LinkedUp: Linking Open Data for Education

Marieke Guy, Mathieu d’Aquin, Stefan Dietze, Hendrik Drachsler, Eelco Herder and Elisabetta Parodi describe the activities carried out by the LinkedUp Project looking at the promotion of open data in education.

In the past, discussions around Open Education have tended to focus on content and primarily Open Educational Resources (OER), freely accessible, openly licensed resources that are used for teaching, learning, assessment and research purposes. However Open Education is a complex beast made up of many aspects, of which the opening up of data is one important element.

When one mentions open data in education a multitude of questions arise: from the technical (what is open data? What is linked data? How do I create open datasets?), the semantic (what is the difference between Open Education data and open data in education?) to the more philosophical (what exactly is Open Education anyway? How can we make sure ‘open’ means ‘accessible to all’? How can opening up data be helpful?) All valid questions, yet not all with straight-forward answers; however exploration around what might purport to be answers to these questions is very much in scope for the LinkedUp Project.

The LinkedUp Project (Linking Web data for education) [1] is an EU FP7 Coordination and Support Action running from November 2012 to November 2014 which looks at issues around open data in education, with the aim of pushing forward the exploitation of the vast amounts of public, open data available on the Web. It aspires to do this by facilitating developer competitions and deploying an evaluation framework, which identifies innovative success stories of robust, Web-scale information management applications. The project comprises six pan-European consortium partners [2] led by the L3S Research Center of the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover and consisting of the Open University UK, the Open Knowledge Foundation, Elsevier, the Open Universiteit Nederland and eXact learning LCMS. The project also has a number of associated partners [3] with an interest in the project including the Commonwealth of Learning, Canada and the Department of Informatics, PUC-Rio, Brazil.

Figure 1: The LinkedUp Web site

Open and Linked Web Data

The LinkedUp Project focuses on open Web data and has its roots in the linked data movement. The project recognises that while World Wide Web began as a global space in which to link primarily documents, through the development of Web standards and the inclusion of semantic content in Web pages there is now an increasing need for access to raw data that sit separately from documents. Publishing these data in a structured way as linked data, through the use of URIs and RDF, provides an opportunity for these data to become much more useful.

As Tim Berners-Lee explains:

‘The Semantic Web isn't just about putting data on the web. It is about making links, so that a person or machine can explore the web of data. With linked data, when you have some of it, you can find other, related, data.’ [4]

The Semantic Web is an overarching concept, a common framework that allows data to be shared and reused across applications, and Linked data is one part of this framework. Many use the terms semantic web synonymously with linked data. For a lay-person the easiest way to understand both the Semantic Web and linked data is through the idea of a ‘web of data’. So for example if you searched for lecturers at an institution you could find their name, but you could also find all the papers that they have written, where those papers were published, definitions of all the topics they cover, details of all the other universities involved, and so on. Searching is considerably enhanced by semantics: you would know that the author with the very commonplace name John Smith you searched for was the lecturer at ‘University A’ rather than the one at ‘University B’ because all key elements have unique identifiers. The result is a much more intelligent system than the current Web. There are many better concrete examples out there, the Ordnance Survey linked data video [5] offers a good introduction.

So are people already creating linked data? The book: Linked Data: Evolving the Web into a Global Data Space [6] reports that there are 50 billion facts published as linked data on the Web today, while the W3C notes that in September 2011 there were a billion RDF triples, interlinked by around 504 million RDF links [7]. These data cover most academic domains, cross-domain datasets (such as DBpedia, a crowd-sourced community initiative to extract structured information from Wikipedia [8]) and governmental data [9]. In addition to the more technology-centric publication of data, many initiatives have emerged recently that follow the more general principle of open data, from governments and public institutions to local and private institutions (eg the Guardian data blog [10]).

Linked data must adhere to the four principles of linked data outlined by Tim Berners-Lee in his Design Issues Linked Data note [11]. They could be summarised as:

- use URIs to denote things;

- use HTTP URIs so that these things can be referred to and looked up;

- provide useful information about the thing when its URI is dereferenced;

- leverage standards such as RDF, SPARQL and;

- include links to other related things (using their URIs).

But when they are published on the Web, open data do not necessarily have to be structured, but they have to be open. The Open Definition [12], developed by the Open Knowledge Foundation [13], sets out principles that define ‘openness’ in relation to data and content. It can be summed up in the statement that: ‘A piece of data or content is open if anyone is free to use, reuse, and redistribute it — subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and/or share-alike.’ The LinkedUp Project advocates use and creation of linked data and recognises the value of open data.

