eMargin: A Collaborative Textual Annotation Tool

Andrew Kehoe and Matt Gee describe their Jisc-funded eMargin collaborative textual annotation tool, showing how it has widened its focus through integration with Virtual Learning Environments.

In the Research and Development Unit for English Studies (RDUES) at Birmingham City University, our main research field is Corpus Linguistics: the compilation and analysis of large text collections in order to extract new knowledge about language. We have previously developed the WebCorp [1] suite of software tools, designed to extract language examples from the Web and to uncover frequent and changing usage patterns automatically. eMargin, with its emphasis on manual annotation and analysis, was therefore somewhat of a departure for us.

The eMargin Project came about in 2007 when we attempted to apply our automated Corpus Linguistic analysis techniques to the study of English Literature. To do this, we built collections of works by particular authors and made these available through our WebCorp software, allowing other researchers to examine, for example, how Dickens uses the word ‘woman’, how usage varies across his novels, and which other words are associated with ‘woman’ in Dickens’ works.

What we found was that, although our tools were generally well received, there was some resistance amongst literary scholars to this large-scale automated analysis of literary texts. Our top-down approach, relying on frequency counts and statistical analyses, was contrary to the traditional bottom-up approach employed in the discipline, relying on the intuition of literary scholars. In order to develop new software to meet the requirements of this new audience, we needed to gain a deeper understanding of the traditional approach and its limitations.

The Traditional Approach

A long-standing problem in the study of English Literature is that the material being studied – the literary text – is often many hundreds of pages in length, yet the teacher must encourage class discussion and focus this on particular themes and passages. Compounding the problem is the fact that, often, not all students in the class have read the text in its entirety.

