed by Microsoft for the Xbox 360 console. The separate stages must then be ‘bound together’. The main challenges are dealing with delays (distance always causes some delay in video streaming) and issues with causality (an event must happen before it can be observed and reacted to – so more delays). There are times when synchronisation is critical, for example if actors are dancing together, and times when it isn’t so critical. The research team are working on masking the effects of the delays using the idea of a ‘remote handshake’ as a test. The process is helping them ascertain how much delay is acceptable.

The Space Project: Update and Initial Findings

The final keynote on Day Three was from Amanda Rigali, Director of Combined Arts and Touring at the Arts Council England, on the digital arts service The Space [18]. Rigali began by explaining that Arts Council England currently fund 680 arts organisations. Their current digital capacity has been recently described as follows: 54% primarily use digital to market, 38% have embraced digital media in their daily work – so have interactive events, etc, 8% see digital media as their core creative purpose. Recently there have been real efforts to increase digital use and embed it more within arts organisations driven by the Arts Council England belief that digital material drives people to the live experience.

The Space was originally set up as part of the Cultural Olympiad, it was not an academic project and no academics have been involved in the service so far. The pilot service was Arts Council-managed and BBC staff were seconded to the project to help with technical aspects. It was developed by a limited number of staff run from a box room at BBC TV studios. There was a core technical and editorial team of five people, supported by other BBC staff. Arts Council England is the legal owner of the platform, which has caused a number of legal issues.

From the start, the Space was envisaged not just as an archive service but as being about new digital work. The team wanted to show full performances across the breadth of arts. There was a need to offer new perspectives, rich content, a wide theatrical range, light curated and moderated feel, and to see it to work on as many different browsers as possible. Work from established and emerging companies contributed to the effort.

Agreement for the project was secured in November 2011 and then an open application lottery programme was launched to find new artists to create work for the space. There were 730 expressions of interest and 116 were invited to submit full applications. Rigali explained that one of the deciding factors here was that the ideas had to be achievable. 53 projects eventually received funding of which 51 successfully delivered work, a very high achievement rate. A further 15 commissions from other arts funding bodies along with additional work and archive material (from the Arts Council, BBC, and the British Film Institute) have since been added. The Space was launched on 1 May 2013 and is accessible from several platforms including TVs, phones and tablets.

Rigali showed some really inspiring instances of work. For example the Place des Anges was a pop-up event which took place in Piccadilly Circus. A circus was set up for just one day, the event wasn’t publicised, it was just for anyone who happened to be there. Some works were incredibly impressive: the Globe received one commission for 37 full-length Shakespeare plays in different languages. It was important that all work was to be delivered for a new and global audience. This naturally resulted in translation issues and BBC linguists had to get involved.

The biggest challenge for the project has been resourcing: time and people. There was only one curator for the site and the 5-person-team had a very tight timescale in which to turn around content. As the project has an Arts Council and BBC stamp, this has always meant high user expectations too. There have also been some technical challenges, for example offering technical support to non-standard projects and keeping to accessibility guidelines. Alongside these issues has been the ongoing problem of rights clearance. Rigali pointed out that it was interesting that artists are often concerned about rights to their own work, yet frequently fail to consider the rights to the work of others that they reuse.

The site has had over 1.3 million visits, an average of 40,000 visits per week, 43% of which are visits from outside the UK. One particularly successful area has been the John Peel record collection which provides ways to view his collection of around 25,000 vinyl albums.

The Q&A time gave Rigali an opportunity to talk about the other work in this area, such as the Routledge Performance Archive and Digital Theatre Plus. Part of her initial work had been to justify state funding by market failure; the Space, by being a free resource, is different from everything else out there.