Open and Linked Data in UK Higher Education

In the education sector, the benefits of using open and linked Web data are starting to show with several universities engaged in the deployment of linked data approaches. In the UK this has been driven by a requirement for transparency and accountability in public institutions, directed by government. However there is also a relatively recent acknowledgement that sharing data not only allows comparison between individual institutions and cluster groups but can also inform decision-making. The creation of innovative tools, as supported through LinkedUp activities, can bring together different datasets and offer new perspectives. These new perspectives are nicely illustrated in a UK project on sharing equipment data. The UK University Facilities and Equipment Open Data project [14] was funded by a UK research council in response to a need to facilitate discussions around equipment sharing among UK universities. It delivers a national ‘shop window’ for research equipment and supports searching across UK HE equipment datasets. The service forms part of the data.ac.uk initiative formed by the community of UK university open data projects. One institution that has been doing some really interesting work in this area is the University of Southampton [15]. Staff there have created an open data service and brought together datasets on many aspects of university life such as locations, course details, people and travel information. The result is many interesting views on the data that allows you, for example, to find out what coffee shops are open on campus, what they sell and how to locate them. Or what courses are on at what time and whether students rate them highly. Another interesting project in this area is mEducator [16] which provides linked data on open educational resources and has led to community platforms such as LinkedEducation.org [17], an open platform which promotes the use of linked data for educational purposes. One of the project’s aims is to identify best practice and potential links between individual resources in order to contribute to a well-connected educational Web of Data.

For those involved in the LinkedUp Project it is clear that the availability of open teaching and education-related data represents an unprecedented resource for students and teachers. It has the potential to introduce a paradigm shift in the way educational services are provided, substantially improve educational processes and lower the costs of providing Higher Education. Nonetheless, so far, the potential of using educational Web data has been vastly underexploited by the educational sector. Applications and services often only make use of very limited amounts of data and distributed datasets; nor do they provide users with an appropriate level of context and filtering for the vast amounts of heterogeneous content retrieved to make it possible for such information to be adequately exploited. The LinkedUp Project hopes to engage with communities working in this area, and also with others who have yet to see the potential of open and linked data for educational purposes. Its aim is to encourage more activity in the open and linked data arena, in particular by educational institutions and organisations.

The LinkedUp Challenge

One of the principal ways it intends to encourage engagement is through a series of open competitions designed to elicit Web data-driven applications for personalised, open and online university-level studies. The LinkedUp Challenge [18] is a series of three consecutive competitions which seek interesting and innovative tools and applications that analyse and/or integrate open Web data for educational purposes. The competitions are open to anyone, from researchers and students, to developers and businesses. The second and third competitions will build upon their predecessor; leading from innovative prototypes and tools through to large-scale deployable systems. Participants are required to solve critical issues with respect to Web-scale data and information discovery and retrieval, interoperability and matchmaking, data quality assurance and performance. The challenge builds on a strong alliance of institutions with expertise in areas such as open Web data management, data integration and Web-based education.

The first competition (Veni) ran from to 22 May to 27 June 2013. Extensive promotion was carried out using Twitter, blog posts and pan-European mailing lists. By the closing date 22 valid submissions had been received from 12 different countries (four from the UK, three from France, three from Spain, three from the USA, 2 from the Netherlands and 1 each from Argentina, Belgium, Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, and Nepal). The abstracts are available from the LinkedUp Challenge Web site [19]. The majority of entries were from teams based at universities or from start-up companies, but there were also a few from independent consultants. Some entries were developed by large teams, for example one had 9 people listed as authors and others had authors spread across different countries and organisations, while other entries had sole authors.

Entries and Judging

The entrants to the competition had interpreted the specification ‘educational purposes’ in a variety of innovative ways. A number of the entries had looked at Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and course data and offered cross-searching mechanisms while others had concentrated on discipline-specific data and offered new pedagogical approaches for learners to explore and understand subjects. Two of the submissions focused on cultural heritage data and how museum data could be used in an educational context. The remaining submissions covered other educationally related areas including use of conference publications, reading lists, mobile learning and annotation.