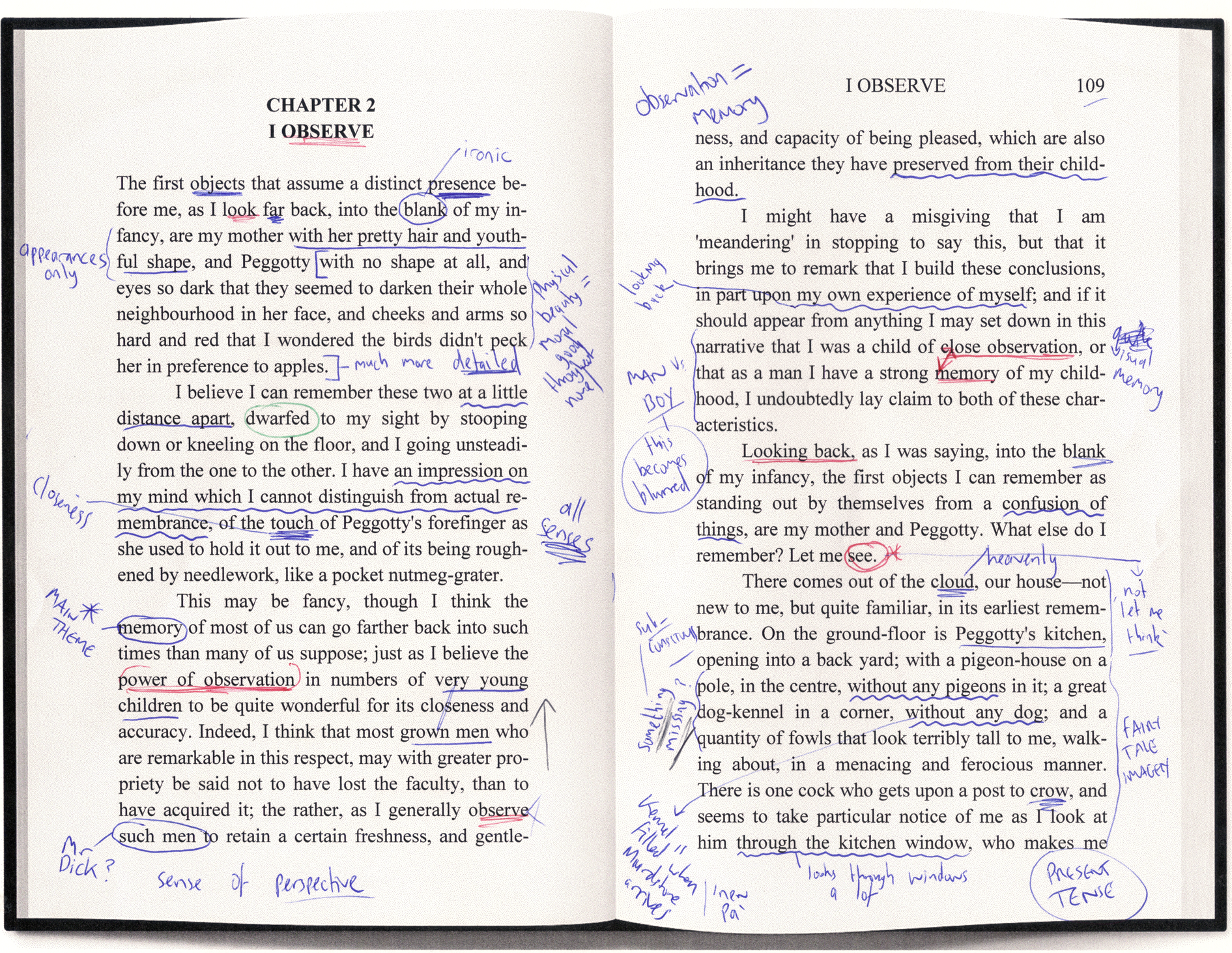

The traditional mode of study in the discipline is ‘close reading’: the detailed examination and interpretation of short text extracts down to individual word level. This variety of ‘practical criticism’ was greatly influenced by the work of I.A. Richards in the 1920s [2] but can actually be traced back to the 11th Century [3]. What this approach usually involves in practice in the modern study of English Literature is that the teacher will specify a passage for analysis, often photocopying this and distributing it to the students. Students will then read the passage several times, underlining words or phrases which seem important, writing notes in the margin, and making links between different parts of the passage, drawing out themes and motifs. On each re-reading, the students’ analysis gradually takes shape (see Figure 1). Close reading takes place either in preparation for seminars or in small groups during seminars, and the teacher will then draw together the individual analyses during a plenary session in the classroom.

Figure 1: Manual annotation of a text

Through our discussions with colleagues and students in the School of English at BCU, we discovered several limitations to the traditional approach. At individual student level, the passage of text can quickly become cluttered with underlining and notes on each successive re-reading, making it difficult to isolate particular threads of analysis or interpret the analysis at all when returning to it several weeks later (eg for revision).

Student’s annotations are very much individual and tied to their own printed copies of the text. Students cannot see each other’s annotations and teasing out and combining these private readings at class level can be a difficult task for the teacher. Moreover, comments and discussions are not captured in a form that can be archived or searched at a later date, or re-used by the teacher in subsequent years. For distance-learning students, it is even more difficult to share annotations and, in addition, these students cannot take part in discussions about the text except through online chats (which require all students to be online simultaneously) or in forums (where the text and the discussion are separate entities).

The biggest challenge facing traditional academic methods of textual analysis, however, is the continued growth of electronic texts. As the availability of e-texts has widened, many institutions have diverted increasingly scarce library budgets away from books and towards e-content platforms such as MyiLibrary [4]. In addition, there are many subject-specific databases – in our case including LION [5] and EEBO [6] – and, of course, an increasing number of e-readers like the Amazon Kindle.

Despite this proliferation of e-texts, when we began the background research for eMargin in 2007 we were rather surprised by the lack of available software to allow the kind of fine-grained annotation necessary in academic close-reading. We found many Web sites and browser plug-ins allowing electronic ‘sticky notes’ to be associated with online texts but these were usually paragraph-level annotations at best rather than the word-level annotations required in academic study. There had been attempts at more complex e-annotation tools in the past (e.g. XLibris [7]) but many of them were expensive proprietary solutions which did not find favour in the academic community. Furthermore, we were unable to find an existing tool offering the collaborative, annotation-sharing aspect required in academic group work. For these reasons, we set to work on a prototype collaborative annotation tool and began testing it in the classroom with colleagues and students.