Conclusion

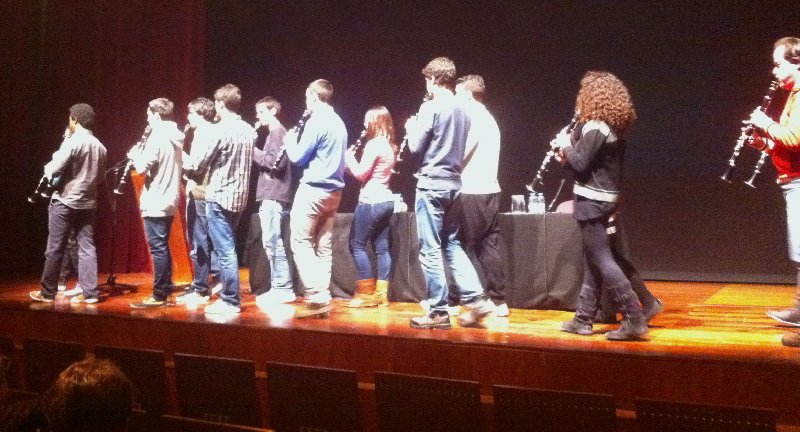

There were many other interesting sessions at ECLAP that I haven’t mentioned here including a best practice session on trust and quality in cultural heritage digital libraries. These talks looked at ways to preserve authenticity, apply metadata and assess metadata quality. There was also a best practice session on educational services for the performing arts covering some excellent resources like the Cuban Theatre Digital Archive and a general discussion on how to deal with IPR issues for performing arts content. During the breaks there was a poster exhibition and we were also entertained with several short films filmed and directed by ESMAE students. At one point, a conga of oboe players came into the theatre playing their ‘practice tunes’. The inclusion of performance art gave a freshness and energy to the event and also made the point well that there is nothing quite like live performance. Capturing, archiving, sharing, managing and interacting with this energy using IT is a big challenge.

All the talks at ECLAP were captured by Camtasia and should be available from the ECLAP site soon along with PDF versions of the slides and papers from the talks.

References

- ECLAP 2013: the 2nd International Conference on Information Technologies for Performing Arts, Media Access and Entertainment http://www.eclap.eu/drupal/?q=node/113965

- Escola Superior de Música, Artes e Espectáculo (ESMAE) http://www.esmae-ipp.pt/

- ECLAP http://www.eclap.eu/

- ECLAP schema http://www.eclap.eu/schema/

- MyStory Player http://www.mystoryplayer.org

- Europeana Professional http://pro.europeana.eu

- Europeana http://www.europeana.eu/

- ARROW http://www.arrow-net.eu/

- SynchronousObjects http://synchronousobjects.osu.edu

- Motion Bank http://motionbank.org/en/

- Whatever dance toolbox http://badco.hr/works/whatever-toolbox/

- iMaestro http://www.i-maestro.org

- CASPAR Project http://www.casparpreserves.eu/

- Lepecki, A. (2010) The Body as Archive: Will to Re-Enact and the Afterlives of Dances, Dance Research Journal, Volume 42, Issue 02, December 2010, pp 28-48.

http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=8512105 - Gateway to Archives of Media Art (GAMA) http://www.gama-gateway.eu/

- Transmedia Knowledge Base for Performing Arts (TKB) http://tkb.fcsh.unl.pt

- W3C OWL-2 ontology http://www.w3.org/TR/owl2-overview/

- The Space http://thespace.org

Author Details

Email: m.guy@ukoln.ac.uk

Web site: http://www.dcc.ac.uk

Marieke Guy is an Institutional Support Officer at the Digital Curation Centre. She is working with 5 HEIs to raise awareness and building capacity for institutional research data management. Marieke works for UKOLN, a research organisation that aims to inform practice and influence policy in the areas of: digital libraries, information systems, bibliographic management, and Web technologies. Marieke has worked from home since April 2008 and is the remote worker champion at UKOLN. In this role she has worked on a number of initiatives designed specifically for remote workers. She has written articles on remote working, event amplification and related technologies and maintains a blog entitled Ramblings of a Remote Worker.