The submissions were judged using two different approaches. An evaluation framework was used to assess entries and the wider public were also given the opportunity to vote on entries in the People’s Choice. The People’s Choice was operated using Ideascale [20], a cloud-based crowdsourcing service combined with poster voting at the Open Knowledge (OKCon) festival in Geneva [21]. The online voting approaches adopted in the People’s Choice are explained in a blog post on the Remote Worker blog [22]. After entries were reviewed by the evaluation committee, led by the LinkedUp advisory board, a shortlist of eight was agreed on 16 August 2013. The shortlist consisted of:

- Knownodes is a collaborative Web site that supports relating, defining and exploring connections between Web resources and ideas, making use of graph visualisations. Knownodes scored high on educational innovation.

- Mismuseos connects museum data with sources including Europeana, Dbpedia and Geonames. With Mismuseos, learners can browse and explore the backgrounds and relations between objects from multiple Spanish museums.

- ReCredible is a browsable topic map with Wikipedia-like content alongside. The topic library showcases interesting topics varying from dog breeds and alternative medicine to nanotechnology and information systems.

- DataConf is a mobile mashup that enriches conference publications. The reviewers applauded its attractive and effective design. DataConf is especially useful at the graduate education level.

- We-Share is a social annotation application for educational ICT tools. We-Share can help educators to find tools to support teaching at all educational levels, and received high scores on educational innovation.

- YourHistory is a Facebook app that makes history tangible by showing historic and global events that are related to your own life events and your interests.

- Globe-Town is a ‘fun-to-use’ tool that enables users to find out the most important trade partners, migrant populations and airline routes in their own countries. It also provides infographics on issues regarding society, environment and economy.

- Polimedia connects transcripts of the Dutch parliament with media coverage in newspapers and radio bulletins. Polimedia employs innovative information techniques and provides an attractive front-end that invites exploration and browsing.

The shortlisted entrants were invited to the Open Knowledge Conference (OKCon) [21] in Geneva to take part in the LinkedUp Award Ceremony where first, second, and third prizes were awarded. The third place was awarded to We-Share, the second place was awarded to Globe-Town and the first place was awarded to Polimedia. The People’s Choice was awarded to We-Share. Further details of the awards ceremony are available from the LinkedUp blog [23].

Figure 2: The Veni Competition shortlist entrants receive their awards

The next competition, the Vidi competition, was launched by LinkedUp in early November 2013 and will run until 14 February 2014.

Evaluation Framework

As mentioned earlier, the LinkedUp Challenge is being assessed using a well-defined evaluation framework. During initial stages of the project, the project team carried out a thorough assessment of the technical landscape in the field of open (educational) Web data (eg linked data, data mining, learning analytics, legal and privacy aspects). This information was fed into the initial design of the LinkedUp Challenge and helped to provide a detailed description of the requirements which had to be met by entrants. It is intended that these requirements will ensure the large-scale reusability and exploitation of the challenge results and positive impact on the educational sector within Europe.

The evaluation framework consists of predefined evaluation procedures and benchmarking criteria for the ranking of the participating projects during the LinkedUp competitions. The requirements include interdisciplinary coverage, integration of high-quality Web data, integration with local data, context and filtering, scalability and performance and multilingualism. The evaluation framework consists of a transparent and distinct list of evaluation criteria that enable the review panel to measure, based on quantifiable criteria and qualitative assessment, the impact and appropriateness of large-scale Web information and data applications. The evaluation framework also helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of individual projects and submissions. These ratings are being used by LinkedUp to analyse ‘gaps in knowledge’ and offer customised technology transfer workshops to support the participating projects and guarantee an effective knowledge exchange during the LinkedUp challenge. After each stage of the Challenge, the evaluation framework is being reviewed on its validity and as to possible improvements that could be made to achieve the most sustainable and practical evaluation instrument possible by the end of the project. It is envisaged that the LinkedUp evaluation framework will contribute to an overall evaluation framework for knowledge- and data-intensive applications in particular domains (such as education).

In order to implement the evaluation framework, an evaluation experts group has been established, composed of experts from within and outside the LinkedUp Project (consortium, associated experts, external experts). The evaluation panel began by analysing the evaluation framework itself (evaluation criteria, benchmarks and methods) to guarantee the reliability and validity of the selected measures and participated in the evaluation of the LinkedUp Challenge submissions.