Designing eMargin

Our initial plan was to develop a wiki-based system to allow students to collaborate on the production of a critical analysis of a literary passage. At that time, the wiki was of growing importance in scientific research in general [8] and seemed to be a useful knowledge-aggregation tool for our specific purposes. In a similar way to how Wikipedia works, students would have contributed ideas and teachers would have acted as ‘editors’, helping to shape the finished analysis.

However, when we shared our initial ideas with colleagues who teach literary studies, it soon became apparent that, while the end product – the critical analysis – is important, perhaps more important still is the discussion process involved in reaching consensus. We needed to capture this discussion process in electronic format, allowing students not only to make their own textual annotations but to respond to annotations made by their peers. A basic discussion forum would not be sufficient as, with students working in small groups or at a distance, there may be multiple discussions taking place simultaneously, associated with different parts of the literary text from paragraph level right down to single word level.

With these requirements in mind, we adopted a different approach and developed a prototype Web-based annotation system which placed the literary text itself at the centre of the interface and mirrored, as closely as possible, the process of writing notes in the margin of a printed text. In this prototype, students were able to highlight any span of text and write comments in the pop-up box which appeared on screen when they released the mouse. These comments would appear immediately on the screens of other students, who could then read their peers’ comments and respond if they wished. We decided at an early stage that our system had to be Web-based. In the academic environment, staff and students often lack the necessary permissions required to install software locally, so it was important that our tool would run in any standard Web browser.

During the prototyping stage we discovered that, independently of us, staff at the University of Leicester [9] had identified the same pedagogic issue that we outline above and had been searching, largely unsuccessfully, for pre-existing software for the collaborative annotation and discussion of literary texts. We therefore collaborated with Leicester on a pilot study, using our prototype in their English Literature classes across three modules (two BA modules, one MA module). This helped us to gauge student and teacher reactions to our prototype tool and to determine which features would be of most use in the final version. Of the Leicester students surveyed, 96% found word-level commenting useful, 92% agreed that ‘reading others’ comments helped me formulate my own ideas’, and 96% found the prototype ‘easy’ to use.

We used this feedback to support a bid to the Jisc Learning & Teaching Innovation Grant scheme. The bid was successful [10] and allowed us to develop the full-scale collaborative annotation system which became known as eMargin. The eMargin system is hosted on our server at BCU for use by other institutions [11] and is also open-source, with code available through SourceForge [12]. In the following section we outline the main features of eMargin before going on to describe how our tool is attracting new audiences in other disciplines.

eMargin Features

Basic Annotation

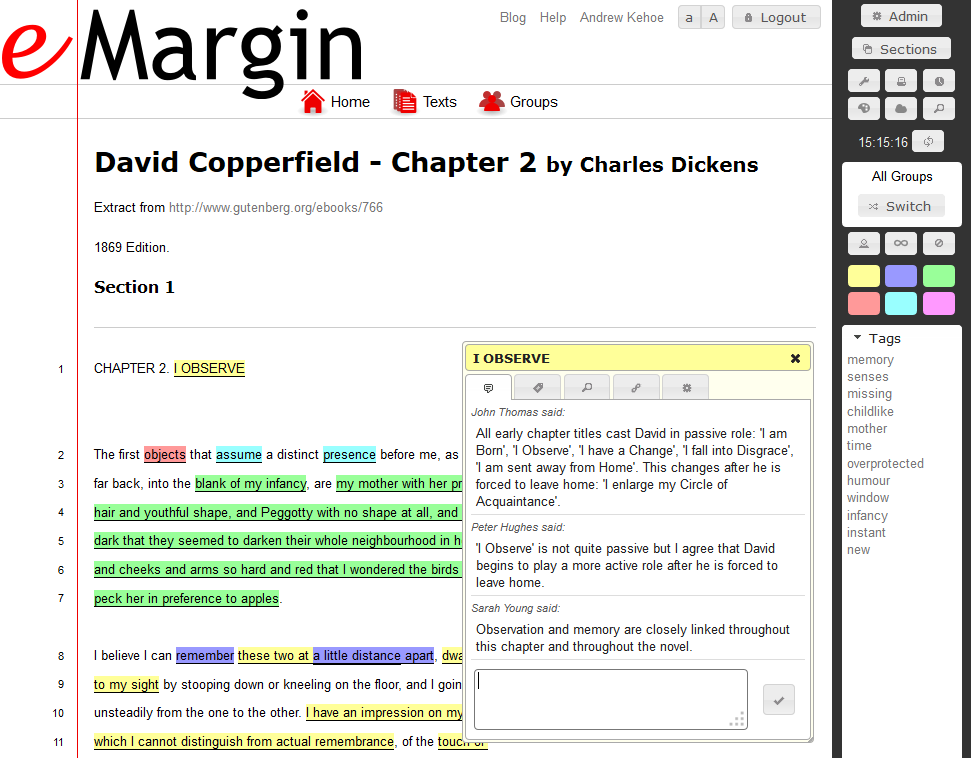

At the centre of the eMargin workspace is the text under analysis, with a toolbox on the right of the screen giving access to the main functions of the software and allowing the user to control which annotations are visible (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Main eMargin workspace

The spans of text highlighted in different colours are the annotations themselves and it is possible to open an annotation by clicking on the highlighted text. In Figure 2, an annotation has been opened which is associated with the phrase ‘I OBSERVE’ (the title of the chapter). In this case, both Peter and Sarah have responded to the original comment made by John and a discussion is developing around this particular phrase. The text box at the bottom of the annotation window allows the current user to join this discussion. The annotation window hovers over the primary text and can be dragged around the screen to wherever the user prefers. It is possible to open multiple annotation windows simultaneously and to hide them again by clicking on the small cross in the corner. This offers a significant advantage over the traditional model (Figure 1), where annotations, once made, are visible permanently.

As in the prototype, new annotations are made by dragging the mouse over the span of text to be highlighted. When the mouse button is released, the annotation window appears. We have also developed a modified version of the interface for tablets and other touch-screen devices.

It is possible, when making a new annotation, to choose the highlight colour (from the palette of six colours shown on the right of the screen). In order to make eMargin as flexible as possible, we chose to leave it to the user to determine what the individual colours mean and how they are used in the annotation process. In Figure 2 each colour is used to highlight a different theme in the novel but, depending on the specific text and analysis task, colours can be used in a variety of ways. There is an option in the toolbox to associate labels with colours to make their meaning clearer. Some of our users have employed the different colours to apply several different analytical models to a text whereas some groups of users have assigned a different colour to each group member’s annotations.

By clicking on a colour in the palette in the toolbox, it is possible to view only the annotations of that colour and this is a useful way of filtering the overall analysis in to threads or themes. It is also possible for users to view only their own annotations or annotations made by members of their own group (see Group Management section below).

Tagging

In recent years, there has been an explosion in the activity of ‘tagging’: the association of single word descriptors with online resources, from videos and photographs to news articles, academic papers and items for sale in online stores. eMargin takes this a step further and allows tags to be associated with sub-sections of a text, down to individual word level. The most frequently assigned tags are listed in the toolbox and it is also possible to view a tag cloud showing the most frequent tags in the largest typeface. By clicking on an individual tag, either in the list or in the tag cloud, the user can view sub-sections of the text which have been associated with that tag. There are therefore two different kinds of association available in eMargin: colour association and word association. The user can choose to use one or the other or to combine them in whatever way is appropriate for the annotation task in hand.

Tags were also a way of introducing into eMargin the quantitative aspect of our previous work in the field of Corpus Linguistics. The eMargin tagging tool gives users a basic way of carrying out a qualitative, intuition-based textual analysis but then counting which of the identified features are most frequent and, thus, perhaps most significant.