Use Cases

One interesting area of work in the LinkedUp Project is the development of large-scale scenarios and use cases for the deployment, evaluation and exploitation of the challenge submissions/applications. These use cases will provide the basis for the evaluation of the LinkedUp Challenge submissions in real-world scenarios involving a critical mass of users as well as data, where submitted applications will be deployed and evaluated according to the evaluation criteria defined in the challenge design. Four use cases were defined for the Veni competition:

- Teaching going social;

- Educationizer;

- Simplify; and

- Supporting employees’ development via didactic guidance through learning materials [24].

These were large-scale scenarios and use cases that arose through consultation among LinkedUp Project members and associated partners. For example:

- ‘How can teachers in the developing world benefit from the open resources freely available online?’

- ‘How do you make research more accessible and understandable for people without an academic degree?’

- ‘How can teachers put courses together benefiting from online resources from Massive Open Online Courses, social media, etc?’

The use cases present actual, real-life challenges that the related institutions are facing and addressing. Their aim is to provide challenge participants with inspiration and examples of the kinds of problems that submissions can address.

For the second competition, Vidi, the LinkedUp team has developed slightly different use cases. Particular institutions are coming up with ‘focused tasks’ that would resolve a particular difficulty they are confronting . It is envisioned that solving problems for institutions, such as the BBC, will encourage participation and offer real kudos to participants.

The team looking at use cases is also preparing and implementing an exit and sustainability strategy for the long-term exploitation of the project results. This approach hopes to ensure the persistence and long-term availability of the competition results and evaluation framework produced in LinkedUp. The exit and sustainability strategy will in particular also cover legal and privacy aspects which are of importance when exposing and using publicly available Web data. The strategy will define appropriate licensing schemes and the setup of joint consortia/entities to handle future business opportunities related to LinkedUp outcomes.

Data Catalogue

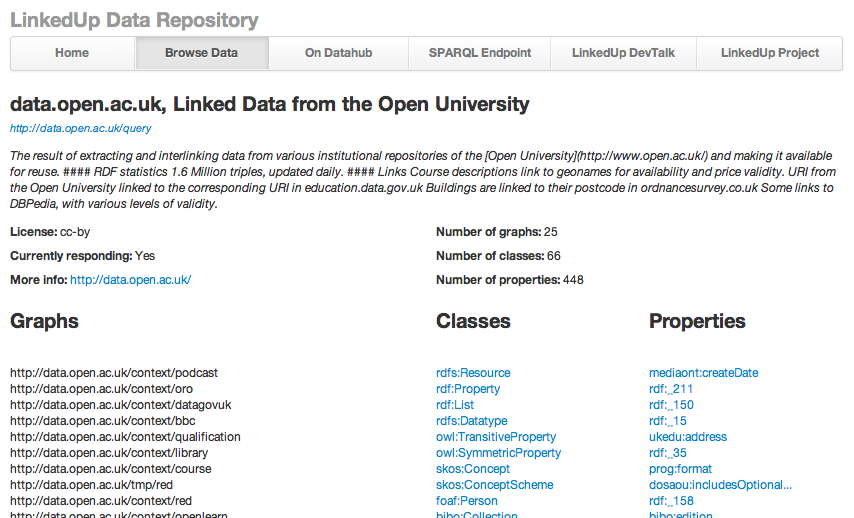

In order to support the LinkedUp Challenge and to aid use of open and linked data in education more generally, the project is continuously selecting and cataloguing relevant datasets. This has been done through the creation and maintenance of a catalogue and repository of data relevant and useful to education scenarios. The goal of the LinkedUp Dataset Catalog (or Linked Education Cloud) [25] is to collect and make available, ideally in an easily usable form, all sorts of data sources of relevance to education. The aim is not only to support participants of the LinkedUp Challenge in identifying and conjointly using Web data in their applications, but also to be a general, evolving resource for the community interested in Web data for education. During the project lifespan the technical team will enable and encourage content- and data-providers to contribute new material to the LinkedUp Dataset Catalog through a series of hands-on workshops and the promotion of community documentation on LinkedUp tools, workflows and lessons learned.

Figure 3: Open University data in the LinkedUp catalogue

The LinkedUp Dataset Catalog can be used in many ways. It is first and foremost a registry of datasets, Datahub.io [26] is probably the most popular registry of global catalogues of datasets and forms the heart of the Linked Open Data cloud. In the interest of integrating with other ongoing open data effort, rather than developing in isolation, the LinkedUp Dataset Catalog has been created as part of Datahub.io. It takes the form of a community group in which any dataset can be included. Any dataset in Datahub.io can be included in the Linked Education Cloud group (provided it is relevant), and the datasets in this group are also visible globally on the Datahub.io portal. Every dataset is described with a set of basic metadata and assigned resources. This makes it possible to search for datasets and employ faceted browsing of the results both globally or specifically in the Linked Education Cloud. For example, one could search for the word ‘university’ in the Linked Education Cloud, and obtain datasets that explicitly mention ‘university’ in their metadata. These results can be further reduced with filters, for example to include only the ones that provide an example resource in the RDF/XML format.