Text Upload

In any annotation tool, the user must be able to insert texts for analysis and in eMargin this is achieved in one of three ways. The user can upload a text from his or her computer, with PDF, Word, HTML and many other text-based formats supported. Alternatively, the user can specify the URL of an online document to be downloaded. The third option is a simple copy and paste mechanism. If one of the first two options is chosen, eMargin processes the document and converts it to plain text and allows the user to edit this text before making it available for analysis in the main interface. At present, eMargin does not preserve document layout or other formatting. Whilst this is not usually significant in literary studies or other kinds of academic analysis, we are investigating ways of preserving document formatting in a future version of our software.

Group Management

There are three main entities within eMargin: user, text, and group. All registered users have permission to upload texts, in the manner described above, and to make their own private annotations. One of the key advantages of eMargin, however, is in allowing users to share and discuss their annotations. This is achieved through the groups mechanism. Users who have been given enhanced permissions (teachers in the academic environment) are able to create a group and share texts with this group. Other users can be given access to the group and associated texts through the use of ‘special access links’. A special access link is a secret URL, which can be generated within eMargin and then shared with other people (eg by email). Anyone clicking on the special link is given access to the group, after signing up for eMargin if (s)he does not already have an account. The owner of the group can choose whether other users are given read-only access, standard access or moderator access (permission to delete annotations made by other users).

Look-up

eMargin offers integration with external resources through its ‘look-up’ feature. When selecting a span of text, the user is given the option to search for the corresponding word, phrase or sentence in the online edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, in Google, in Wikipedia or in our own WebCorp tool, amongst various other online search tools and repositories. eMargin generates an appropriate search string automatically and takes the user directly to matches for the search term selected from the text under analysis. The most obvious use for this feature is in looking up the definition of unknown terms but there is potential for closer integration with further repositories.

Search and Retrieval

There is a search facility in the eMargin toolbox which allows users to search for words or phrases within a highlighted span of text or within the annotation and comments associated with a highlight. Searches can be restricted by highlight colour, tag, user, group or date. Within eMargin, all actions are logged and time-stamped so it is possible to determine exactly who contributed what and when. This is particularly useful in the academic environment when groups of students are collaborating on an analysis. It is also possible to create permalinks to individual annotations to aid retrieval.

Output Formats

eMargin is designed primarily as an online workspace. However, there are situations where an annotated text may be required in printed form or in machine-readable form for use by other software tools. In the first case, eMargin offers a printable version, of the annotations only or of the annotations shown as endnotes within the full text (with colour-coding preserved). In the second case, eMargin offers an XML output option which allows the user to export the text and/or annotations and tags in TEI-compliant XML.

eMargin Technical Details

eMargin was implemented in Java, including JSP for the Web interface, and JavaScript, including jQuery and jQuery UI [13]. After exploring the available options, we decided that interactions with the database would be handled using the Java Persistence API (using Hibernate as the implementation and H2 as the relational database system). Further technical specifications are available on the Jisc CETIS Web site [14].

In general, eMargin is a fairly standard Web application, made up of server- and client-side scripting. The more complex element of the tool is the user interface for adding and viewing annotations. We made use of AJAX requests to create a dynamic interface, and we found jQuery (specifically its UI sub-project) extremely useful in allowing us to focus on functionality without having to worry about building display elements.

During development of the prototype annotation interface, there was one major challenge that needed to be overcome. Initially, our plan was for annotation to be allowed at character level, and development started along these lines. This required the exact position in the text of a new highlight to be determined using the Web browser’s own built-in text selection mechanism. However, we soon realised that the number of characters displayed on screen can differ from the number of characters in the HTML source and that this can vary between Web browsers. We tried various strategies to combat this problem. In the prototype we settled for marking the position of each annotation with specific HTML tags and then counting the characters in the source up to that position. Deciding that this solution was too inefficient, we changed the minimum annotation level from character to word in the full eMargin tool.