Alongside the data catalogue, the more technical members of the LinkedUp team have been involved in virtual development and will be organising ‘code clinics’ during the last two stages of the LinkedUp Challenge to ensure that the development and deployment of participant’s applications are not hampered by technical problems. Support is not just technical but also more general regarding legal, exploitation and dissemination issues related to participants’ applications. These processes will ensure that by the end of the project the results of the challenge can be taken up by educational organisations, commercial organisations or the development community with a clear legal and exploitation framework for each application. Discussions around the technical framework of the LinkedUp Project are carried out on the Devtalk blog [27].

Open Education Network

The LinkedUp Project has a defined lifespan and concludes in November 2014. It is anticipated that the legacy of the project will be carried on through the creation of a sustainable network. One aim of the competitions is to promote an active, diverse and well-connected community of content producers, metadata experts, technologists and others in academia, data management communities, publishing and beyond, both by strengthening existing networks and engaging new stakeholders. Much of the initial activities include dissemination of LinkedUp results (evaluation framework, datasets, LinkedUp challenge submissions) and relevant outcomes to a wider community and the transfer of innovative results and knowledge from academic and research contexts into industrial and application scenarios. LinkedUp has presented at events including Extended Semantic Web Conference (ESWC) 2013, Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK) 2013 and the International World Wide Web Conference, 13-17 May 2013 held in Rio de Janiero, Brazil [28].

Figure 4: Open Education Working Group logo

One core activity of the project is to establish a network of open Web data and resource evangelists (in particular in the area of education) who will raise awareness of legal and technical best practice in a variety of domains, facilitate conversation and collaboration between technologists in the Open Educational resource community and engage end-users in teaching and learning. The Open Knowledge Foundation in particular is keen to see the discussions around open data in education pulled into the wider debates on Open Education. This is happening through the establishment of an Open Education Working Group [29]. The Open Knowledge Foundation defines the working groups it hosts as collaborations of individuals, who meet virtually and in person to focus on a particular area of open knowledge and its effect on society. Another important aspect of working groups is the opportunity for cross-organisation collaboration through engagement with pre-existing groups. The Open Education Working Group will have a broad remit but intends to work closely with other groups already active in this area, such as the OER community and the W3C Open Linked Education Community Group [30]. It will cover all aspects of Open Education, from Open Educational Resources (OER) and changing teaching practices, to areas such as opening up relevant educational data and changing both institutional and wider culture. It hopes to be able to link with existing networks and bring groups together. It intends to look at the synergies between activities, projects and people acting in Open Education.

Figure 5: Open Education Panel Session at OKCon. From left to right:

Mathieu d’Aquin, Davide Storti, Jackie Carter and Doug Belshaw

The Open Education Working Group was launched at OKCon [21] at a panel session on Open Education [31] facilitated by Doug Belshaw from Mozilla. The panelists were Jackie Carter, Senior Manager, MIMAS, Centre of Excellence, University of Manchester, Davide Storti, Programme Specialist, Communication and Information Sector (CI), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and Mathieu d’Aquin, Research Fellow, Knowledge Media Institute, Open University, UK. The panel session was entitled: The facets of Open Education: resources, data and culture. It considered questions such as: What is Open Education? What role can open data play to make education better, more accessible and more open? How can we ensure that Open Education really widens participation? How can we encourage MOOC developers to open up their data?

In the forthcoming months the working group will develop its governance structure by adding an advisory board, an ensemble of experts in the Open Education field, and increasing its member numbers through the Open Education mailing list. Initially the group will be co-ordinated by members of the LinkedUp team but it is anticipated that in the future this role will be passed on to someone active in the community who can ensure that the group remains active and relevant.