Dividing a text into words (tokenisation) is something we have much experience of from our work in Corpus Linguistics. Using our own tokenisation rules, we were able to split the text in eMargin into words and surround each word with HTML tags, clearly defining its boundaries. This enabled us to write our own text selection system to ensure accuracy and improve performance. A useful by-product of this was that we could adapt our selection system for touch-screen devices relatively easily. This resulted in three methods for text selection: dragging a mouse, dragging a finger on a touch-screen device, or using a sequence of taps and a pop-up menu (for devices with limited touch support).

Widening Our Audience

As explained above, our Jisc Learning & Teaching Innovation project had the study of English Literature as its primary focus. What may have become apparent in this article so far, however, is that eMargin includes features of use in any discipline or situation where close textual analysis is important, particularly where it is carried out collaboratively. From the early stages, eMargin attracted interest across subject areas at our own institution from Health to Law, and from Education to Fine Art. As Rowin Young of Jisc CETIS wrote of eMargin in an October 2011 blog post ‘[b]y providing an easy means for sharing ideas […] this system will be of value in all disciplines, not just English Literature where it is being developed’ [15].

To give an example of the wider use of eMargin, a research team at Lancaster University working on the ESRC-funded Metaphor in end-of-life care (MELC) Project [16] is using eMargin to investigate the role metaphor may play in the discussion of illness and death. The project has involved collaboration between three analysts on the manual annotation of metaphors in transcripts of interviews conducted with a variety of stakeholders, including patients, unpaid family carers, and healthcare professionals. eMargin has allowed analysts to view one another’s annotations, make comments and reach majority decisions on tricky cases. The XML-export option has also proved useful in passing the annotations to specialist software for further statistical analyses. The findings of the MELC project will be relevant to the provision of end-of-life care, and to the training of healthcare professionals.

The continued growth of e-texts has meant that the need for effective digital annotation has extended beyond academia and become a mainstream issue. A 2011 New York Times article entitled ‘Book Lovers Fear Dim Future for Notes in the Margins’ [17] traced the history of reader annotation and spoke of its ‘uncertain fate in a digitalized world’. eMargin was discussed at the NISO meeting on Standards Development for E-Book Annotation Sharing and Social Reading at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2011 [18] and in 2012 we were invited to the British Library to speak in the ‘Digital Conversations’ series about the wider applicability of our tool.

In recent years there has been a growing recognition that user-generated content like the annotations found in eMargin has great potential as a means of improving the accessibility and overall value of digital library collections [19]. We feel that user-assigned tags could be particularly useful in overcoming the limitations of traditional expert-driven taxonomic classification systems when applied to Web-scale text collections. In a previous study [20] we analysed the potential of such tags as a source of document metadata and found that, with appropriate linguistic insight, tags could be used to improve library and Web indexing by offering an indication of textual topic. The increased benefits offered by eMargin’s sub-document-level tags (paragraph, sentence, phrase, word) are something we plan to explore in future work.

Integration with Virtual Learning Environments

In spite of the growth and diversification of the eMargin user-base during the course of its development, a point frequently made by teachers using the tool was that the need to register separately for eMargin acted as a barrier to use. With the growth of single sign-on for university Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs), intranet sites and library systems, students increasingly expect a seamless experience when using electronic resources, and we found in our trials that the introduction of a separate registration system sometimes led to a sense of disorientation. For teachers, there was the problem of ensuring that all students in the class had registered to use the external tool. Where students registered for eMargin using only a personal email address, there was an additional difficulty for the teacher and the system administrator in associating users with courses, groups and, in the case of our own hosted eMargin service, institutions.

For these reasons, we felt that there was a clear case for tighter integration between eMargin and the VLE, and that such integration would encourage wider uptake of our system. To achieve this, we made use of the Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI) specification published by the IMS Global Learning Consortium [21]. LTI is a seamless way of integrating external resources with VLEs, and one that is compatible with all the major VLE systems including Moodle and Blackboard Learn.

In our case, the main benefit of LTI was in streamlining the user registration and log-in process. We were able to secure funds from the Jisc Embedding Benefits programme [22] to produce an enhanced version of eMargin with LTI integration. What this means is that users of any supported VLE (or other LTI-compatible software) can click on a link and have their credentials – institution, course, role, name, email address – passed securely to eMargin, removing the need to log in to eMargin separately. It is, of course, still possible to log in using the previous method if required.

Conclusion

In this article we have explained how, by gaining an insight into the pedagogical and technological challenges being faced in the close study of academic texts, we have been able to develop an effective online collaborative annotation system. We have shown that, by making this system as flexible and user-friendly as possible and by integrating it with institutional VLEs, we have attracted users beyond our initial target audience. In doing so, we have developed expertise and software resources which we hope will be reused by other developers working on a variety of annotation tasks.

References

- WebCorp: The Web as Corpus http://www.webcorp.org.uk/

- I.A. Richards (1929) Practical Criticism. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner

- Brian Cummings (2002) The Literary Culture of the Reformation. Oxford: OUP.

- MyiLibrary http://www.myilibrary.com/

- Literature Online http://lion.chadwyck.com/

- Early English Books Online http://eebo.chadwyck.com/

- Morgan N. Price, Bill N. Schilit & Gene Golovchinsky (1998) ‘XLibris: The Active Reading Machine’. Proceedings of CHI '98: Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York: ACM. pp. 22-23

http://www.fxpal.com/publications/FXPAL-PR-98-111.pdf - Mitch Waldrop, ‘Big data: Wikiomics’. Nature Vol. 455, Issue 7209, 4 September 2008. pp. 22-25 http://www.nature.com/news/2008/080903/full/455022a.html

- Colleagues at Leicester were then in the early stages of their #tagginganna Project

https://sites.google.com/site/tagginganna/ - eMargin – an online collaborative textual annotation resource

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/elearning/ltig/emargin.aspx - eMargin http://emargin.bcu.ac.uk/

- eMargin | Free software downloads at SourceForge.net http://sourceforge.net/projects/emargin/

- jQuery http://jquery.com/

- Project Directory http://prod.cetis.ac.uk/projects/emargin

- Under development: eMargin << Rowin's Blog

http://blogs.cetis.ac.uk/rowin/2011/10/10/under-development-emargin/ - Metaphor in end-of-life care (MELC) Project http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/melc/

- Dirk Johnson. Book Lovers Fear Dim Future for Notes in the Margins, New York Times, 20 February 2011

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/21/books/21margin.html - E-Book Annotation Sharing and Social Reading - National Information Standards Organization

http://www.niso.org/topics/ccm/e-book_annotation/ - Rich Gazan (2008) ‘Social Annotations in Digital Library Collections’. D-Lib Magazine. Vol. 14, Number 11/12 http://www.dlib.org/dlib/november08/gazan/11gazan.html

- Andrew Kehoe & Matt Gee (2011). ‘Social Tagging: A new perspective on textual “aboutness”. Studies in Variation, Contacts and Change in English, Vol. 6

http://www.helsinki.fi/varieng/journal/volumes/06/kehoe_gee - IMS Global: Learning Tools Interoperability http://www.imsglobal.org/toolsinteroperability2.cfm

- eMargin – embedding a text annotation tool in VLEs

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/elearning/embeddingbenefits2012/eMarginembedding.aspx

Author Details

Email: andrew.kehoe@bcu.ac.uk

Web site: http://www.bcu.ac.uk/pme/school-of-english/staff/andrew-kehoe

Andrew Kehoe is Director of RDUES and Deputy Head of the School of English at Birmingham City University. Since 1999 he has worked on a series of EPSRC- and AHRC-funded projects in the field of Corpus Linguistics, most recently managing the Jisc-funded eMargin Project.

Matt Gee is the developer behind eMargin and various other software tools and data collections released by RDUES, including the WebCorp Linguist’s Search Engine and Birmingham Blog Corpus.