One of the first activities of the working group will be the creation of an Open Education Handbook, a collaboratively written living Web document targeting educational practitioners and the education community at large, which will contain a significant section on open data in education. It will be a resource for both educators and Web data providers as well as adopters. The Open Education Handbook was initiated at a booksprint held in central London [32] on 3 September 2013 and Open Education experts from many different sectors (commercial, academic, government, not-for-profit) were invited to attend. The booksprint methodology (initiated by Adam Hyde of booksprints.net [33]) involves moving from zero to a published book in three to five days. It was decided to take a less-pressurised and more collaborative approach to writing the Open Education Handbook. While the handbook process has begun with a mini-one-day-booksprint to get the initial outline of the handbook, the final edited version will be written collaboratively over a longer time period of time (with a final version delivered in October 2014). The mini-booksprint saw 17 Open Education experts come together to participate in brainstorming and discussion and write over 30 pages of outline and written text.

Figure 6: Images from the Open Education Handbook booksprint

Other areas of interest for the Open Education Working Group include moving forward the debate on opening up MOOC data, building up evidence and case studies around open data use in education and collaborative activity building lists of resources and best practice.

Conclusions

Open Education is a broad area of work, and activity spans sectors and continents. While the LinkedUp Project is primarily interested in the use of open Web data in education, it also acknowledges the need to build a community whose interests go beyond the technical aspects of data creation and use. Ultimately Open Education is about eliminating barriers and supporting learning, and open data can be a support to both. However open data must be accurate, valid, timely, usable and complete before it becomes useful. It must also be hugely relevant to its audience and interpreted in appropriate ways. The LinkedUp Project recognises this and accepts that while technology is an aide, open data is really about people

References

- LinkedUp Project Web site http://linkedup-project.eu

- LinkedUp Project consortium partners http://linkedup-project.eu/about/consortium-partners/

- LinkedUp Project associated partners http://linkedup-project.eu/about/associated-partners/

- Tim Berners-Lee, Design Issues Linked Data Note, 27 July 2006

http://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/LinkedData.html - Ordnance Survey linked data introductory video

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qBEkW1wmEM&feature=player_embedded - Heath, T. and Bizer, C. (2011) Linked Data: Evolving the Web into a Global Data Space (1st edition). Synthesis Lectures on the Semantic Web: Theory and Technology, 1:1, 1-136. Morgan & Claypool.

- W3C SweoIG/TaskForces/CommunityProjects/LinkingOpenData

http://www.w3.org/wiki/SweoIG/TaskForces/CommunityProjects/LinkingOpenData - DBpedia http://dbpedia.org/

- In the UK we have Data.gov http://data.gov.uk and http://data.legislation.gov.uk

- Guardian data blog http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog

- Tim Berners-Lee, Design Issues: Linked Data note, June 2006

http://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/LinkedData.html - Open Definition http://opendefinition.org

- Open Knowledge Foundation http://okfn.org

- University Facilities and Equipment Open Data Project: Enabling access to UK HE research equipment http://equipment.data.ac.uk/

- University of Southampton Open Data Service http://data.southampton.ac.uk

- mEducator http://linkededucation.org/meducator

- Linkededucation.org http://linkededucation.wordpress.com

- LinkedUp Challenge http://linkedup-challenge.org

- LinkedUp Challenge: Veni Submissions http://linkedup-challenge.org/veni.html

- LinkedUp Ideascale site http://linkedup.ideascale.com

- OKCon http://okcon.org

- Online Voting: The highs and lows, Ramblings of a Remote Worker blog, 9 August 2013 http://remoteworker.wordpress.com/2013/08/09/online-voting-the-highs-and-lows/

- Details of Veni winners, 17 September 2013 http://linkedup-project.eu/2013/09/17/veni-competition-winners/

- LinkedUp Use Cases http://linkedup-challenge.org/usecases.html

- LinkedUp Dataset Catalog (or Linked Education Cloud) http://data.linkededucation.org/linkedup/catalog/

- Datahub http://datahub.io/

- LinkedUp Devtalk blog,http://data.linkededucation.org/linkedup/devtalk/

- LinkedUp events and presentations http://linkedup-project.eu/events/ and

http://linkedup-project.eu/resources/presentations/ - Open Education Working Group http://education.okfn.org

- W3C Open Linked Education Community Group http://www.w3.org/community/opened/

- Open Education panel session, 17 September 2013

http://linkedup-project.eu/2013/09/17/open-education-panel-session/ - Open Education Booksprint, 3 September 2013

http://linkedup-project.eu/2013/09/04/open-education-handbook-booksprint/ - Booksprint.net http://www.booksprints.net/